(2/25/2013 11:50 AM UPDATE: As Jim Romenesko reported, The Onion has issued an apology to Quvenzhané Wallis and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

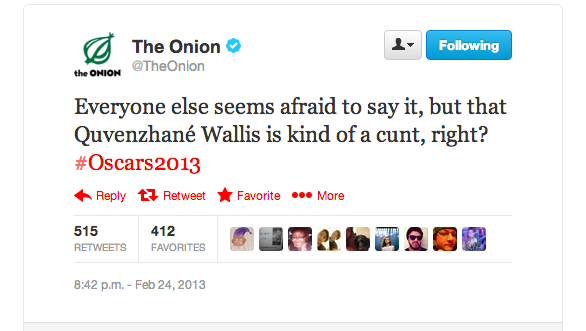

During last night’s Academy Awards, The Onion, a well-known satirical newspaper operating in Chicago, decided to row its barge into choppy waters. The Onion called Quvenzhane Wallis, a nine-year-old actress nominated for her performance in Beasts of the Southern Wild, a “cunt” on its Twitter feed:

In less than 140 characters, The Onion betrayed and violated 25 years of satirical good will. For unless you are a sociopath, there is nothing funny about calling a child a “cunt” — especially when there isn’t any additional context to the purported “joke.” It’s possible that the tweet was meant to mimic some of Academy Award host Seth MacFarlane’s misogynist misfires such as the insinuation that Wallis would be ready for George Clooney in sixteen years. Still, if one doesn’t apply a modest dose of narrative artistry, a joke falls dead in the moraine. And it was this vital part of comedy that was clearly ignored by the nameless person at The Onion who concocted the tweet. Because of this, the tweet became nothing less than thoughtless hatred, an act of bullying where a Twitter feed with a very large pull used its power (4.7 million followers) to attack someone verbally.

Here’s what the Onion failed to do: When Hustler published a fake Campari ad of Jerry Falwell on the inside front cover of its November 1983 issue, the descriptive details were reasonable enough to be considered fabricated and absurd. A fictitious interviewer asked a fictitious Falwell about his “first time” and the result was a clearly ridiculous incestuous affair in an outhouse. Falwell sued, but he wasn’t able to win. Because the humorist behind the parody performed the basic professional duty of supplying a narrative. And because of these vital details, all clearly wrong and all clearly part of a joke, Hustler won an unanimous verdict from the Supreme Court.

Until last night, The Onion had maintained a commendable comedy reputation with narratives along these lines, although The Onion had been pushing the envelope more in recent months. One reads, for example, this commentary from “Joe Hundley” — a piece that the Onion‘s defenders (nearly all of them male) offered to those appalled by the tweet. But the reader immediately understands the irony of professed victimhood behind the act. Unlike the tweet, it is not mere invective, although there is unpleasant language conveyed for the sake of verisimilitude. Nor are any of the supporting characters in the story real figures. Whether you find Joe Hundley’s commentary funny or not, the piece takes on the qualities of Hustler‘s Campari parody and is defensible.

The Onion‘s tweet was especially troubling because the newspaper courts a largely male demographic, with 48% of its readership making $75,000/year or more, and there is undeniably privilege when a newspaper with a largely white, male, and affluent audience with just under 5 million followers on its Twitter feed picks on an African-American girl who is the daughter of a teacher and a truck driver.

As of early Monday morning, the offending tweet had been deleted from The Onion‘s Twitter feed. There was no acknowledgment in the Onion‘s Twitter feed that the tweet had been deleted, and there was no apology on the Onion‘s Twitter feed or its website. But there was a lot of understandable bile.

Now I don’t wish to suggest that the word “cunt” be prohibited from public speech. However, those who elect to use it in public dialogue need to understand the implications of the word, especially when it is directed at children. There’s a world of difference between what The Onion did last night and how George Carlin’s famous routine used “cunt.” Carlin was careful to illustrate the meaning of “cunt” and six other words. He was not using it to insult people, although people were insulted by his demystification of “cunt.”

But if someone is going to use “cunt” for hateful purposes — and there is truly no other interpretation of the Onion‘s tweet, whether the hatred was intended or not — then the organization or individual which employs such usage needs to be held accountable. As Gawker‘s Camille Dodero exposed last week in horrific detail, bullies with a power base can make an innocent person’s life quite miserable. Could not the Onion tweet, ratcheted up by others with too much time on their hands, be used to similarly hurt Quvenzhane Wallis? We take the risk every time we send something out into the universe, but sometimes we need a bit of forethought.

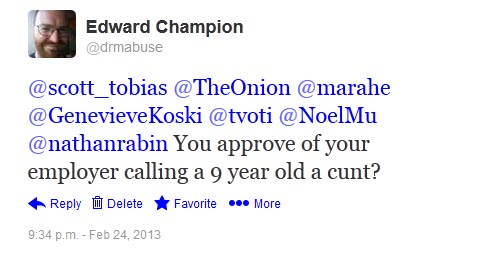

On Sunday evening, I put forth the proposition on Twitter that anyone who worked for The Onion and The A.V. Club, a print edition bundled with The Onion, should be held accountable for this tweet.

I called out members of The A.V. Club. Scott Tobias, film editor of The A.V. Club, claimed that because he and his writers do not write for the Twitter feed, they should neither consider the impact nor be held accountable for what their employer does. TV Editor Todd VanDerWerff, said that he “had literally nothing to do with the Onion.” I asked a point blank question to both Tobias and VandDerWerff:

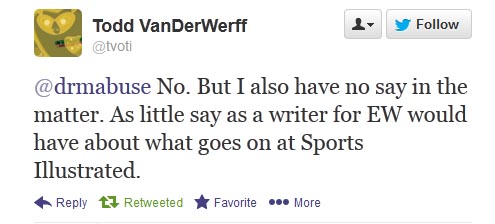

VanDerWerff replied with a fairly straightforward answer and explained that he has no regular contact with The Onion, which I thought at the time to be a fair and reasonable reply, until I checked his LinkedIn page and discovered this among his job duties:

Planned TV coverage with a freelance staff of several dozen. Editing that coverage. Wrote 10-15 pieces per week.

No contact with the Onion at all while managing several dozen freelancers? Really?

However, the other striking aspect about VanDerWerff’s reply is that he had the decency to offer a direct answer to my question.

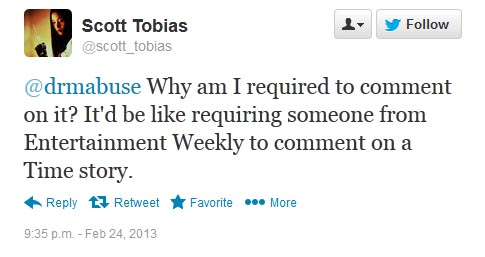

Tobias did not.

As a film editor, Tobias almost certainly coordinates with people who work at The Onion. But he suggests in this tweet that The A.V. Club, a print supplement that is bundled with The Onion not unlike a newspaper section, is a publication that is as discrete as a separate magazine. This is misleading. One does not typically get Entertainment Weekly folded into an issue of Time. Nor is The Onion on the level of Time Warner. Time Warner employs 32,000 people. It is believed that Onion, Inc. employs 70.

I pointed out to Tobias that he was quite obligated to the company that signed his paychecks. Unlike VanDerWerff, he could not put himself on the line and respond with a firm position. He finally did answer my question, but his response is quite telling.

So let’s break this down. Despite the fact that he works with people at The Onion, he is “not responsible.” In other words, Tobias has such lackadaisical journalistic standards that he could not care less about how the tone set by one part of The Onion (in this case, the Twitter feed) affects the section he edits.

Now it’s possible that I’m applying too much institutional value to The Onion‘s operation. But when I was on staff at a computer magazine, I learned very quickly the degree to which other editors and executives put pressure on you to adhere to the magazine’s standards and principles. As an articulated example of this, you can look no further than the very clear ethos adopted by The New York Times:

The company and its units believe beyond question that our staff shares the values these guidelines are intended to protect. Ordinarily, past differences of view over applying these values have been resolved amiably through discussion. The company has every reason to believe that such a pattern will continue. Nevertheless, the company views any intentional violation of these rules as a serious offense that may lead to disciplinary action, potentially including dismissal, subject to the terms of any applicable collective bargaining agreement.

Tobias doesn’t appear interested in such guidelines (if, indeed, any are in place), much less having a discussion about how an Onion staffer’s misogynistic breach might affect his operation. He’s “not responsible.” That’s how little he cares about The Onion and that’s how little he cares about the right tone.

As Laurie Penny argued in November 2011, “If we want to build a truly fair and vibrant community of political debate and social exchange, online and offline, it’s not enough to ignore harassment of women, LGBT people or people of colour who dare to have opinions.” And it’s this unthinking idea of “not taking responsibility” and not taking a stand that allows casual misogyny to perpetuate. It is Tobias’s refusal to address challenges and this need to get approval from the people who already like him which kill the dialogue.

I’d like to think that The Onion and Tobias were better than this. I’d like to believe that they have it within them to do some soul-searching on what this failed joke really means for the work they do. But as long as The Onion circles the wagons, they’ll remain part of the problem that won’t go away, no matter how much they try to ignore it.

2/25/2013 11:50 AM UPDATE: As Jim Romenesko reported, The Onion has issued an apology to Quvenzhané Wallis and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences:

No person should be subjected to such a senseless, humorless comment masquerading as satire.

The tweet was taken down within an hour of publication. We have instituted new and tighter Twitter procedures to ensure that this kind of mistake does not occur again.

In addition, we are taking immediate steps to discipline those individuals responsible.

Miss Wallis, you are young and talented and deserve better. All of us at The Onion are deeply sorry.