[This is the first in a series of dispatches relating to the 2011 New York Film Festival. All of Reluctant Habits’s NYFF posts can be located here.]

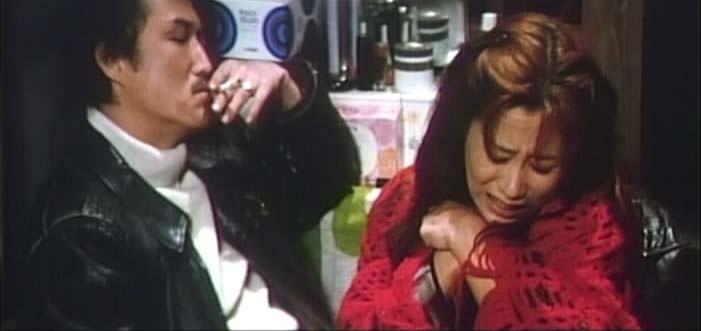

In considering the trashy pink film Woman with Red Hair, I must first ruminate upon the film’s commitment to verisimilitude, as well as its intricate moral framework. A young woman casually loses her virginity during a gang rape, becomes pregnant, and uses this as leverage to snag one of the two strapping young attackers – an unnamed jerk who often wears a blue headband – as her husband. This magnificent pillar to manhood has an equally upstanding companion with Kozo (Renji Ishibasi), who enjoys smiling smugly for the camera when not sexually humiliating the titular woman with red hair (Junko Miyashita), whose ass is often deliberately positioned to undulate before the audience. It is a tribute to this film’s hypnotic hypocrisy that, as Kozo forces the woman with the red hair to take his cock into her mouth, an oppressive black rectangle appears on the right side of the frame, with Miyashita’s legs flailing behind it. Despite this film’s firm commitment to debasing women (one charming ditty that the two men croon contains the lyric “She’ll say no when she means yes”), in 1979, it lacks the authority to show pussy.

We are informed that the young married couple living downstairs are junkies, but our only indication of their drug use is through their screechy wails (compared later in the film to a pig), leaving one to wonder if they are in a permanent state of withdrawal or if they represent some more enlightened viewer having to contend with this plodding movie, selected as part of a Nikkatsu celebration for the 49th New York Film Festival. In the middle of wanton carnality, our ruddy-maned heroine casually asks, “Ever try heroin?” While the two strapping young creeps talk to their boss about their special driving skills and discuss whether or not they need licenses, a young woman stands outside in the rain, a testament to their chivalry. She enters the room not long after, only to be slapped repeatedly. The woman with red hair alludes to having two young children, yet like the track marks and heroin supply downstairs, they remain unseen. In another episode, a somewhat older woman remembers a “foam dance,” which involves lathering yourself up with soap and gyrating upon a inflatable mattress next to a tub. Just wait for your husband (or really, given this film’s outlook, any man) to arrive and he’ll start schtupping you.

My favorite part of Woman with Red Hair was when Kozo, letting his pummeled paramour fuck another man, walks out into the pouring rain and starts jerking off in an alley. Why? Well, you see, he’s so turned on by the prospect of another man banging the woman he’s with that he just can’t wait to shoot his load. Alas, Kozo is interrupted in his perfervid pumping by a man (presumably, the pink film’s idea of comic relief) who asks him for some spare yen so that he can fuel his alcoholism. And because his request is understandably denied under the circumstances, he somehow accompanies Kozo to another apartment, where Kozo drinks and fucks another woman and the alcoholic remains plastered beneath him.

Welcome to the wacky worldview of filmmaker Tatsumi Kumashiro, who also gave us 1988’s Love Bites Back (but do the “victims” deserve it?), 1986’s Women Who Do Not Divorce (does that mean the women who do divorce shouldn’t be bothered with?), and two films in 1973 with “wet” in the title. Woman with Red Hair was one of the more acclaimed films of the Roman Porno line commissioned by Nikkatsu. In 1971, the revered Japanese studio faced bankruptcy and had switched from action movies and blockbusters to softcore films in a desperate effort to remain financially viable. (To give you a sense of how drastic this decision was, imagine if Paramount or Warner Brothers decided to start making softcore movies instead of Hollywood blockbusters.)

But Woman with Red Hair, despite ample justification by Japanese film buffs, is hardly In the Realm of the Senses. Most of its long stretches are dreadfully banal. Conversation about getting a new gas heater and the price of eggs at the local supermarket sounds like blue-collar authenticity, until you realize that it doesn’t actually articulate anything about the characters or their culture. So you’re left to rue upon why so many people are interested in red penises (and why one man in this film is fond of muddying his member with red lipstick). When the closing credits rolled, I was stunned to learn that Woman with Red Hair was based on a novel by Japanese intellectual Kenji Nakagami. And while there’s a definite working-class thrust to the film (workers become violent and sexual when they are not permitted work), I didn’t feel that the film presented any sexual subversiveness on the level with Lina Wurtmuller or early Almodovar. Once you confront the atavistic imagery, you’re left with a fairly pedestrian and toothless flick that no amount of metaphorical rain can flush into a meaningful realm.