The Almanac’s staff has long wondered why Cinco de Mayo doesn’t get the proper respect it deserves. You see, a little more than a century and a half ago, 545 people died during the Battle of Puebla. The Mexican Army secured an unexpected victory against Napoleon’s forces, in large part because General Charles de Lorencez was arrogant enough to believe that the villagers would be sympathetic to the French military. Which is a bit like believing that a rape victim and her attacker will become BFF mere minutes after the brutal penetration.

545 dead bodies! Now that’s a death day to celebrate! But ask any fratboy guzzling down multitudinous margaritas about any of this, and he will intimate to you that Cinco de Mayo is the Mexican answer to St. Patrick’s Day. Then he will attempt to persuade you of his Hispanic roots (much as he attempted to persuade you of his Irish heritage only two months before), before swiftly abandoning the conversation (too intellectual, he may claim) so that he may scan the bar for a fetching mamacita before going home to an onanist’s bed.

Thus, Cinco de Mayo’s original celebratory purpose — founded upon war and death — has been transformed into a needlessly derivative holiday.

So it seems only fitting to celebrate the man who created and published Cliffs Notes — arguably the most derivative series of study guides ever printed. Yes, it’s the death day of Clifton Hillegass, who passed away nine years ago today on May 5, 2001. He died at his home in Lincoln, Nebraska. The cause: complications after a stroke.

So it seems only fitting to celebrate the man who created and published Cliffs Notes — arguably the most derivative series of study guides ever printed. Yes, it’s the death day of Clifton Hillegass, who passed away nine years ago today on May 5, 2001. He died at his home in Lincoln, Nebraska. The cause: complications after a stroke.

Hillegass published study guides which ensured that high school and college literature students were entitled to fake it, even if he didn’t quite believe that these were the reasons why young kids scarfed up his striped handbooks. Or did he? This seems a suspicious stance from a man who started off as an Army Air Corps meteorologist, a man who was accustomed in his early career to predicting things. But he profited quite well on American procrastination. In 1958, while managing a wholesale department, he founded his company in a basement with a $4,000 loan, starting by reprinting summaries of sixteen Shakespeare plays from a Toronto publisher. The publisher was a guy named Jack Cole. Why did the apostrophe in “Cliff’s Notes” disappear? Well, Hillegass broke off ties with Cole, striking it out on his own. Hence, the name “Cliffs Notes” — a suitably ungrammatical concession to the enterprise. In 1999, Hillegass sold his company to IDG for a cool $14 million.

Hillegass was described by one employee as “a very intellectual individual,” and enjoyed mysteries and and the classics. In a New York Times obituary, Hillegass’s daughter claimed that her father “just basically wanted to help them get as much out of their education as they could.”

The inside covers of these bright yellow guides include the sentence: “A thorough appreciation of literature allows no short cuts.” But when a bookstore customer asks for Angry Raisins instead of The Grapes of Wrath, as this overview reveals, one must consider the full extent of Hillegass’s complicity. In a 2007 interview, CliffsNotes shipping employee John Shank revealed that Hillegass (and consulting editor James L. Roberts) “were pretty comfortable that they were being used for what they were intended for, back in the 1950’s and early 1960’s.”

Or were they more comfortable with the company’s success? It’s difficult to say. Hillegass’s recent death has produced a great hagiographical response from the people who knew and worked with Cliff. But to be fair to Hillegass, perhaps he can’t be entirely blamed for those who preferred to avoid reading literature, any more than the fratboy can be blamed for forgetting the Mexican Army. An uncommitted student will remain without dedication to the task at hand, even when his sweaty palms rely on a yellow veneer that the teacher has already obtained. If it hadn’t been Hillegass, it would have been somebody else. And if the dipsomaniac wasn’t drawn to Cinco de Mayo, it would be some other occasion. (It’s just too bad that nobody thinks to get inebriated on Arbor Day.)

Stay writing, don’t die too early, and keep in touch!

It has been suggested by at least one prominent mortician that the Almanac’s staff has been dead for the past week. Well, the moribund undertaker in question was partially correct. Hans Campbell, our lead researcher, passed away on April 30, 2010, the victim of an unanticipated embolism experienced while putting together that day’s entry. He died at his desk — the way that any good researcher should. And it isn’t every day that you can claim to shake hands with a man who has the bad luck to die on the same day that Hitler blew his brains out (sixty-five years ago, if you’re as interested in the math as we are!). We here at the Almanac promise to not fuck around with a Walther PPK on a shooting range. We have given our small supply of cyanide tablets to a frenemy’s great aunt. So let the similarities between Hitler and Hans (or “HC,” as we nicknamed him in the office) end here. However, should anyone wish to make a Downfall video in HC’s honor, we suspect that his family will be greatly touched.

It has been suggested by at least one prominent mortician that the Almanac’s staff has been dead for the past week. Well, the moribund undertaker in question was partially correct. Hans Campbell, our lead researcher, passed away on April 30, 2010, the victim of an unanticipated embolism experienced while putting together that day’s entry. He died at his desk — the way that any good researcher should. And it isn’t every day that you can claim to shake hands with a man who has the bad luck to die on the same day that Hitler blew his brains out (sixty-five years ago, if you’re as interested in the math as we are!). We here at the Almanac promise to not fuck around with a Walther PPK on a shooting range. We have given our small supply of cyanide tablets to a frenemy’s great aunt. So let the similarities between Hitler and Hans (or “HC,” as we nicknamed him in the office) end here. However, should anyone wish to make a Downfall video in HC’s honor, we suspect that his family will be greatly touched.

It’s the death day of

It’s the death day of

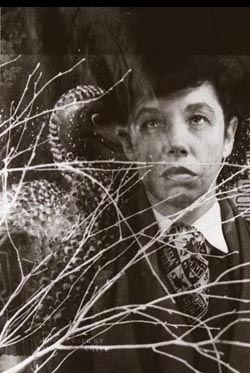

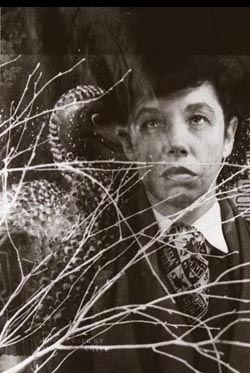

It’s the death day of Hart Crane, who passed away seventy-eight years ago on April 27, 1932. Hart Crane committed suicide. But it was a cheery suicide, as suicides go. Even if the consequences leading up to the suicide were bizarre and far from happy. You have to credit Crane for his courtesy in shouting “Goodbye, everybody!” to a crowd before throwing himself off a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico. I mean, how many of the hundreds of people who have thrown themselves off the Golden Gate Bridge have managed to even do that? The Dead Writer’s Almanac staff has conducted an informal poll, and it seems that people who shout “Goodbye, everybody!” just before leaping to their needless deaths are now considered exhibitionists who rely upon some crude cry for attention, the equivalent to that annoying guy at the party who complains about the lackluster canapes and the diminishing liquor supply. Suicide victims are now expected to leap to their deaths with a stoic resolve. No commentary. Just the self-immolation itself. But that seems needlessly limited when you’re a talented American poet.

It’s the death day of Hart Crane, who passed away seventy-eight years ago on April 27, 1932. Hart Crane committed suicide. But it was a cheery suicide, as suicides go. Even if the consequences leading up to the suicide were bizarre and far from happy. You have to credit Crane for his courtesy in shouting “Goodbye, everybody!” to a crowd before throwing himself off a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico. I mean, how many of the hundreds of people who have thrown themselves off the Golden Gate Bridge have managed to even do that? The Dead Writer’s Almanac staff has conducted an informal poll, and it seems that people who shout “Goodbye, everybody!” just before leaping to their needless deaths are now considered exhibitionists who rely upon some crude cry for attention, the equivalent to that annoying guy at the party who complains about the lackluster canapes and the diminishing liquor supply. Suicide victims are now expected to leap to their deaths with a stoic resolve. No commentary. Just the self-immolation itself. But that seems needlessly limited when you’re a talented American poet.