John Cleese is the purported author of the Declaration of Revocation, a missive directed at the people of the United States. With Cleese harboring possible ambitions to run as mayor of Santa Barbara, it’s very possible that Cleese may have momentarily merged his comedy with his politics. However, at present, there’s no conclusive evidence that Cleese wrote this. (via Tom)

Category / Politics

There’s Also This New Rap Thing That Causes Teenagers to Shoot Each Other Up in the Streets!

I don’t know who this Michelle Malkin person is. But her claim that emo is a soundboard for self-mutiliation is instantly deflated when she declares emo as “a new genre of music.” Jesus, I’m over 30 too. But even I’ve listened to Sunny Day Real Estate. It was the dirty white sheets that were cut into strips, not the flesh.

As for this “new genre of music,” I’ve got two words for you, Michelle: Ian MacKaye.

You know, in a court of law, you can’t file a complaint without stating a statute. Having a supporting argument is one of those nifty things that maintain due process and keep a good subject matter convincing. The ignorance with which these so-called “higher beings” dispense their wisdom amuses me. But I’m troubled by how many hangers on are duped by their faux punditry.

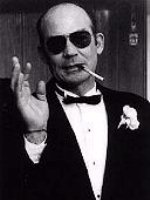

HST: The River is Still Running

I haven’t read the obituaries. I haven’t read anything. Hunter S. Thompson is gone and his unexpected suicide hit me hard. I was reduced to a blank, morose expression while sitting in a passenger seat in a moving car heading south for some fun. What fun could be had when America’s foremost nihilist and partygoer had decided that enough was enough? It took me about twenty minutes of explaining why Hunter S. Thompson was important and why his work mattered before I could go about my day.

I haven’t read the obituaries. I haven’t read anything. Hunter S. Thompson is gone and his unexpected suicide hit me hard. I was reduced to a blank, morose expression while sitting in a passenger seat in a moving car heading south for some fun. What fun could be had when America’s foremost nihilist and partygoer had decided that enough was enough? It took me about twenty minutes of explaining why Hunter S. Thompson was important and why his work mattered before I could go about my day.

Friends have often noted that I have an older man’s concern with the notable folks who die. But my concerns rest not with mortality, which is inevitable, but the more troubling question of enduring legacy. Who will replace these voices? What other tangible creative things die in the process?

Because Thompson, like all the others, was needed and irreplaceable. The landscape of American letters can never equal the strange mix of chaos and wisdom that Thompson threw into his work with inebriated gusto. It should be noted that Thompson repeatedly read the works of H.L. Mencken and the Book of Revelations in Gideon Bibles when holed up in hotels. Thompson was a man committed to a subjective form of journalism that he believed in with religious fervor, but he never lost sight of the number of the beast painted around Washington.

His work was as shoot-from-the-hip and as inconsistent as any prolific hack. His writings varied from incoherent screeds to astute examinations of American hypocrisy. But at his best (whch was often), he mattered. Thompson stood alone as a courageous voice, and he got people to listen.

A few years ago, Hunter S. Thompson stated repeatedly in interviews, “No one is more astonished than I am that I’m still alive.” I always chalked this up to the Good Doctor defiantly drinking Wild Turkey, imbibing drugs, firing guns into the night, blaring televisions and banging out political diatribes (even howling like a banshee on the commentary track for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), maintaining the same life that he had built his career upon. Here was a man who had openly settled for Clinton in his collection, Better than Sex, hoping that some spark of true progressivism would endure. Yet two years later, he was the only writer with the balls to eviscerate Nixon upon his death.

In his autumn years, Thompson had settled into a comfortable routine of writing a sports column for ESPN. He had recently married and was keeping busy. But no one can keep a good political junkie down. And it was no surprise when Thompson came out with high hopes for Kerry in Rolling Stone. His essay concluded:

We were angry and righteous in those days, and there were millions of us. We kicked two chief executives out of the White House because they were stupid warmongers. We conquered Lyndon Johnson and we stomped on Richard Nixon — which wise people said was impossible, but so what? It was fun. We were warriors then, and our tribe was strong like a river.

That river is still running. All we have to do is get out and vote, while it’s still legal, and we will wash those crooked warmongers out of the White House.

Thompson must have taken the results in November hard. Harder than anyone. For as much as any of us stupored around for days, feeling as if our last hopes were defeated when four more years of Bush were upon us, Thompson had to feel the pendulum swinging to the right more viscerally than any Poe character.

There’s the famous passage in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in which Thompson describes the death of 1960s idealism:

There was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda….You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning….

And that, I think, was the handle — that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting — on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave….

So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark — that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

I always figured Thompson had found a way to go on and accept the hard realities of a nation thumping to a reactionary beat. And maybe he did for a while.

But make no mistake: despite Thompson’s ultimate answer to the predicament, that river is still very much running. And Thompson’s work will endure. The question now is this: Who has the courage to pick up the slack?

No Reading Statistic Left Behind

South Florida Sun-Sentinel: “Gov. Jeb Bush wants to increase spending on reading by $43 million this year and make reading money a permanent part of Florida’s public school budget.”

Hey, Jeb, give $43 million to me and I’ll give you all the reading you need. And then some.

I don’t know what bothers me more: the notion that $43 million given to “reading” without a specific spending plan sounds more like the cocaine tab hidden within blockbuster movie budgets under the heading “accessories” or the idea that money would somehow translate into a new generation of enthused readers through a osmosis involving dinero.

But then these are the kind of silly impressions one forms when an article fails to point at the specifics, which can be found here. And if you read the fine print, it isn’t about the reading at all, but the scores. No wonder some kids aren’t so crazy about books.

What We Do Now

I was very interested to see that Melville House has assembled a collection entitled What We Do Now. The book is a collection of essay from assorted people: Steve Almond on getting tough, Maud Newton on tax law, and Greg Palast on voting fraud are just some of the interesting people who turn up. But what impresses me about the collection is how it’s collated several disparate responses in reaction to the current political clime. More importantly, with only a few hours left in 2004, flipping through the book has provoked me into thinking about the same subject. Because What We Do Now‘s very unity and provocative smorgasbord structure has had me thinking about what currently ails the Left. Dennis Loy Johnson and Valerie Merians may be able boosters on the publishing front, but it’s a pity that this approach can’t extend to the Left’s everyday actions.

It may seem an obvious point, but unity has eluded progressives of radical and centrist stripes over the past decade. The Left is either unwilling or unable to cast off its idealistic dregs, all too eager to engage in useless in-fighting over petty details. Instead of campaigning and pulling together for the pragmatic choice (i.e., the candidate or the goals that will get us closer to the marvelous possibilities of representative government), the Left is all too willing to quibble.

I can’t support Kerry because he’s part of the Democratic machine.

I’m for the death penalty. And while I agree with everything else the Green Party stands for, I can’t abide by that point.

These sentiments aren’t the problems of the people who express them, but the mark of an ideology that is inflexible and non-inclusive. Because the truth of the matter is that we need those centrists, if only to call us on our shit from time to time and perpetuate a unifying yet inclusive dialectic. They’d respect us more if we actually stood proudly on our two feet.

The problem isn’t one of politics, but confidence. We need an image, a mentality and a demonstrated series of actions that is confidently and uncompromisingly progressive, but that is simultaneously open to many political stripes.

Here in San Francisco, we had a series of political rallies in 2003. Before they escalated into a war against the police and fulfilled the psuedo-Kent State fantasies of priapic reactionaries, everyday Americans and their families went to these rallies in droves. I know. Because I was there and I talked with more than a few. Some of them had attended these rallies for the first time. And oh how they were disappointed! Let us not forget that before the rallies were driven by mob mentality, despite the insufferable pamphlet-slinging of pro-Palestine supporters and enraged Wobblies, the rallies were places that appealed to a meaty faction of everyday people. They brought people together and had the potential to be a forum for mobilization and a long-term commitment that could extend well into November.

Politiical demonstrations might make twentysomething Free Mumia supporters feel better, but I would argue that, so long as they adhere to a general message without a realistic effort to change government (and most of them do), they are useless. For some, the endless dirge of insensible rhetoric and uninformed opinions might boost egos. But that mentality belongs elsewhere: say, an Elks Lodge meeting. Until rallies are purged of their splinter opportunism and they appeal to the people at large, they will not have much use to anyone outside of cranks and militant nihilists.

This may not be what the Left wants to hear, but the unity problem is so hopelessly embedded that even populist poster boys like Michael Moore are incapable of flexibility. In an interview with Playboy, Moore described an early meeting with Howard Dean:

My wife and I went to meet him with the idea of supporting him. We brought our checkbook. But we weren’t in the room with him five minutes when we thought, Geez, this guy is kind of a prick. We didn’t write the check. I was not surprised the night of the Iowa caucus. He had spent the better part of two years in Iowa, letting people meet him. To meet him is to be turned off by him, so I wasn’t surprised that he lost. The concept of Dean was incredible. The movement behind him was a revolution. It was exciting to see, but Dean imploding was no surprise.

Well, if you ask me, Michael Moore’s kind of a prick for failing to identify politics as a business that involves the occasional tango with snakes for a long-term solution. Moore failed to use his base or his films to pull for John Kerry early in the year. While he quite wisely hit upon a winning formula to get a message out to the people (the mass medium of cinema), his inability to offer a game plan or even some scintilla of hope made his efforts useless.

Meanwhile, the Religious Right, having honed their organizational abilities through the so-called “Republican revolution” in ’94, have taken their battle directly to the American people. They have used a mobilized drive of bigotry and fear to convince the heartland that Bush is the man for the job. The unfortunate reality is that they wanted it more than we did.

The time has come for us to want it more than they do. We have two years of mobilization in store for the midterm elections in 2006. And we must never underestimate that our everyday actions, whether it involves a kind gesture, building up connections with political officials at the local and state levels, or our purchasing decisions, all contribute more effectively to winning than we can possibly measure.

We can be bold and accessible at the same time. The only thing stopping us is hopelessness, inaction, and giving up. And that’s silly. Because from where I’m sitting, we’re only just getting started.