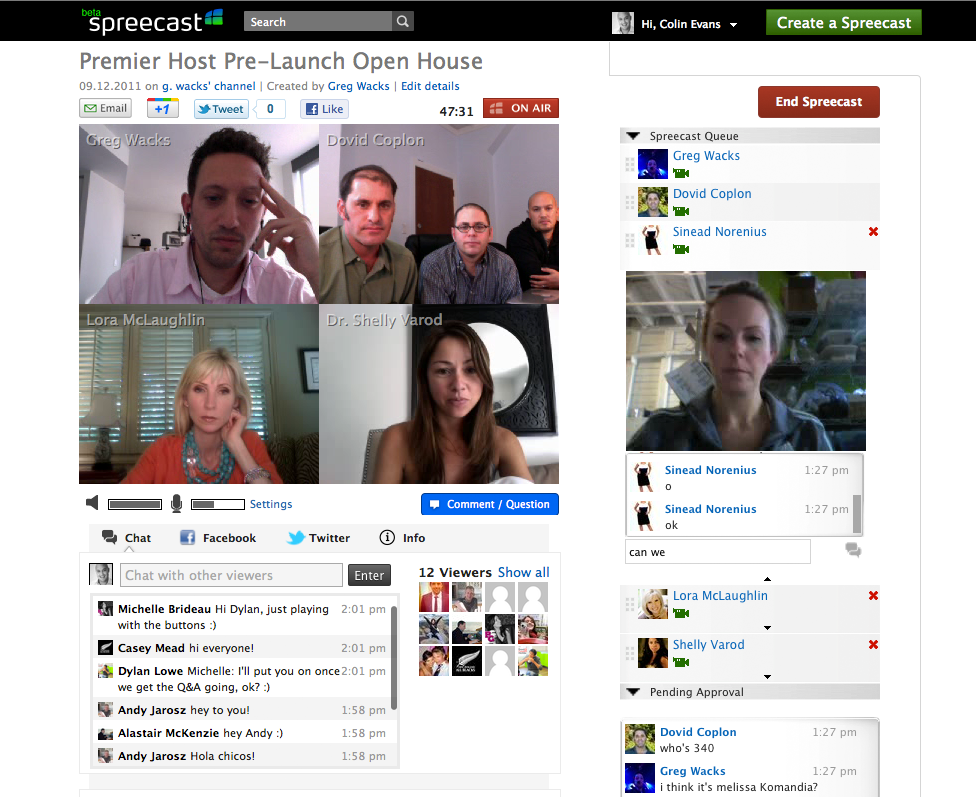

Spreecast was supposed to be the perfect social video platform. Launched as a public beta in November 10, 2011, it did not care if you signed in through Facebook or Twitter. It had raised $4 million in seed money from the likes of Viacom’s former CEO Frank Biondi and The Capital Research Group’s Gordon Crawford. In September, it found $7 million more. Young alternative poets and romantic entrepreneurs saw Spreecast making hard waves in the vast online ocean of multiuser possibilities. With the man who sold Stubhub to eBay for $310 million at the helm, what could go wrong? The videos you made would always be there. They’d have to be, wouldn’t they?

But this week, an untold number of content creators discovered that most of their videos had disappeared. They had toiled long hours to prepare for their shows. They had made new friends. And now every trace of those bright burning months had dried up in the heat of negligence.

“I think I was one of the first people to find out,” said Logistic Viewpoints‘s Adrian Gonzalez. “I submitted a customer service ticket Tuesday morning when I noticed that my video wasn’t accessible.”

On Wednesday night, Spreecast sent a mass email to some of its users:

This is Jeff Fluhr, CEO of Spreecast. I am deeply sorry to deliver this news. Recently, Spreecast made an internal error and your video files were mistakenly deleted. You will not be able to play your spreecasts created before Thursday, November 22, 2012.

Through one remarkable act of technical incompetence, Spreecast permanently destroyed countless videos from its users. It was an accident not altogether different from Caesar’s infamous stratagem against Achillas.

Historical precedent aside, why would a company with $7 million in Series A Funding not have basic data security measures in place from the beginning? While Fluhr told his users that “we have taken steps to ensure that this never happens again,” including correcting Amazon server settings and improving disaster recovery plans, he hasn’t said anything about how or why such a rookie mistake could go down on his seemingly experienced watch. Maybe the the truth is too embarrassing.

I left multiple voicemails with Fluhr and Spreecast representatives. None of them were returned. However, a public relations assistant named Nicole Brunet wrote back. “Yes,” she said, “an error was made and some video files were accidentally deleted. We thought we had backups, but it was not working properly. This is a very unfortunate situation and we are truly sorry. We have taken steps to ensure that this doesn’t happen in the future.”

But why wasn’t the backup system tested? How could a highly fallible system remain running for so long? Why wasn’t there a way for users to download their videos?

Brunet did not return my calls or followup emails.

Earlier in the year, Spreecast was quite eager to talk with people and get them to use their service. I spoke by telephone with Jenifer Daniels, a communications strategist based in Charlotte, North Carolina. She had been courted by Spreecast reps at a conference. Daniels was looking for a way to get together with people more frequently than twice a year. Three to four weeks after her meeting with Spreecast, Daniels started Ask a Sista, a Spreecast which gave African-American women an opportunity to discuss politics, pop culture, and scholarship.

“In some weird way, we were both upstarts,” said Daniels. “We both knew that we were taking a chance.”

Still, Daniels believes that the Spreecast boosters were sincere. The idea was to take Ask a Sista to a bigger platform. Yet because there were so many producers on the show, she had not received Fluhr’s automated message.

“I was trying to explain this to my husband,” said Daniels. “How would you feel if you showed up to work and the last four years that you’ve been there had been erased?”

Daniels says that the decision to place her faith in Spreecast was made more on emotion. But the intent was always to take her efforts to a bigger platform.

For Stephen McDowell and Josh Spillker, proprietors of I Am Alt Lit, Spreecast represented an opportunity to have fun and mimic the success of a friend. McDowell and Spillker used the service to host the literary interview show, I Am Alt Lit Confidential. But on Thursday morning, the duo posted Fluhr’s notice on their supplemental Tumblr, I Am Not Alt Lit, along with the following sentiments:

there’s some type of feeling in my body right now, mebbe like a ‘sinking’ feeling ???

those were ‘good’ times

remember when noah ‘cancelled’ the spreecastx and ‘typed’ everything ???

remember when we had that ‘non-rapper’ on ???

remember when you found out who I AM ALT LIT ‘rlly’ was and then immediately didn’t ‘care’ anymore ???

“When I initially thought of a live, video interview series,” wrote Spilker by email, “I had thought about recording a Google hangout or a Skype conversation, and then uploading the file to YouTube. But the interactive part was key to the community. It does seem more difficult to share Spreecast videos than YouTube, but I just thought that would be part of the growing company.”

“A friend of mine named Steve Roggenbuck, who’s a poet and has kind of gained a lot of underground literary clout, started doing a Spreecast,” said McDowell by telephone on Thursday afternoon. “Illuminanti Power Hour. It was regular, a large amount of hits.” (Roggenbuck did not return our requests for comment through email and Facebook.) [SEE 11/30 UPDATE BELOW.]

“It seemed like a natural place,” said Spilker, who pointed to other literary readings and groups on Spreecast such as Daniel Alexander’s efforts. “The only other service I was familiar with was Ustream, but I had not used it extensively. I guess we should have explored a couple of other services as well.”

“I don’t know who specifically is responsible,” said McDowell. “Generally I don’t put a lot of emotional energy into expecting things that happen on the Internet to be retained for long.”

But even before this week’s disaster, McDowell did consider the need to backup his shows sometime around early November, just before his program took a brief hiatus. He made efforts to download the raw files directly through Spreecast, but there was no clear button or link available. He figured that at some point his work could be downloaded, but soon began to realize that this was impossible.

“I just have a Flash file downloading app on my browser,” said McDowell. “I was checking to see if that worked.” While the app allowed McDowell to download YouTube and Hulu videos, Spreecast had erected an intermediary interface which didn’t provide access to the Flash files on its site. Yet while McDowell says he doesn’t “feel any immediate disdain or antipathy” towards Spreecast, figuring that any emerging streaming startup is likely to go through a few scrapes, he does feel “a mild sense of loss because I did enjoy doing the shows.”

But as of late Thursday afternoon, Spreecast still hasn’t explained in detail what went wrong.

“Spreecast needs to disclose more information about what happened,” said Gonzalez, “because considering the background and experience of the team there, I find it impossible to believe.”

“It is horrific,” says a filmmaker who asked to stay anonymous. “I am completely shattered about it. My audience can never go back and watch those sessions ever again.” This filmmaker’s videos were not backed up. During a phone call with Spreecast, a representative told her that they were working on a backup feature, but that it would only be available to premium (that is, paying) customers. “Mistakes happen, but I have no clue how something of this catastrophic level can occur.”

And while Daniels says that she’s not upset enough to threaten a lawsuit, she did tell me that she’s inflexible on at least one point.

“I’ll never do a show on there again.”

11/30 7:00 AM UPDATE: This story previously reported that Roggenbuck “declined to comment” about Spreecast, because one of our sources informed us that he wasn’t sure if Roggenbuck was interested in commenting. We should have written “did not return our requests for comment” and apologize for creating that impression. As it turns out, Roggenbuck did contact us on Thursday night through Facebook, telling us that he had been in touch with a man named Greg Wacks at Spreecast. Wacks claimed to Roggenbuck that one of the engineers screwed up a line of code and that many of the Spreecast archives were deleted and that there are “changes to make sure this doesn’t happen again.” Roggenbuck elaborated on his enthusiasm for Spreecast: “i know their intentions are the best and really i love their product for 95% of things, so im willing to roll with the bugs. they are doing awesome stiff i havent seen from any similar service.” I will make efforts to get in touch with Wacks to corroborate this story.

11/30 9:45 AM UPDATE: Greg Wacks contacted me by email on Friday morning. He directed me back to Spreecast’s Nicole Brunet, who, of course, has failed to answer any of my questions in depth. Wacks has not yet corroborated his telephone call with Roggenbuck. He has also not yet offered any clarity on the issue of Spreecast engineers screwing up a line of code, along with the lingering question of how a multimillion dollar company did not have greater safeguards for its data. It remains my hope that he will stop being opaque and answer the many questions I sent him, as this investigation has revealed quite significant insights into Spreecast’s relationship with its users and its failures to preserve and archive content that are difficult to ignore.

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling