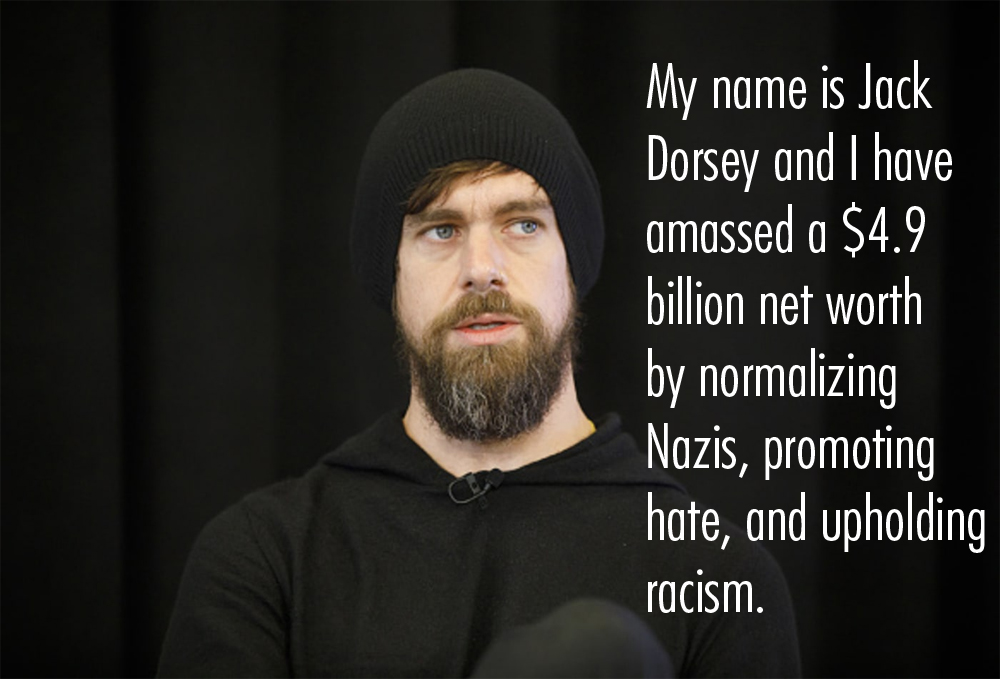

On Tuesday, Andrew Yang dropped out of the 2020 presidential race. He was only able to crack 2.8% of the vote during the New Hampshire primary and a mere 1% of the Iowa Caucus votes. But Yang’s presence represented an outlier sincerity that was sui generis, a welcome reminder that the Democratic frontrunner this year can possess a genuine empathy for the American people that can be worn on one’s sleeve without apology. Yang filled the void left by Beto O’Rourke’s exit with his off-kilter sincerity. He was an inspiring force for the “Yang Gang,” a group of supporters who were just as passionate as “Bernie bros” and justifiably excited to see an Asian American represented in a vital election race. He was the lone non-white regular on the debate stage after Kamala Harris, Julian Castro, and Cory Booker dropped out of the race. And after Bong Joon-ho swept the Oscars on Sunday with Parasite, it seems a great letdown to take in the dawning reality that Yang won’t be participating in future debates. In an age in which Jack Dorsey and his crew of idiots upholds racism and hateful xenophobia on Twitter through ineffectual algorithms incapable of parsing nuance and intent, we truly needed more voices like Andrew Yang to set the record straight on a very real disease that ails us.

Yes, Yang, with his lack of necktie and his MATH pin always clipped to his lapel, was socially awkward at times. During the third democratic debate, when Yang introduced a raffle where ten families would receive a “freedom dividend” of $1,000 each month for a year (he later expanded this to thirteen families), he was received with bafflement and modest ridicule. But this seems to me unfair. Unlike other millionaires who entered the race for ignoble and narcissistic reasons (**clearing throat** Bloomberg **spastic and theatrical coughing**), Yang really wanted to solve our national ills with wildly original ideas. He believed that he could cure systemic racism with his universal basic income concept, providing purchasing power to minorities. While this was a batty idea and while his tax policy was more concerned with implementing a value-added tax rather than addressing income inequality, there was nevertheless something appealingly immediate about his position. Was it really any less crazy than finding the essential money for Medicare for All or Elizabeth Warren’s plan to forgive $1.6 trillion of student debt? Yang smartly recognized that one of our long-standing national ills requires a swift remedy and that mere lip service — the empty and cluelessly myopic white privilege that one sees prominently with Pete Buttigieg — won’t cut it.

Yang also had a refreshing sense of humor about his campaign. He sang “Don’t You Forget About Me” at a campaign rally. He crowd surfed at another rally. He even skateboarded before an appearance. Andrew Yang brought an instinctive sense of fun that seemed beyond most of the other candidates, but his heart seemed to be in the right place. He never came across as wingnut as Marianne Williamson or as stiff as Tom Steyer or as cavalierly hostile to voters on the fence as Joe Biden. Even if you couldn’t see him as President, it was almost impossible not to like the guy.

Yang’s willingness to commit to positions of empathy and understanding in provocatively inclusive ways was one of his great strengths. Last September, when comedian Shane Gillis was hired by Saturday Night Live as a regular and fired after repugnantly racist remarks about Chinese Americans were discovered on YouTube, it was Yang who called for a dialogue and a second chance for Gillis. Yang remarked, “I thought that if I could set an example that we could forgive people, particularly in an instance where, in my mind, it was in comedic context or gray area, that I thought it would be positive.”

Yang didn’t really have the opportunity to display the full range of these subtleties. But we did get one moment during his final debate when he calmly responded to Buttigieg shallowly grandstanding about the collective exhaustion of people outside Washington: “Pete, fundamentally, you are missing the question of Donald Trump’s victory. Donald Trump is not the cause of all of our problems. And we’re making a mistake when we act like he is. He is the symptom of a disease that has been building up in our communities for years and decades. And it is our job to get to the harder work of curing the disease. Most Americans feel like the political parties have been playing ‘You lose, I lose, You lose, I lose’ for years. And do you know who’s been losing this entire time? We have. Our communities have. Our communities’ way of life has been disintegrating beneath our feet.”

While there’s certainly a very strong argument that present frontrunner Bernie Sanders has united variegated people by highlighting their stories, Yang had a way, unlike the other candidates, of going directly to the underlying heart of aggravated Americans in the heartland who altered their votes in the 2016 election after being fed up after years of condescending vacuity. It is them who the Democratic candidate must speak to. Yang’s inclusive approach to empathy seems well beyond Buttigieg’s platitudes, but it appears to be increasingly adopted by Amy Klobuchar (which partially accounts for her third place win in New Hampshire).

Andrew Yang opened up a promising road for people of color to speak to voters who are still knowingly or unknowingly practicing systemic racism. And for this not insignificant contribution, he’ll have a place in my heart. America may not have been ready in 2020 for Yang’s approach to empathy, forgiveness, understanding, and inclusiveness. But this nation will almost certainly be prepared for this in future presidential elections. It will take some time, but I think history will see that Yang was ahead of the curve.

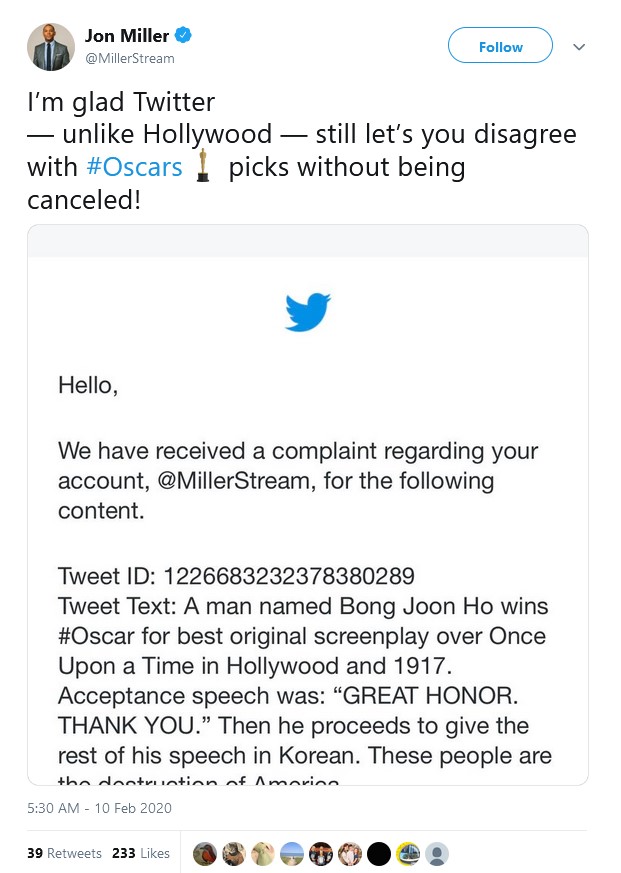

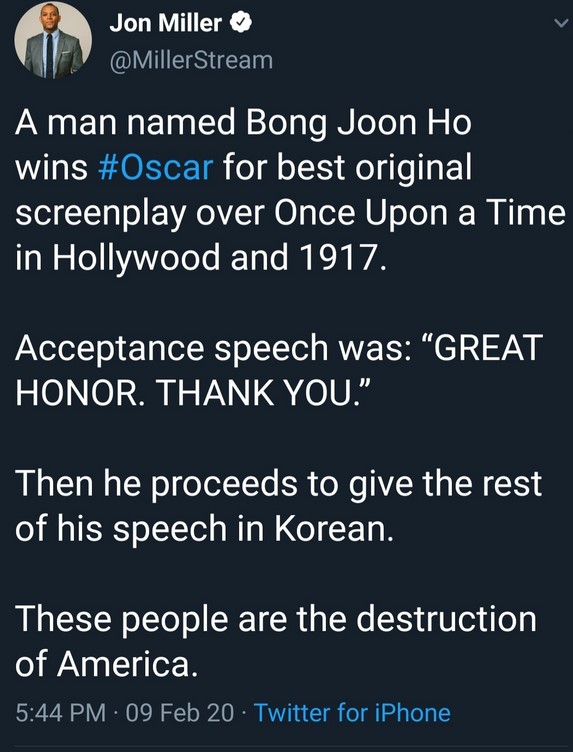

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and