In the latest edition of Emerald City, Matthew Cheney offers us “Literary Fiction for People Who Hate Literary Fiction.” Cheney writes, “A reader only interested in a narrow type of writing (hard SF, for instance) is not going to find much pleasure from any literary fiction, but a reader who is interested in experiencing new realities, strange visions, visceral horror, and supernatural events has plenty to choose from,” and proceeds to offer a helpful list of authors for those who’d like to experience some of these alternative visions.

I think, however, it goes without saying that there’s a similar stigma working in reverse. I’m talking about a certain type of literary person who simply will not pick up a book penned by Arturo Perez-Reverte, Octavia Butler, China Mieville, Rupert Thompson, Gene Wolfe or Donald Westlake, precisely because the book is categorized in the mystery or science fiction sections of the bookstore. Sure, the literary person will pick up Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and go nuts over it because it is categorized in the fiction section or in some sense crowned by the tastemakers as “literary,” little realizing that Philip K. Dick explored similar ethical questions about cloning in his 1968 novella, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” (later turned into Blade Runner), as did Kate Wilhelm in Where Late the Sweet Birds Sing and David Brin in Glory Season. The list goes on.

In fact, when we examine the rave reviews given to Ishiguro, we find a profound misunderstanding, if not an outright belittling, of science fiction:

Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times: “So subtle is Mr. Ishiguro’s depiction of this alternate world that it never feels like a cheesy set from ”The Twilight Zone,” but rather a warped but recognizable version of our own.”

Louis Menand, The New Yorker, on the book’s ending: “It’s a little Hollywood, and the elucidation is purchased at too high a price. The scene pushes the novel over into science fiction, and this is not, at heart, where it seems to want to be.”

Siddhartha Deb, The New Statesman: “This unusual premise, emerging through Kathy’s memories, does not lead us into the realm of speculative science fiction. Unlike Margaret Atwood in Oryx and Crake (2003), Ishiguro is not interested in using the idea of cloning to conjure up a panoramic dystopia.”

These all come from non-academic publications which might be considered “of value” to the literary enthusiast. And yet note the way that Kakutani is relieved that Ishiguro’s book doesn’t inhabit the realm of science fiction (indeed, failing to cite a specific science fiction book in her comparison). Or the way that Menand suggests that the novel’s ending is “pushed over into science fiction.” (Never mind that, by way of its story, Never Let You Go, with its premise of engineered clones, its near-future setting, and its shadowy governments, is indisputably a science fiction novel. So the idea that it would be pushed into a genre it already inhabits is absurd and contradictory.) Meanwhile Deb praises the novel’s “unusual premise” but, despite Ishiguro’s science fiction elements, it somehow does not fall into the redundant term of “speculative science fiction.”

What we have here is a strange reviewing climate transmitting a clear and resounding message to the literary enthusiasts who read the reviews. If a novel manages to convince a sophisticate or a literary enthusiast that it does not inhabit a genre, then it is, in fact, literature. If, however, there is a single experiential passage reminiscent of or explicitly describing bug-eyed monsters or aliens or clones, then sorry, but you’re taking a gritty stroll in the ghetto and you should be ashamed of yourself for taking off your evening gown and putting on some old sweats. Is this really so different from the backlash Dan Green recently identified against experimental fiction?

Of course, M. John Harrison, himself a fantastic science fiction writer, was one of the few to observe, “[Y]ou’re thrown back on the obvious explanation: the novel is about its own moral position on cloning. But that position has been visited before (one thinks immediately of Michael Marshall Smith’s savage 1996 offering, Spares). There’s nothing new here; there’s nothing all that startling; and there certainly isn’t anything to argue with.”

The fact that the literary climate refuses to examine, much less acknowledge, Ishiguro’s antecedents suggests not only that the genre stigma holds true, but that today’s reviewers operate with a deliberate myopia towards those authors who would innovate along similar lines in other genres. For the genre-snubbing literary enthusiast, there is something new in Ishiguro. The new realities, the visceral horror — all presented in a seemingly fresh way. But the very lack of inclusiveness in this approach is not only unfair, but critically unsound.

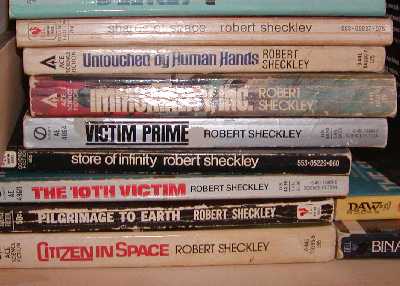

Before Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett (and perhaps Connie Willis), there was Robert Sheckley. Far from a mere wiseacre (although he was that and much more), Sheckley was one of the first authors to fuse satire with science fiction. Years before Stephen King ripped off the idea for The Running Man and decades before the crazed spate of reality television shows, Sheckley had written a short story, “The Seventh Victim,” in 1953, devising a futuristic world in which game show contestants were designated Hunters and Victims and competed for cash by murdering contestants. A film and a novel followed: The Tenth Victim (1965). Here is an excerpt that shows Sheckley in top goofball form:

Before Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett (and perhaps Connie Willis), there was Robert Sheckley. Far from a mere wiseacre (although he was that and much more), Sheckley was one of the first authors to fuse satire with science fiction. Years before Stephen King ripped off the idea for The Running Man and decades before the crazed spate of reality television shows, Sheckley had written a short story, “The Seventh Victim,” in 1953, devising a futuristic world in which game show contestants were designated Hunters and Victims and competed for cash by murdering contestants. A film and a novel followed: The Tenth Victim (1965). Here is an excerpt that shows Sheckley in top goofball form: