(This is the twenty-first entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: Studies in Iconology.)

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

He could just as easily have been discussing the current doddering charlatan now forcing many otherwise respectable citizens into recuperative nights of heavy drinking and fussy hookups with a bespoke apocalyptic theme, but Twain’s sentiments do say quite a good deal about the cyclical American affinity for peculiar outsiders who resonate with a populist base. As I write these words, Bernie Sanders has just decided to enter the 2020 Presidential race, raising nearly $6 million in 24 hours and angering those who perceive his call for robust social democracy to be unrealistic, along with truth-telling comedians who are “sick of old white dudes.” Should Sanders run as an independent, the 2020 presidential race could very well be a replay of Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party run in 1912.

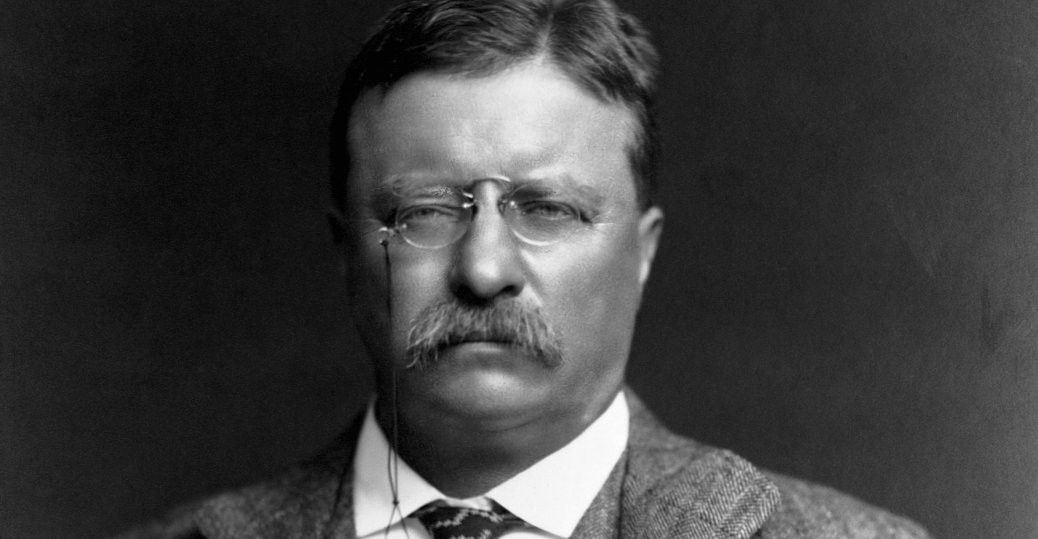

Character ultimately distinguishes a Chauncey Gardner couch potato from an outlier who makes tangible waves. And it is nearly impossible to argue that Teddy Roosevelt, while bombastic in his prose, often ridiculous in his obsessions, and pretty damn nuts when it came to the Rough Riders business in Cuba, did not possess it. Edmund Morris’s incredibly compelling biography, while subtly acknowledging Teddy’s often feral and contradictory impulses, suggests that Roosevelt was not only the man that America wanted and perhaps needed, but reminds us that Roosevelt also had the good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. Had not Vice President Garret Hobart dropped dead because of a bum ticker on November 21, 1899, and had not a sour New York Republican boss named Tom Platt been so eager to run Teddy out of Albany, there is a good chance that Roosevelt might have ended up as a serviceable two-term Governor of New York, perhaps a brasher form of Nelson Rockefeller or an Eliot Spitzer who knew how to control his zipper. Had not a Russian anarchist plugged President McKinnley two times in the chest at the Temple of Music, it is quite possible that Roosevelt’s innovative trust busting and his work on food safety and national parks, to say nothing of his crazed obsession with military might and giving the United States a new role as international police force, would have been delayed altogether.

What Roosevelt had, aside from remarkable luck, was a relentless energy which often exhausts the 21st century reader nearly as much as it fatigued those surrounding Teddy’s orbit. Here is a daily timetable of Teddy’s activities when he was running for Vice President, which Morris quotes late in the book:

| 7:00 A.M. |

Breakfast |

| 7:30 A.M. |

A speech |

| 8:00 A.M. |

Reading a historical work |

| 9:00 A.M. |

A speech |

| 10:00 A.M. |

Dictating letters |

| 11:00 A.M. |

Discussing Montana mines |

| 11:30 A.M. |

A speech |

| 12:00 |

Reading an ornithological work |

| 12:30 P.M. |

A speech |

| 1:00 P.M. |

Lunch |

| 1:30 P.M. |

A speech |

| 2:30 P.M. |

Reading Sir Walter Scott |

| 3:00 P.M. |

Answering telegrams |

| 3:45 P.M. |

A speech |

| 4:00 P.M. |

Meeting the press |

| 4:30 P.M. |

Reading |

| 5:00 P.M. |

A speech |

| 6:00 P.M. |

Reading |

| 7:00 P.M. |

Supper |

| 8-10 P.M. |

Speaking |

| 11:00 P.M. |

Reading alone in his car |

| 12:00 |

To bed |

That Roosevelt was able to do so much in an epoch before instant messages, social media, vast armies of personal assistants, and Outlook reminders says a great deal about how he ascended so rapidly to great heights. He could dictate an entire book in three months, while also spending his days climbing mountains and riding dozens of miles on horseback (much to the chagrin of his exhausted colts). Morris suggests that much of this energy was forged from the asthma he suffered as a child. Standing initially in the shadow of his younger brother Elliott (whose later mental collapse he callously attempted to cover up to preserve his reputation), Teddy spent nearly his entire life doing, perhaps sharing Steve Jobs’s “reality distortion field” in the wholesale denial of his limitations:

In between rows and rides, Theodore would burn off his excess energy by running at speed through the woods, boxing and wrestling with Elliott, hiking, hunting, and swimming. His diary constantly exults in physical achievement, and never betrays fear that he might be overtaxing his strength. When forced to record an attack of cholera morbus in early August, he precedes it with the phrase, “Funnily enough….”

Morris is thankfully sparing about whether such superhuman energy (which some psychological experts have suggested to be the result of undiagnosed bipolar disorder) constitutes genius, only reserving the word for Roosevelt in relation to his incredible knack for maintaining relations with the press — seen most prominently in his fulsome campaign speeches and the way that he courted journalistic reformer Jacob Riis during his days as New York Police Commissioner and invited Riis to accompany him on his nighttime sweeps through various beats, where Roosevelt micromanaged slumbering cops and any other layabout he could find. The more fascinating question is how such an exuberant young autodidact, a voracious reader with preternatural recall eagerly conducting dissections around the house when not running and rowing his way with ailing lungs, came to become involved in American politics.

Some of this had to do with his hypergraphia, his need to inhabit the world, his indefatigable drive to do everything and anything. Some of it had to do with deciding to attend Columbia Law School so he could forge a professional career with his new wife Alice Hathaway Lee, who had quite the appetite for social functions (and whose inner life, sadly, is only superficially examined in Morris’s book). But much of it had to do with Roosevelt regularly attending Morton Hall, the Republican headquarters for his local district. Despite being heckled for his unusual threads and side-whiskers, Roosevelt kept showing up until he was accepted as a member. The Roosevelt family disapproved. Teddy reacted in anger. And from moment forward, Morris writes, Roosevelt desired political power for the rest of his life. Part of this had to do with the need for family revenge. Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. suffered a swift decline in health (and quickly died) after Roscoe Conklin and New York State Republicans set out to ruin him over a customs collector position.

These early seeds of payback and uncompromising individualism grew Roosevelt into a fiery oleander who garnered a rep as a fierce and feisty New York State Assemblyman: the volcanic fuel source that was to sustain him until mortality and dowdiness sadly caught up with him during the First World War. But Roosevelt, like Lyndon B. Johnson later with the Civil Rights Act (documented in an incredibly gripping chapter in Robert A. Caro’s Master of the Senate), did have a masterful way of persuading people to side with him, often through his energy and speeches rather than creepy lapel-grabbing. As New York Police Commissioner, Roosevelt upheld the unpopular blue laws and, for a time, managed to get both the grumbling bibulous public and the irascible tavern keepers on his side. Still, Roosevelt’s pugnacity and tenacity were probably more indicative of the manner in which he fought his battles. He took advantage of any political opportunity — such as making vital decisions while serving as Acting Secretary of the Navy without consulting his superior John Davis Long. But he did have a sense of honor, seen in his refusal to take out his enemy Andrew D. Parker when given a scandalous lead during a bitter battle in New York City (the episode was helpfully documented by Riis) and, as New York State Assemblyman, voting with Democrats on March 7, 1883 to veto the Five-Cent Bill when it was discovered to be unconstitutional by then Governor Grover Cleveland. Perhaps his often impulsive instincts, punctuated by an ability to consider the consequences of any action as it was being carried out, is what made him, at times, a remarkable leader. Morris documents one episode during Roosevelt’s stint as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in which he was trying to build up an American navy and swiftly snapped up a Brazilian vessel without a letter. When the contract was drafted for the ship, dealer Charles R. Flint noted, “It was one of the most concise and at the same time one of the cleverest contracts I have ever seen.”

Morris is to be praised for writing about such a rambunctious figure with class, care, and panache. Seriously, this dude doesn’t get enough props for busting out all the biographical stops. If you want to know more about Theodore Roosevelt, Morris’s trilogy is definitely the one you should read. Even so, there are a few moments in this biography in which Morris veers modestly into extremes that strain his otherwise eloquent fairness. He quotes from “a modern historian” who asks, “Who in office was more radical in 1899?” One zips to the endnotes, only to find that the “historian” in question was none other than the partisan John Allen Gable, who was once considered to be the foremost authority on Teddy Roosevelt. Morris also observes that “ninety-nine percent of the millions of words he thus poured out are sterile, banal, and so droningly repetitive as to defeat the most dedicated researcher,” and while one opens a bountiful heart to the historian prepared to sift through the collected works of a possible madman, the juicy bits that Morris quotes are entertaining and compelling. Also, to be fair, a man driven to dictate a book-length historical biography in a month is going to have some litters in the bunch.

But these are extremely modest complaints for an otherwise magnificent biography. Edmund Morris writes with a nimble focus. His research is detailed, rigorous, and always on point, and he has a clear enthusiasm for his subject. Much of Morris’s fall from grace has to do with the regrettable volume, Dutch, in which Morris abandoned his exacting acumen and inserted a version of himself in a biography of Reagan. This feckless boundary-pushing even extended into the endnotes, in which one Morris inserted references to imaginary people. He completely overlooked vital periods in Reagan’s life and political career, such as the Robert Bork episode. Given the $3 million advance and the unfettered access that Morris had to Reagan, there was little excuse for this. Yet despite returning valiantly to Roosevelt in two subsequent volumes (without the weirdass fictitious asides), Morris has been given the Wittgenstein treatment (“That whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must remain silent”) by his peers and his colleagues. And I don’t understand why. Morris, much like Kristen Roupenian quite recently, seems to have been needlessly punished for being successful and not living up to a ridiculous set of expectations. But The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, which rightfully earned the Pulitzer Prize, makes the case on its own merits that Morris is worthy of our time, our consideration, and our forgiveness and that the great Theodore Roosevelt himself is still a worthwhile figure for contemporary study.

Next Up: Martin Luther King’s Why We Can’t Wait!

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”