A new issue of h+ Magazine has left the building. The quarterly magazine, edited by the incomparable R.U. Sirius, features contributions from the likes of Alex Lightman, Douglas Rushkoff, Tara E. Hunt, John Shirley, and yours truly. (You can find my unusual comparative review of Mac Montandon’s Jetpack Dreams and Brian Rafferty’s Don’t Stop Believin’ on Page 67.)

Month / February 2009

Amazon Profiting Incommensurately Off Bloggers?

As I pointed out more than a year ago, Amazon has been offering monthly blog subscriptions to Kindle readers, but, in some cases, it hasn’t been paying the bloggers a reasonable cut of the revenue. And as my investigation revealed, in some cases, Amazon didn’t even bother to ask permission from the bloggers. While the monthly subscription cost has gone down to 99 cents per month, as Rebecca Skloot discovered on Twitter this afternoon, Maud Newton’s site is now for sale on the Kindle. (Maud has since revealed that a nonexclusive contract she signed with Newstex gives them the right to distribute her content through the Kindle.)

But there’s a big question here. If Amazon makes 99 cents per subscription, how much of this goes to the bloggers?

I am now in the early stage of a major investigation to determine, once again, if the bloggers listed on the Kindle store are collecting any commensurate revenue or granting their permission to Amazon to have their blogs distributed. And I will be updating this site with my findings. If your blog is listed on the Kindle Store, please contact me so that we can begin to hold Amazon accountable for seizing content generously offered for free and selling it to others on the open market.

There are currently 1,280 blogs listed at the Amazon Kindle Store.

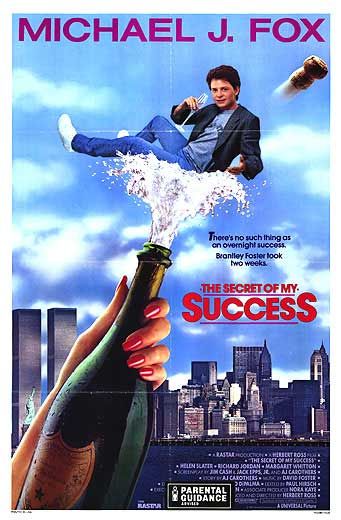

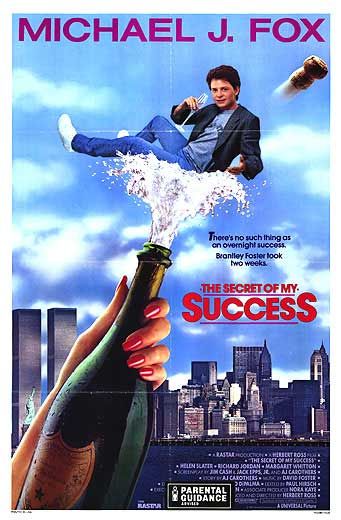

Success

Now imagine living a life, like Elizabeth Gilbert, in which you’re convinced that your greatest success is behind you. That seems to me a boring and not particularly ebullient existence: you’re holding onto a trajectory in which you’ve done the best you can and there isn’t anything better that you can do. You’ve hit the big time, and that’s it! Finito! It’s all downhill from here! But at least some elitist organization meeting out in the middle of nowhere will pay you a good sum of money to speak to a bunch of people who seem to believe they are successes based on a few large sums they’re filling into the blanks of their 1040s. And it’s all a bit confusing because the speaker has already reached the highest form of success possible! And the people who are gathered together at the secluded retreat have already predetermined that they are successes, based on being better than the sad Joe Sixpacks who must settle for the YouTube videos kindly distributed on the Web. I suppose, if you’re Gilbert or one of these dutiful attendees, you’re not really planning on being a better success, or the success that you have is somehow proportional to the amount that is in your checking account. But is that really success? Or is that boasting? And since boasting falls into that regrettable terrain occupied by arrogance, are the TED folks, in this particular instance, arrogance enablers?

Now imagine living a life, like Elizabeth Gilbert, in which you’re convinced that your greatest success is behind you. That seems to me a boring and not particularly ebullient existence: you’re holding onto a trajectory in which you’ve done the best you can and there isn’t anything better that you can do. You’ve hit the big time, and that’s it! Finito! It’s all downhill from here! But at least some elitist organization meeting out in the middle of nowhere will pay you a good sum of money to speak to a bunch of people who seem to believe they are successes based on a few large sums they’re filling into the blanks of their 1040s. And it’s all a bit confusing because the speaker has already reached the highest form of success possible! And the people who are gathered together at the secluded retreat have already predetermined that they are successes, based on being better than the sad Joe Sixpacks who must settle for the YouTube videos kindly distributed on the Web. I suppose, if you’re Gilbert or one of these dutiful attendees, you’re not really planning on being a better success, or the success that you have is somehow proportional to the amount that is in your checking account. But is that really success? Or is that boasting? And since boasting falls into that regrettable terrain occupied by arrogance, are the TED folks, in this particular instance, arrogance enablers?

Is it becoming for any artist or curiosity seeker to boast about any particular success? Or to put a final value on what success is? Is success, as Booker T. Washington once suggested, something to be measured not by the position one has reached in life, but through the obstacles that a person has overcome? And is it not incumbent for any decent person to create new obstacles so that success becomes meaningless? (Eat, pray, and love all you want. But if your soul is hollow and solipsistic in the first place, you’ll never get anywhere.)

By that measure, success becomes something unmeasurable and, in all likelihood, unattainable. It’s a bit like an experiment that the Caltech folks spring on first-year students. The story told to me about two decades ago is this: You put a girl at the end of the gym. You tell a group of boys that if they can get from one end of the gym to the other, they can kiss the girl. But the deal is this. They must constantly move one-half the distance that they started out with over a series of stages. Now it seems at first, particularly in the early stages, that you’re going to get to the other end of that gym. But, of course, as we all know, if you’re constantly moving one-half the distance, you’re constantly splitting the distance. One half becomes one fourth becomes one eighth becomes one sixteenth. You get the picture. But the incentive to kiss that girl — perhaps similar to the value of success we’re bandying about here — overwhelms any rational sense. You’re never going to kiss that girl if you constantly move forward by one half of the distance with each move. But perhaps you will if you never agreed to this condition in the first place.

Success then, like the Caltech experiment, is one of those tricky yardsticks that really doesn’t amount to a hill of beans if you’re quite happy putting your efforts into evolving, trying to get better, creating more obstacles. The honest person in this situation will tell you that she really hasn’t a clue as to whether she’s a success or not, because the honest person is forever shifting. Not letting some weird economic qualifier hinder or destroy what she does. Not letting some mythical unit called “success” put a cap on what she does. Casablanca, as we all know, was just a studio picture. It’s a fine motion picture, but it wouldn’t have happened if Michael Curtiz and everybody else had worried about how much of a success it should be or whether it represented the maximum amount of success that the cast and crew would ever obtain.

Such a burden seems counterintuitive to the wonderful impulse of being. Why should a subsequent failure matter so much because it follows a “success,” if, after all, the person working on the project is simply pumping the work out in the same daily manner performed in producing the “success?” (Unless, of course, there was never any plan to be distinct in the first place, and a convenient “book advance” permitted the person to live in a sad bubble.) Is this the way that we ferret out the frauds? We’re fond of penalizing the “lesser” work, when we really should be looking at the person’s entire trajectory. The real element to be concerned about here is the person who refuses to set up obstacles, the individual who settles into a declivity rather than fails quite naturally (and accidentally) in the act of producing more work. The person who takes the check to spread misinformation. The type who doesn’t understand that risk and failure are virtues. The austere soul who refuses to hop on board the wild rollercoaster of life.

The Publishing Industry: An Economic Thought Experiment

Case Study 1: During Presidents Day Weekend, the software company Valve tried out an experiment. Valve, the company behind the successful Half-Life franchise, temporarily halved the price for Left 4 Dead, a cooperative first-person shooter title, from $49.99 to $24.99, over the course of a few days through its centralized Steam client. The results exceeded Valve’s wildest expectations. Sales rose 3,000 percent, and the revenue generated over the weekend dwarfed the game’s sales during its launch. By temporarily offering the game at a price point that was affordable to everybody, and making the game instantly downloadable, not only was Valve able to breathe life into a four month-old game, but they were able to get more people attracted to the product. Valve’s DRM policy is fairly straightforward. If you purchased a game, you can download the game on another computer, should you login as that user. (This was, incidentally, how I was able to redownload Half-Life 2 last year after a move, when I had accidentally deleted my Steam files and couldn’t find the original disc that I had purchased. One overnight download and I was back in action, happily fragging alien creatures.)

There are a number of important points here.

1. Unlike the Kindle or the eReader, there isn’t an expensive entry point here. You don’t have to pay $400 to get started on Steam. You can download the client for free on the hardware you already have and just pay for the games. The cost is minimal and affordable.

2. Unlike the Kindle, the DRM rights aren’t limited to the device or a singular computer (unlike last year’s Spore DRM controversy). If your hard drive goes kaput, then you can download the game again on another computer. Simply identify yourself through your Steam ID, and you can download the game on as many PCs as you want.

3. By offering a variable price point that considered what the general (and probably out-of-work) consumer wanted, Valve was able to generate more interest in the title than they anticipated.

Case Study 2: For seven years, the comic book industry has offered Free Comic Book Day. The idea is this. The general consumer goes into a store, gets a few free comic books, and is reminded why comics are great in the first place. The consumer divagates through a store and purchases more titles. And the whole thing gets considerable media attention.

The smart retailers, like Mike Sterling, spiff up their stores and offer additional in-store sales: 10% off graphic novels, four for the price of three on manga. (And in Sterling’s case, the graphic novel sales alone paid for the cost of the FCBD floppies.) You get the community involved by making celebratory cakes. You get to find out what titles get people excited. You get to form relationships with potential new customers. You move product. (For Heroes Aren’t Hard to Find owner Shelton Drum, FCBD is one of the top three sales days of the year.) You get to demonstrate to people why they need to keep going to a comic book store. And, like the Valve experiment, there’s no expensive entry point. Plus, the consumers will walk away from the store with something.

Case Study 3: Board game manufacturers are now considering something that worked very well during the Great Depression. If you offer an American family a reasonably priced form of entertainment that will last for a long time, they may very well set aside $20 to buy the product during lean times. (According to a Hasbro spokesman, board games and puzzle sales rose 2% in 2008.)

Case Study 4: Soft Skull had a surprisingly profitable year in 2008 because the efforts here were focused on (1) knowing the audience and (2) working hard to connect the audience as intimately and personally as possible. (In other words, if you treat your audience like some dopey general demographic, why on earth would they bother to buy your product?)

So what do we take away from all this? How did these successes emerge during a recession? In each case, the individual’s daily realities were respected. There probably isn’t a lot of money to go around in the household, but there was just enough cash for a micropayment. The individual wasn’t asked to invest money she didn’t have in some fancy-schmancy technological doodad before purchasing an affordable form of entertainment. The individual received an affordable long-term option that would keep her entertained or occupied for many hours. The individual did not have to deal with invasive DRM that suggested she was a criminal. The individual was listened to and treated with respect by the retailer. And the retailer never assumed that it would make a sale. But the retailer likewise had opportunities to listen to what the audience wanted and to find out what it may be doing wrong.

So if there is a modicum of money to be made in a limping economy, why aren’t today’s publishers and book retailers accounting for these realities?

Most people who are now out of work cannot afford a $30 hardcover, let alone a $400 Kindle. And yet corporate arrogance keeps these units at prices unreasonable to someone unemployed who needs a little entertainment during an economic downturn. And what is the result? Anger boils to the surface. Long-term relationships with potential customers suffer because the corporate overlords remain inflexible on price point.

So if you’re a publisher or a bookseller, consider this. If you know that people can afford a $10 hardcover (as opposed to a $30 hardcover), why in the hell aren’t you learning from these examples? Why aren’t you offering a Valve-like time window where people can walk into a bookstore and purchase a few $10 hardcovers over a weekend? And why aren’t you promoting the hell out of this? Why isn’t there a Free Book Day in which you get to introduce people to the joys of books and you get to know your customers? Why aren’t you forming intimate and personal connections with readers so that they’ll continue to buy your products? And why aren’t you considering that they really don’t have a hell of a lot of cash to throw around right now?

Are you willing to take a hit on the first spate of units, much as Valve did, if there’s the possibility that you may just hit a thundering mother lode after the initial curve? Or do you want to continue to turn off readers?

Can you truly afford to refer to the territory between the coasts as “flyover states” when there are good people there who want to enjoy books right now? If you’re an author or a publicist, can you afford to thumb your nose up at any media opportunity that isn’t the New York Times Book Review? Or are you not really all that interested in establishing relationships? If you’re a newspaper or a magazine, why aren’t you citing the blogs or providing helpful URLs to the blogs that break the stories or make the connections? Why aren’t you hiring bloggers to write the articles? Don’t you realize that online audiences might come your way if they know that a particular voice is attached? And here’s a bold concept to consider. If you took the top 10,000 bloggers on Technorati and paid each of them $40,000 a year — a livable wage that would permit them all to carry out their work, which could also include serious investigations — that’s a cost of $400 million. For $400 million a year, someone could get the top 10,000 bloggers reporting for newspapers and seamlessly integrate their content into the great whole. And the newspapers could offer copy editing and journalistic resources so that their voices might improve. (Of course, you’d have to accept their unadulterated voices. For these voices, differing from the mainstream, are what caused these bloggers to rise up in the first place.)

If today’s publishers, booksellers, and media outlets hope to answer these questions and produce results similar to the above four case studies, then bolder ideas and experiments need to be attempted and shared with transparency in mind. It is not economically feasible to sit back and wait for the magic results of the stimulus package to trickle around. The current Dow Jones declivity has demonstrated the follies of lame ducks. The previous ways of doing things may very well be at an end: possibly with some permanence. But we won’t know this for sure until those in positions of power attempt a little innovation and modify the current formulas that aren’t working. Change, it seems, was something we hoped somebody else would do. But it’s now become quite apparent that today’s real innovators are those with the courage to take hold of their own destinies.

[UPDATE: Since this post, like many of these lengthy ones, originated from thoughts and musings I expressed on Twitter, here are a few related thoughts from others on the subject. @jimmydare observes that Orbit is experimenting with the $1 ebook. @AnnKingman pointed out that Record Store Day was a huge success for her local record store. (More details on what goes on at Record Store Day here.) @thebookmaven suggests that a Free Book Day might be one way that independent bookstores can compete with ebooks, and also suggests a $5 Book of Your Choice Day.]