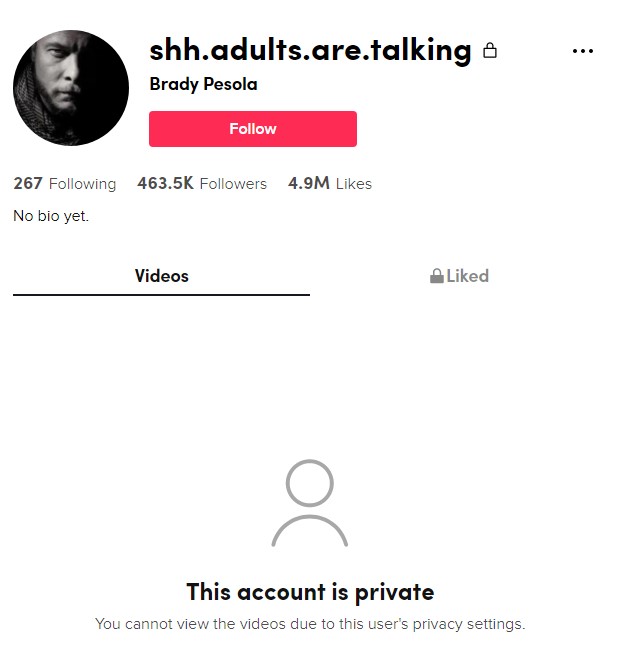

This morning, I learned that my TikTok account was permanently banned. Why? Because I spoke out against the misogynistic TikTok user Brady Pesola, who goes by the handle @shh.adults.are.talking.

Pesola specializes in a type of repugnant hypermasculine sexism that has netted him nearly half a million followers. His ugly formula of speaking in a tenth-rate John Wayne swagger and casually demeaning women for their feelings and their thoughts has proven such an alluring draw that he has been able to parlay this into a sizable fan base. I had responded to one of Pesola’s slightly less sexist posts in which he boomed, “Stop being an insecure little bitch and grow up,” by pointing out, quite calmly, that being emotional was not a sign of insecurity. For this, Pesola singled me out as “unhinged,” prefacing his stitch by saying “This one’s extra spicy.”

I was then bombarded by numerous comments from Pesola’s followers and later had my account hit with false reports of bullying and harassment, after I proceeded to outline the full extent of Pesola’s misogyny in a series of videos. And I received a permanent ban. I have tried to appeal this ban, but I have heard nothing from TikTok. The message is clear. TikTok supports the misogyny of creators with huge followings rather than the small-time people who speak out against such vile strains. I also suspect that I was targeted by TikTok because a few of my anti-corporate and pro-union videos went viral. Since I cannot access my videos, this article represents a thorough effort to expose and document Pesola’s clear hatred of women, as well as TikTok’s willful advocacy of misogyny among its high-ranked creators, despite community guidelines declaring that hateful behavior directed towards a group is prohibited. A thorough review of Pesola’s TikTok feed reveals that he violated these rules multiple times and faced no consequences — aside from a 24 hour ban in December 2020 and a permanent ban for twenty minutes that was somehow removed this month. Apparently, if you have enough followers on TikTok, you can get away with saying anything. The rules don’t apply to those who have the clout.

Pesola, a former Marine based in the San Diego area (originally from Minnesota) who runs a dubious nonprofit operation known as the Gray Man Project with some shady emphasis on self-reliance (a public records search and a Guidestar dive reveals no record), published his first TikTok on October 11, 2020. He has claimed to be a private investigator. A search with the California Department of Affairs reveals that he is licensed (with a firearms permit) through October 31, 2022. Pesola’s license matches up with an operation called The People’s Detective, which claims to be “a full-service investigative agency with a 30-year track record of successful investigations, high profile cases, and newsworthy discoveries.” (The People’s Detective did not return my requests for comment.)

Pesola’s initial four videos detailed how a Sharpie, a flashlight, and a belt could be used to attack someone and his initial videos shortly after this quartet were carried out with a strain of tough-talking military bravado and alleged expertise. This was apparently enough for Pesola to earn the beginnings of a following, where his relationship to his audience would involve addressing douchebags (while mispronouncing Epictetus, whom he has frequently declared to be his favorite philosopher) and engaging in fairly unimaginative conservative talking points.

As Pesola acquired more of an audience, it took only days for Pesola to go off the deep end with an October 14, 2020 video in which he declared, “Toxic masculinity is a myth…Masculinity is a heightened state of being that all men should strive for.” By October 23, 2020, Pesola began honing the beginnings of his pugnacious TikTok formula, calling some of his audience “motherfuckers” and “miserable pricks.” But this was enough for Pesola to gain 11,000 followers in two weeks. Pesola then started stylizing his voice in a preposterously deep manner to woo more followers. At this point, the strains of misogyny and ugliness that were to become Pesola’s hallmarks still drifted somewhat in the background. But since this was his chief draw, it became more of his raison when publishing videos.

In an October 20, 2020 video, Pesola offered hotel advice, claiming that you didn’t want to get a hotel room on the second floor because there might be “some fucking crackhead breaking in the window and wanting to get in bed with you in the middle of the night. Unless you’re into that.” He called peaceful protesters “fucking retards.” By the end of October 2020, Pesola gradually strayed away from his tips on security and began embracing the beginning of his bullying, going after the “ignorant fucking retards.” He reveled in crude violence when offering “advice” to domestic violence survivors, suggesting that women “turn into the most vicious, fucking, violent psychopath you can imagine in your entire life.” While dispensing questionable wisdom to rape survivors, Pesola giddily declared, “Guys will fuck you with a potato sack and heels on.”

By November 2020, Pesola’s feed had become a reliable hotbed of hideous misogynistic takes. He bemoaned the idea of men facing penalties for hitting a woman while adopting a phony position against domestic violence. (Pesola spent most of his time in this video siding with men who were simply “defending” themselves, concluding in a crude manner, “I don’t care how good the pussy is. Get away from that toxic shit.”) In a November 11, 2020 video viewed by 912,600 people, Pesola reached his first major viral nadir of casual misogyny, claiming that preventing rape was the responsibility of women and that it was a woman’s obligation to parent well: “I got an idea. Be better fucking mothers.” When, on November 28, 2020, a TikTok user named @gishaz called Pesola out on the misogyny of this post, Pesola smugly responded, “So you agree then that the world does need better mothers.”

It took six weeks for Pesola to hit 100,000 followers. And by early December 2020, the fame had swelled to Pesola’s head. He confidently announced, “Hello ladies. I know what makes you tick.” In a multipart series that began on December 6, 2020, Pesola giddily described how he manipulated an escort into almost having sex with him for free, later bragging about lying to this escort by claiming to be an escort, and offering further confabulations that he couldn’t enter into a meaningful relationship because of his false escort role. For Pesola, women are merely sexual vessels to be used — with counterfeit empathy as the tool.

By December 22, 2020, Pesola was referring to himself as a “famous TikTokker” and, with his colossal hubris confirmed by his growing follower base, he declared on Christmas Eve, “Frankly, I don’t give a fuck if I’m likable. Apparently, 160,000 followers is telling me [sic] that I’m doing something right.” And there was more sexism to come: Pesola remarked on the unfairness of men paying child support, offered tips on how to keylog a lover’s phone, claimed that there was no such thing as rape culture (“It’s illogical and just plain fucking stupid.”), reconfirmed his view that toxic masculinity was a myth, and took the side of a man in a marriage split without considering the woman’s perspective (“It sounds like his ex-wife is a righteous cunt.”). By the turn of the year, Pesola had become hopelessly resolute in his hatred of women. When not condemning Nelson Mandela, he claimed that a man giving his phone to his girlfriend was weak (“Oh boy! That’s a red flag towards an unhealthy and toxic relationship.”), demeaned women for not revolving their entire lives around men (“If she doesn’t value your time as her man, then she’s always going to be a waste of time as your woman.”), and condemned women for allowing men to be disrespected.

On November 19, 2020, Pesola risibly claimed that it was important to treat people with different perspectives and worldviews with respect. It was advice that he was not to follow months later when he started using his bully pulpit to crush any position that differed from his own. He started addressing his audience as “fuckfaces” in late January. He engaged in casual fat-shaming with a disturbing eugenics streak, demanded that women make more money as they aged (“Your looks depreciate as you get older.”), claimed that blowjobs were the male equivalent to a woman receiving flowers, claimed that anyone who was offended by behavior was a “stupid fuck,” and falsely claimed that the government was forcing people to get vaccinated.

Pesola did not reply to my questions. But the undeniable strain of misogyny in Pesola’s TikTok feed is clearly the very quality that the TikTok algorithm values the most. This allowed an unremarkable chowderhead in Carlsbad with a toxic strain of sexism to become a small-time TikTok star. Systemic misogyny appears to be permanently baked into the factors that cause TikTok videos to end up on the For You Page. And if you speak out against this nefarious truth, you get banned. In my case, I made hundreds of largely benign videos on TikTok. I offered empathy to people who looked like they were in trouble. I sang songs. I cracked jokes. But none of that matters. Because I dared to speak out against a garden variety thug like Pesola, all that I made is now inaccessible to me. I have no backup copies. Pesola, on the other hand, will be just fine. And it is because Pesola perceives women as little more than shallow little wretches to manipulate. Despite the significant advances of the #metoo movement, hating women is apparently still your hot ticket to social media fame.

5/28/21 UPDATE: Deputy Daniel “Duke” Trujillo is now dead of COVID. This Denver deputy did not have to die. He could have received his vaccination. But as the Twitter user @RacistProgramming reported, Trujillo was heavily influenced by one of Pesola’s anti-vaxx videos.

Denver Sheriff Deputy Duke Trujillo died from COVID-19.

Trujillo posted an anti-vaccine video and pics to his Facebook. https://t.co/okWwzUXSfl pic.twitter.com/LIYfhkcnGG

— Resist Programming 🛰 (@RzstProgramming) May 28, 2021

As of the morning of May 28, 2001, Pesola has also made his TikTok account private:

5/30/21 UPDATE: Faced with intense scrutiny from appalled users, Pesola has deleted all of his social media accounts, including TikTok and Twitter.

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones.

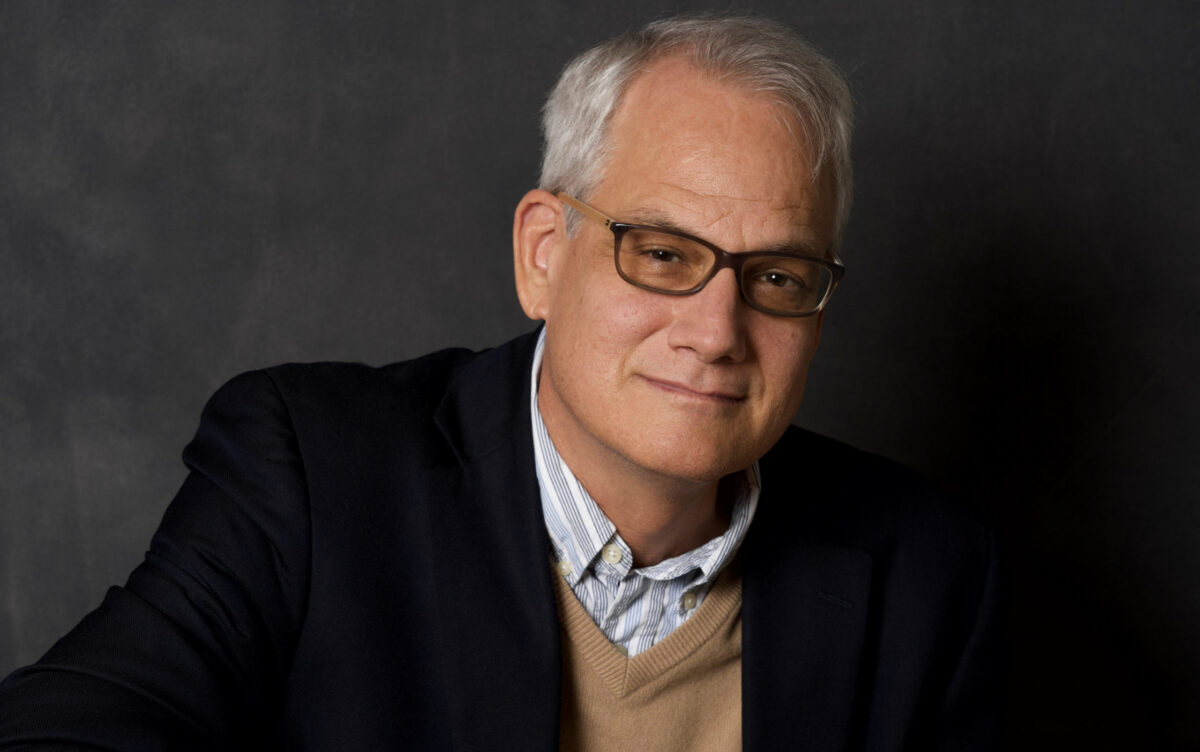

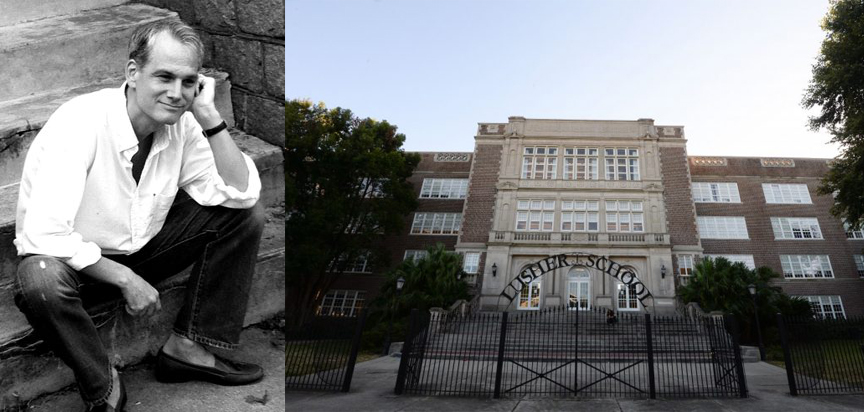

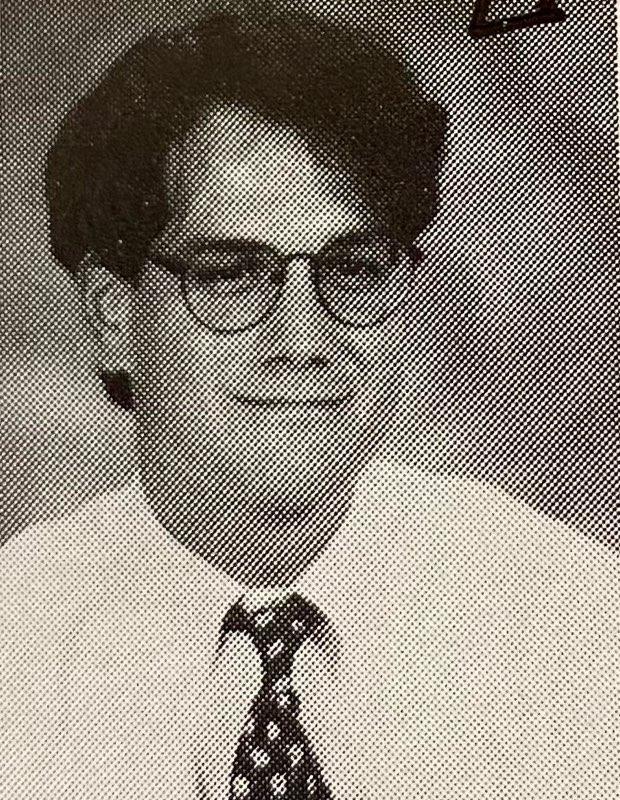

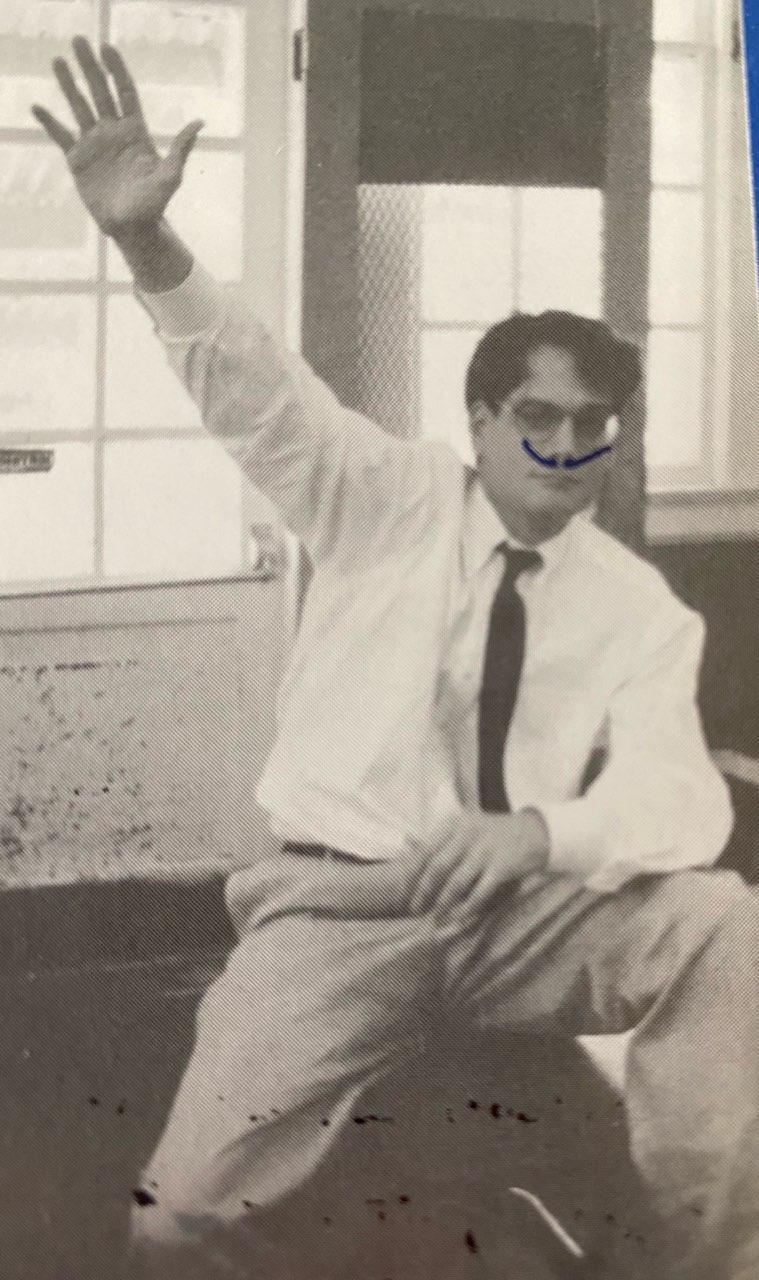

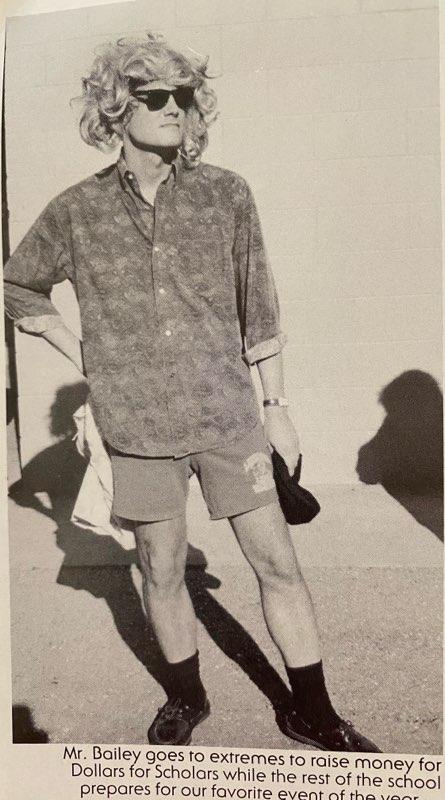

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones. This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.

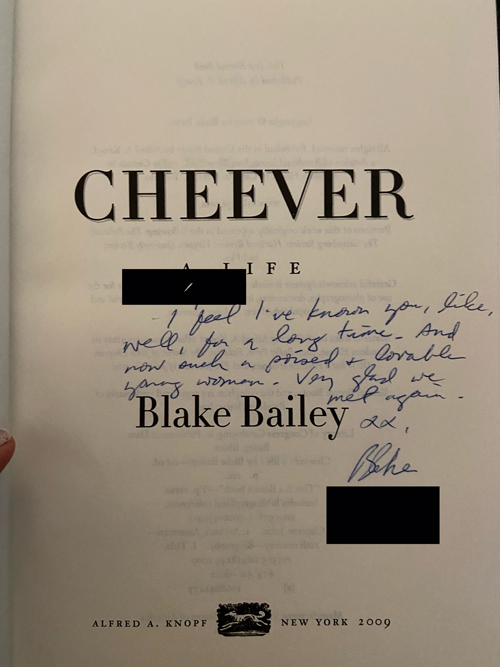

This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.  He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves.

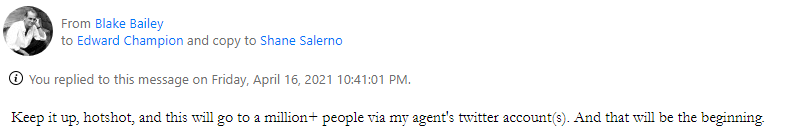

He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves. Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”

Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”