Malcolm Gladwell‘s Blink isn’t as satisfying as The Tipping Point — in part, because Gladwell’s tendency to generalize is more prominent this time around. (Case in point: We’re supposed to marvel over John Gottman’s ability to determine if a married couple will still be together in fifteen years. Gottman can assess this with a 90% accuracy. Never mind that half of all divorces occur within the first seven years of marriage and that, depending upon what authority you consult, it is generally agreed that roughly half of all marriages end in divorce. An existing 50% probability weighed in with Gottman’s concentration on couples in their twenties — that is, divorces more inclined to occur, because younger people are more likely to divorce — and Gottman’s educated guesses leave a lot of wiggle room for the remaining 40%.)

Nevertheless, Gladwell’s interests in sociological and marketing casuism are always food for thought, particularly since he’s keen to serve up fascinating anecdotal examples. While he barely scratches the surface of “thin slicing” — the term Gladwell coins to describe what happens when someone uses latent subconscious impulses to serve up a quick judgment — he has got me thinking about how much of the publishing world is fixated on immediate judgment.

Terry Southern once remarked that, when he worked for Esquire, he could judge the quality of a manuscript based off of the first sentence. I’m wondering whether certain types of fiction are doomed because of the thin slicing editors have been applying to the slush pile. Was Richard Yates never published in the New Yorker because the editors trained themselves to react distastefully to Chekhovian naturalism? (Magical realism and postmodernism was very much the order of the day when Yates submitted his wares.) And just how much of this mentality is in place today?

(And I should point out that we’re all guilty of this. I don’t wish to inure myself. Recently, while reading its early pages, I was ready to damn Tricia Sullivan’s Maul based on what I perceived as tedious cross-cutting between the game going on in Meniscus’s mind and the cramped confines of a lab, until I gradually became aware of the subtle cultural allegory. Had I not kept reading after 100 pages, I would have probably have dismissed what turned out to be a daringly rugged novel.)

Further, if thin slicing is endemic to the book world, is this mentality what causes once popular authors like John P. Marquand (who made the covers of Time and Newsweek in 1949) to go out of print?

In one chapter, Gladwell uses the musician Kenna as an example for why certain forms of thin slicing aren’t always the best indicators. Kenna, who had earned nothing less than contagious kudos from such luminaries as Fred Durst and U2 manager Paul McGuinness (who flew him over to Ireland), along with repeated MTV2 airplay, built up such a sizable buzz that he packed a sizable crowd into the Roxy in less than 24 hours’ notice. But Gladwell notes that when Music Research did marketing, Kenna scored miserably and was thus unable to secure Top 40 radio airplay.

Gladwell suggests that Kenna’s failure with the number crunchers was because only certain forms of thin slicing works. Kenna’s music was not easily classifiable. Gladwell implies that some opinions are best formed over time and that corporations who are introducing products that are slightly foreign (such as the Aeron chair, another example that Gladwell uses) need time to be accepted (which may explain the repeated rejections that Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land received before becoming a cause celebre).

Since fiction is a form that often requires a careful reader to weigh in a story, it would be curious to know just how much of it is getting short shrift from today’s editors. The number of careless typos that one finds in today’s novels (that indeed manage to make it all the way to the paperback release) is often extraordinary, signaling a growing lack of regard for how a book is typeset and put together. But it may be even more alarming to consider how many of today’s experimentalists (say, the David Marksons or Gilbert Sorrentinos of our world) are more the victim of overtaxed thin slicers whose waning passions for the written word waltz hand-in-hand with the first impression gone horribly amiss.

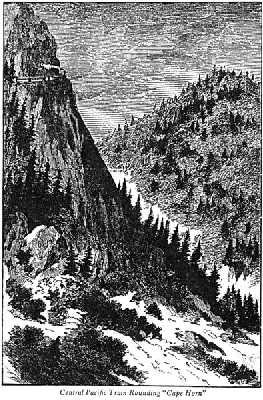

If you’ve ever made the drive to Reno or you’ve had the good fortune of riding today’s version of the Central Pacific Railroad, chances are you’re familiar with the Cape Horn grade. Near Colfax, the railroad juts upward and if you are fortunate enough to ride the railroad, one makes out a stunning view overlooking the American River.

If you’ve ever made the drive to Reno or you’ve had the good fortune of riding today’s version of the Central Pacific Railroad, chances are you’re familiar with the Cape Horn grade. Near Colfax, the railroad juts upward and if you are fortunate enough to ride the railroad, one makes out a stunning view overlooking the American River.