(This is the ninth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The American Political Tradition.)

Sunset Park is a cozy part of Brooklyn trilling with children making midday escapes from big brick schools, with a few old factories that wail great threnodies whenever the moon winks a ditty about displaced residents on a cloudy night. There are robust workers and tight-knit families and bahn mi bistros and bustling bakeries from which one can savor the tantalizing nectar of glorious Spanish gossip squeezing into the streets. If you are tipsy after too many pints at the Irish pubs lining the southwestern fringe, there are 24 hour donut shops serving as makeshift diners, with loquacious jacks cooking up chorizo hash for any hungry ghost in a fix.

Sunset Park is a cozy part of Brooklyn trilling with children making midday escapes from big brick schools, with a few old factories that wail great threnodies whenever the moon winks a ditty about displaced residents on a cloudy night. There are robust workers and tight-knit families and bahn mi bistros and bustling bakeries from which one can savor the tantalizing nectar of glorious Spanish gossip squeezing into the streets. If you are tipsy after too many pints at the Irish pubs lining the southwestern fringe, there are 24 hour donut shops serving as makeshift diners, with loquacious jacks cooking up chorizo hash for any hungry ghost in a fix.

This is the region, along with East New York and Flatlands and Bensonhurst, where Brooklyn’s true soul still shines. It remains insulated from the Williamsburg hipsters oblivious to the high rise monstrosities now being hoisted near the East River or the yuppies who cleave to Park Slope’s gluten-free stroller war zone like children keeping to the shallow end of the pool. But the motley banter rivals the bright babble bubbling five miles east in Ditmas Park and even the chatty ripples that percolate just two miles south in Bay Ridge. In Sunset Park, you can pluck the city’s most enormous plantains from bold bodega bins bulging with promise, talk to the last honest bartender at Brooklyn’s best bowling alley, or walk beneath a Buddhist temple for some of the finest vegetarian Chinese grub in the region. It is a place of repose. It is a place of fun. It is a place to live.

Yet as great and as welcoming and as improbably enduring as this part of Brooklyn is, it could have been bigger. And for a long time, it was. Until Robert Moses came along.

There are many grim tales contained within Robert A. Caro’s The Power Broker — an alarmingly large and exquisitely gripping and undeniably great and insanely obsessive masterpiece of journalism documenting the most ruthless urban planner that New York, and possibly America, has ever known. If you love New York City even one tenth as much as I do, you will find many reasons to shout obscenities out your window after reading about what Robert Moses did to this mighty metropolis. It was Moses who killed off the free aquarium, open to all, that once stood in Battery Park. It was Moses who pitted reliable mass transit lines serving regular Janes and Joes against highways designed solely for those who had the shekels to buy and upkeep a car. It was Moses who believed African-Americans to be “dirty” and who, in building Riverside Park, stiffed the Harlem section of playgrounds (seventeen in the West Side; one in Harlem) and football fields (five to one). Moses was so casually racist that most of the parks he built, the parks that secured his popularity, served white middle-class New Yorkers. But working-class families needed these parks more and were often reduced to opening a fire hydrant in the streets and playing in the gutter during a hot summer.

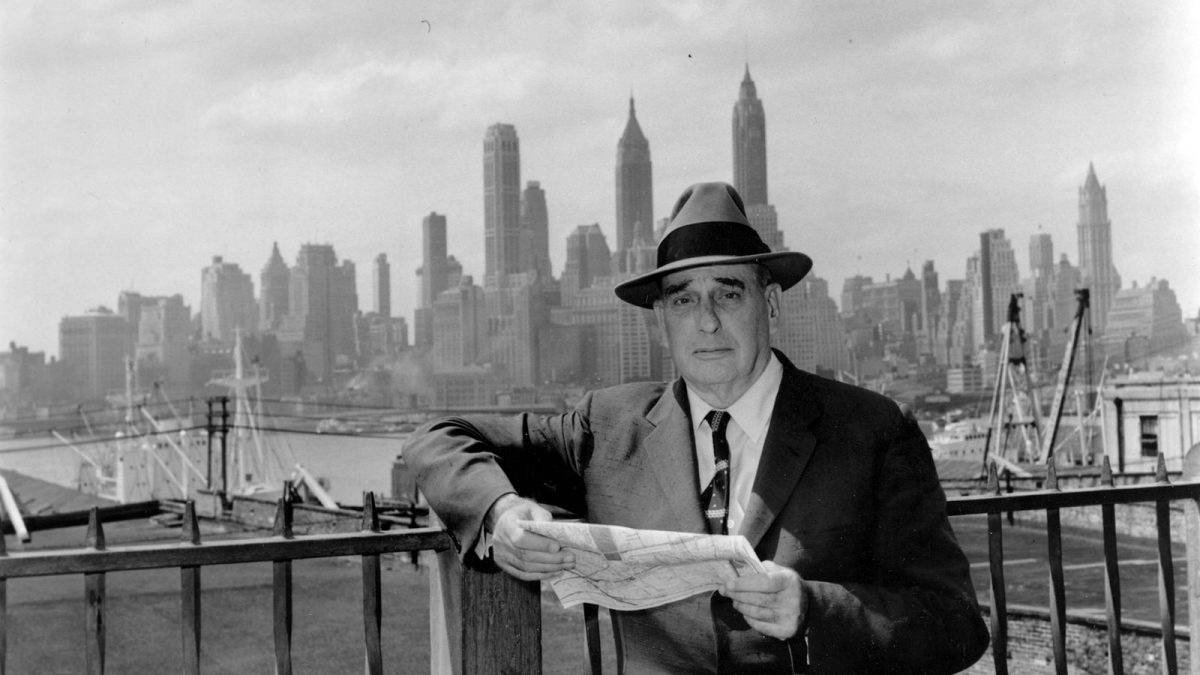

Not a single person in power will ever change the Manhattan skyline in the irreversible way that Moses did. Robert Moses had massive ambition, savvy savagery, limitless arrogance and energy, improbably large coffers that he willed together through a bridge bond ploy, a panache for grabbing and holding onto power, and a sick talent for persuading some of the most powerful figures of the 20th century to sign crooked agreements and/or get steamrolled into deals that screwed them over in quite profound ways.

For me, one of the acts that sums Moses up is the way in which he ripped out a major part of Sunset Park’s soul by erecting the Gowanus Expressway above Third Avenue. This is a toxic concrete barrier that still remains as cold and as gray and as unwelcoming as the bleakest rainstorm in December. To this very day, you can still hear the Belt Parkway’s thundering traffic as far away as Sixth Avenue. During a recent walk along Third Avenue on a somewhat chilly afternoon, I surveyed Moses’s handiwork and was nearly mowed down by a minivan barreling out of Costco, its back bulging with wasteful mass-produced goods, as a mad staccato honk pierced my ears with a motive that felt vaguely murderous.

Robert Moses wanted to make New York a city for automobiles, even though he never learned how to drive. And in some of the neighborhoods where his blots against natural urban life remain, his dogged legacy against regular people still persists.

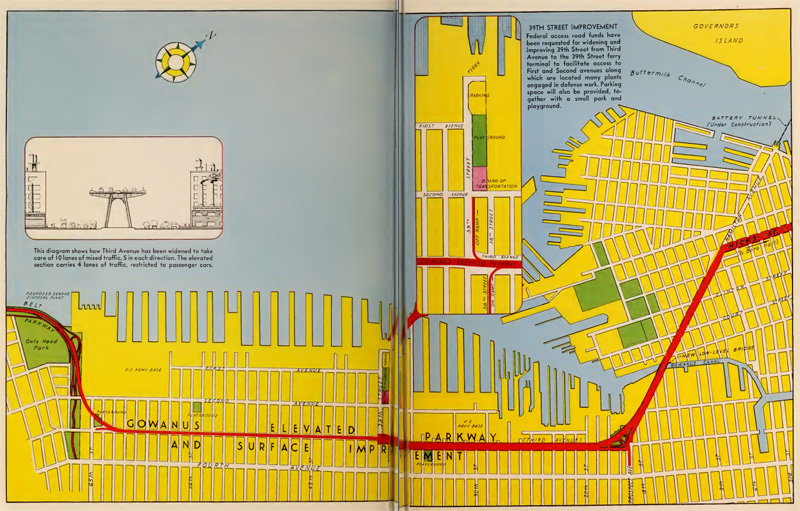

(Source: The Gowanus Improvement: November 1, 1941 / The Triborough Bridge Authority)

Sunset Park’s residents had begged Moses to build the expressway over Second Avenue. This was closer to the water and the industrial din and might have preserved the many small businesses and happy homes that once punctuated Third Avenue’s happy line. But Moses, citing the recently opened subway that now serves the D, N, and R underneath Fourth Avenue and the available support beams from the soon-to-be-demolished El, was determined to raise a freeway on Third Avenue that he claimed was much cheaper, even though the engineers who weren’t on Moses’s payroll had observed that one mere mile of freeway looping back to the shore wouldn’t substantially reduce the cost. But Moses had fought barons before and had made a few curving compromises while constructing the Northern State Parkway. Armed with the power of eminent domain and a formidable administrative power in which bulldozers and blockades could be summoned against opponents almost as fast as a modern day Seamless delivery, Moses was not about to see his vision vitiated. And if that meant calling the good parts of Sunset Park a “slum,” which it wasn’t, or spouting off any number of lies or threats to destroy perfectly respectable working class neighborhoods, then he’d do it.

As documented by Caro, the Gowanus stretched a raised subway line’s harmless Venetian-blind shadow into a dirty expanse that was nearly two and a half times as wide, wider than a football field and twice as onyx. The traffic lights were so swiftly timed that one had to be a running back to sprint beneath the smog-choking blackness to the other side of the street. The condensation from the steel pillars created such a relentless dripping that it transformed this once sunny thoroughfare into a dirt-clogged river Styx for cars. The cost was seven movie theaters, dozens of restaurants, endless mom and pop stores, butcher shops that raffled Christmas turkeys, and tidy affordable apartments — all shuttered. Moses did not plan for the increased industrial traffic that sprinkled into Sunset Park’s streets, just as he hadn’t for his many other freeways and bridges. Garbage and rats accumulated in the surrounding lots. There was violence and drugs and gang wars. The traffic tightened and slowed to a crawl, demanding more roads, more buildings to gut, more more neighborhoods to disrupt for the worse.

Who was this man? And why was he so determined to assert his will? He fancied himself New York’s answer to Georges-Eugène Haussmann (even reusing a doughnut-shaped building for the 1964 World’s Fair that the Parisian planner himself had put together in 1867), yet didn’t begin to earn a dime for his tyranny until his forties. (He lived off his family’s money and secured early planning jobs by declining a salary.) He thought himself a poet (not an especially good one), but if he had any potential prose style, it turned sour and hard and technocratic by the time he hit Oxford and received his doctorate at Columbia. He worked seemingly every hour of the day and took endless walks, memorizing the precise points where he would later build big parks and tennis courts. And he loved to swim, taking broad strokes well beyond the shores in his sixties and seventies with an endurance and strength that crushed men who were two decades younger. Small wonder that Moses gave the city so many public pools.

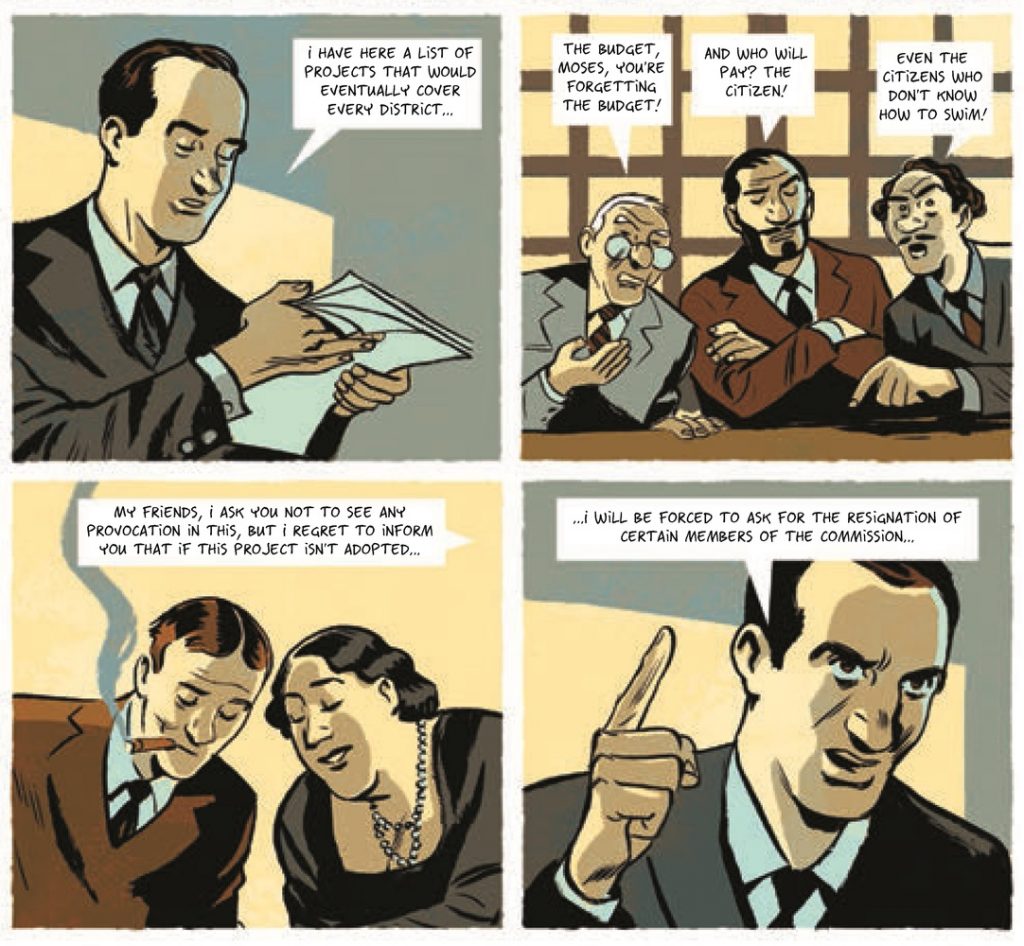

After I finished reading The Power Broker, I wanted to know more. I found myself plunging into the collected works of Jane Jacobs (Jacobs’s successful battle to save Washington Square Park was left out by Caro due to the enormity of The Power Broker‘s original manuscript), as well as Anthony Flint’s excellent volume Wrestling with Moses (documenting the battles between Moses and Jacobs), an extremely useful volume edited by Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson called Robert Moses and the Modern City that may be the best overview of every Moses project (and attempts, not entirely successfully, to refute some of Caro’s claims), as well as a wonderful graphic novel from Pierre Christin and Olivier Balez (Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City) which I recommend for anyone who doesn’t have enough time to read Caro’s 1,200 page biography written in very small print (although you really should read it).

I wanted to know how a man like Moses could operate so long without too many challenging him. His behavior often resembled a spoiled infant braying for his binky. When faced by an authority figure, Moses would often threaten to resign from a position until he got his way. Moses used this tactic so frequently that Mayor La Guardia once sent him a note reading, “Enclosed are your last five or six resignations; I’m starting a new file,” followed by city corporation counsel Paul Windels creating a pad of forms reading “I, Robert Moses, do hereby resign as _______ effective __________,” which further infuriated Moses.

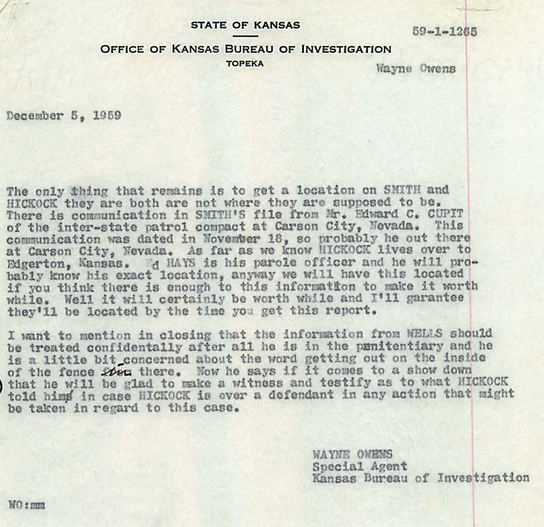

The answer, of course, was through money and influence that Moses had raised through a bridge bond scheme floated through the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, with Moses as Chairman:

Moses wanted banks to be so anxious to purchase Triborough bonds that they would use all of their immense power to force elected officials to give his public works proposals the approval that would result in their issuance. So although the safety of the banks’ money was already amply assured by Triborough’s current earnings (so great that each year the Authority collected far more money than it spent), by the irrevocable covenants guaranteeing that tolls could never be removed without the bondholders’ consent, and by Triborough’s monopoly, also irrevocable, that guaranteed them that if any future intracity water crossing were built, they would share in its tolls, too, Moses provided them with additional assurances. He maintained huge cash reserves — “Fantastic,” says Jackson Phillips, director of municipal research for Dun and Bradstreet; “the last time I looked they had ten years’ interest on reserve” — and when he floated the Verrazano bonds he agreed to lay aside — in addition to the existing reserves! — 15 percent ($45,000,000) of the cash he received for the new bond issue, and not touch it until the bridge was open and operating five years later. Purchasers of the Verrazano bonds could be all but certain that they could collect their interest every year even if the bridge never collected a single toll. Small wonder that Phillips says, “Triborough’s are just about the best bonds there are.” Wall Streeters may believe that “any investment is a bet,” but Robert Moses was certainly running the safest game in town.

In other words, Moses pulled off one of the most sinister financial games in New York history. The Triborough Authority could not only collect tolls on its bridges and capitalize on these receipts by issuing revenue bonds, which would in turn generate considerable income for Moses to fund his many public works projects, but it was capable of spending more money than the City of New York. Which meant that the city often had to come crawling back to Moses. And if the city or the state wanted to audit the Triborough Authority, this operation was so incredibly complicated that it would require at least fifty accountants working full-time for a year in order to comprehend it. Government did not have this kind of money to place safeguards against Moses. Moreover, it needed Moses’s financial assistance in order to provide for the commonweal.

It wasn’t until 1968, when Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Mayor John Lindsay put an end to these remarkable shenanigans by siphoning tolls into the newly created Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The bondholders might have sued over this. It was, after all, unconstitutional to uproot existing contractual obligations. But Rockefeller’s brother David happened to be the head of Chase Manhattan Bank. And Chase was the largest TBTA bondholder. In a glaring case of “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know,” the Triborough Authority as puppet organization for Moses was finished. Moses was forced to abandon his role. And the man’s political hold on New York was effectively finished after four decades of relentless building and endless resignation threats.

It seemed a fitting end for a man who had maintained such a stranglehold over such a large area. Six years later, Robert Caro’s biography appeared. Moses wrote a 23 page response shortly after the book’s publication. Caro’s rebuttal was five paragraphs, concluding with this one:

It is slightly absurd (but typical of Robert Moses) to label as without documentation a book that has 83 solid pages of single-spaced, small-type notes and that is based on seven years of research, including 522 separate interviews.

Next Up: Ralph Ellison’s Shadow and Act!

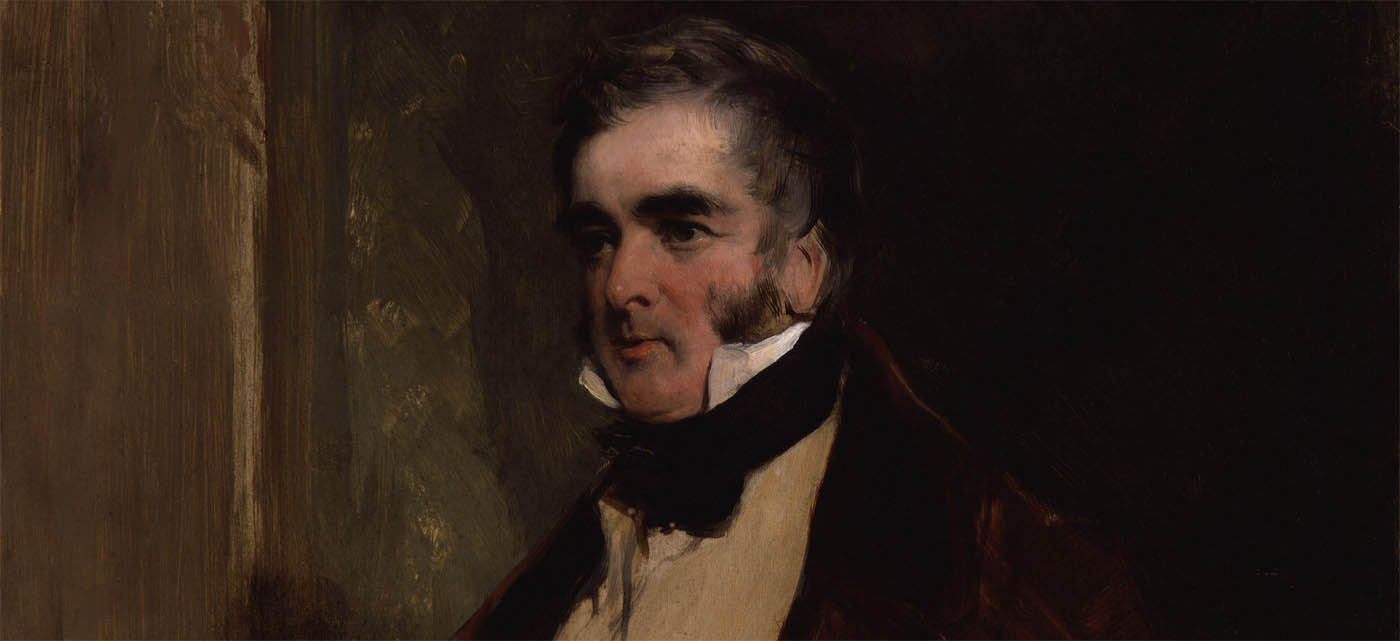

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.