Goodloe Byron, who is not to be confused with the late Congressman, is a kind and excitable gentleman who permitted me to use a corner of his table to hawk Bat Segundo CDs at last year’s Independent and Small Press Book Fair. He is the author of The Abstract, a self-published book that he has released without a dollar value into the world. (He informs me that he is sitting on numerous copies of his book in his barn.) But he is also a big fan of Knut Hamsun and, as it turns out, Jose Saramago. What follows is an essay in which Mr. Byron has presented his thoughts on the latter.

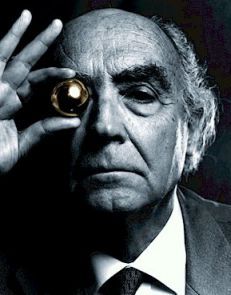

The Portuguese writer Jose Saramago describes humanity with the same alien fascination with which the Belgian naturalist Maurice Maeterlinck used to describe insects. This foreign view of civilization is entirely appropriate, as Saramago looks less like a man than a Methuselahan turtle, peering around with a goggly apparatus strapped to his temple.

The Portuguese writer Jose Saramago describes humanity with the same alien fascination with which the Belgian naturalist Maurice Maeterlinck used to describe insects. This foreign view of civilization is entirely appropriate, as Saramago looks less like a man than a Methuselahan turtle, peering around with a goggly apparatus strapped to his temple.

In Saramago’s view, the world is not balancing on a precarious pin, but is pinned to the floor by violence and power. Suddenly, the impossible becomes possible: Blindness comes to replace selective attention with something that no longer selects anything; private regret transforms into public lucidity in Seeing. In The Cave, the Vegas/Wal-Mart/Condominium/uber-complex called The Center, a simulacra of Plato’s Cave, is built atop a buried allegorical site which realizes the simile as a literal state of being. But in these novels, society also accommodates the intruding impossibility: the blind are quarantined in dark cells; lucidity is diffused by propaganda, and the cave is turned into a spectacle itself. Since Blindness, Saramago’s seemingly impossible inspirations have become finely attuned Chestertonian paradoxes, and these situations, in turn, break the smooth surface of reality, exposing the tender and often stupid mess underneath. He’s studying the human being by injecting our world with an unstable but vivid isotope.

Saramago’s latest experiment has finally arrived in the United States. Death with Interruptions is about a country where people stop dying. This is not a book of wishful thinking. Death is such a pivotal structural entity in our world that any attempt to carry out our experience without it would transform it into an absurd character; insurance companies introduce a “working” death at the age of eighty four, funeral directors petition to transfer the commodities of mourning to pets and parakeets. These may seem satirical, but these exigencies are as real as the subsidies creating grain surpluses which are subsequently burned. Counterbalancing this bureaucratic response is a terrible self-honesty that would necessarily follow; our sympathy for the elderly and the infirm is not empathy. It is only because the predator of death is out somewhere ready to strike that we can rally ourselves and attempt to stave it off. Saramago pictures this dilemma as if these marked souls will linger here forever. They are not in danger; we cannot save them. Suddenly these regular tasks define a new unromantic role: the custodian of the all but dead. Knowing that their condition can only get so much worse, I personally suspect it would be tempting to place the person in a storage locker and go to Atlantic City, but maybe this admission will jeopardize my babysitting career.

Not many of us are violent or wish death on others, but we all know that a steady stream of blood turns the mill. The mill is not turning here, but the poor are saddled with the financial burden of the permanently dying. With compassion for the ethical havoc that this would wreak on us, Saramago indicates the brutal solution at which we would certainly arrive; if no one had to die, these people would be required to die.

But thankfully, death returns! She is classically personified, coming to us with skull, scythe, and all, a contrast to the modern view of death as a biological process. Now the story happens again, localized to a single character: an unsung cellist whom death is unable to kill. Suddenly, the story focuses and takes on the tone of an old school romance, and interestingly shares some traits with romantic obsession narratives such as Marc Behm’s Eye of the Beholder. It is a Da Capo al Fine move, repeating the central premise of the book but altering environmental physics from the purely positive world of his later phase, into the classical fables that characterized his first. Though something along this lines was hinted at in Seeing, to my mind, this is a transition radical enough to be considered entirely new for Saramago, and it presents us with the skeleton key to the book. This time, Death is amazed by her own impotence in the face of the human being, who remains ignorant of her, a nice reversal of the working order. This goes to the core of what Saramago’s all about, recalling the distinction between the human will (the mortal, individual spirit that dies with or before us) and soul (the eternal part of man removed from its human excess) that he explored in Baltasar and Blimunda. Instead of judging humanity by what is naturally effective (a la Deng Xiaoping), Saramago is suggesting that we should judge nature by what is morally affective (which, for Saramago, is grassroots Marxism).

Lastly if I may please note: English speakers are very lucky that Saramago’s phase shift, with the arguable exception of Blindness, has been so well-amplified in the opposed translation styles of Giovanni Pontiero and Margret Jull Costa. Obviously this distinction is a bit twisted, as this good fortune has come with the expense of Mr. Pontiero’s untimely demise. Whereas Mr. Pontiero’s style appears to radiate with a formal erudition, in the service of the most exact representation possible, Ms. Costa’s weapon of choice appears to be her imagination, in which she welds with her efforts to preserve the overall style and impression of the book. This is further evidenced by her chameleonic translations of Eca de Quieroz. As a person who can only read one language, I acknowledge being a bit of a straw man on this topic. That she would be trying to single-handedly import a neglected culture into English would be commendable as a doomed enterprise, and that she appears to be succeeding at it (and perhaps this is an area where appearing to succeed is all success really is) is awesome.

Saramago doesn’t show any sign that he will rest on his laurels, nor would anyone familiar with his work expect that he would be the sort of person to consider such a thing to be a worthwhile activity. Not long ago he completed his newest book The Elephants Journey, so now Saramagoons such as myself will have something to wait for.

The Portuguese writer Jose Saramago describes humanity with the same alien fascination with which the Belgian naturalist Maurice Maeterlinck used to describe insects. This foreign view of civilization is entirely appropriate, as Saramago looks less like a man than a Methuselahan turtle, peering around with a goggly apparatus strapped to his temple.

The Portuguese writer Jose Saramago describes humanity with the same alien fascination with which the Belgian naturalist Maurice Maeterlinck used to describe insects. This foreign view of civilization is entirely appropriate, as Saramago looks less like a man than a Methuselahan turtle, peering around with a goggly apparatus strapped to his temple.

I had a bad day last Friday, a day

I had a bad day last Friday, a day