On September 16, 2022, the National Book Awards announced its fiction longlist. That very same morning, I started working the phones, contacting publishers and asking them to send me review copies. Some publishers were incredibly gracious (even as they rightly questioned my monomania). My wild literary experiment was simple: what happens when one hardcore bald man in Brooklyn with a hopelessly iconoclastic streak reads all ten longlist titles before the October 4th finalist announcement?

I finished reading the books on September 30th. Then my computer broke down. Then I fixed my computer. Now it is one day before the announcement and I have arrived, just in the nick of time, to raise a little hell and serve up some heartfelt praise.

I have no connection with any of these authors. The only conflict of interest here involves one of the books being edited by a loathsome liar and rumormongering backstabber whom I strongly detest. He has pushed many kind heads beneath the undertow for careerist purposes and, despite leading a smear campaign accusing bloggers of unethical journalism many years ago, he has evinced pure unethical venality in regularly buying books for the publisher he represents that are agented by his partner, thus securing a crooked two-income stream. Still, quality work is quality work and this scumbag’s unfortunate association with a book I happened to love did not deter me in any way from ranking the book very high. (I have elided this man’s name, as well as that of another hateful and treacherous individual cited below, to make it slightly more difficult for him to name search himself. But if you really need to know who they are, Google is free.)

I am certain that many of the weak-kneed literary networkers regularly practicing social media fellatio will be offended by what I have to say. But unlike these deplorable cheerleaders regularly selling out their principles for a galley, I’m constitutionally incapable of kissing anyone’s ass, particularly if the work or the writer is irredeemably mediocre. In a world of vulpine backslapping, sham gatekeeping, transactional relationships, and cowardly “No haters” review policies, I felt that it was my duty to offer a brutally honest and sincerely passionate take on this year’s slate. What this means is that any endorsement you get from me is the genuine article. I’ll leave the smoke-blowing to the inveterate blurb whores and the blue checkmarks who regularly stump for the banal and the unremarkable to win likes and followers.

Let me state from the outset that the judges mostly got it right this year. This is the most interesting fiction longlist that the National Book Awards has served up in years. And if this is a sign of lists to come, then the National Book Awards may indeed regain its prestige from the payola horrorshow that only Tom LeClair has had the stones to rightly call out. Liberated from the previous executive director’s disastrous and self-serving stewardship, which ushered in an onslaught of wildly overrated commercial titles and turned the medal into a popularity contest rather than a true gauge of literary merit and caused any self-respecting reader to turn to the Booker Prize winners for real heft (Anna Burns’s Milkman, Bernardien Evanisto’s Girl, Woman, Other, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, and Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain all represented distinctive literature that the National Book Awards used to be about before the previous director vitiated the award’s credibility with her relentless efforts to dumb everything down), the National Book Awards are something that we can be proud of again. The previous director is so evil and deplorable that, according to two unimpeachable sources whose anonymity I shall never betray to anyone, she once announced that she would throw a lavish fete if I successfully committed suicide. I suspect that such unbridled sociopathic sentiments were one of the primary reasons why the National Book Awards plummeted in recent years — drifting away from empathy-driven titles depicting what it is to be alive. Fortunately, Fiction Chair Ben Fountain has smartly guided his team of judges to single out weirdos, risk-takers, and reliable outliers. Short stories are very well represented this year and the selections here are largely superb. Young and emerging writers have also received their proper due. This is, in short, a well-considered list.

But the longlist is far from perfect. There were only two titles that I deeply regretted reading. Still, I can state with confidence that three of the represented books are bona-fide masterpieces and deserve to be included among the five finalists. There were also a few literary names (new to me) who greatly impressed me with their fierce talent and blazing originality. So without further ado, here’s the ranked longlist!

Unranked: Fatimah Asghar, When We Were Sisters

This is the only longlist title with a publication date weeks after the finalist announcement. The supercilious mooks at One World Books — operating from the “There’s always one guy at the party who pisses in the pool” playbook — failed to respond to my requests for a review copy by email, phone, and Instagram. They didn’t even have the decency to say no. ThusI have been forced with great reluctance and disappointment to exclude this bank from my rankings. If Asghar makes it to the finalists, I will be more than happy to review it.

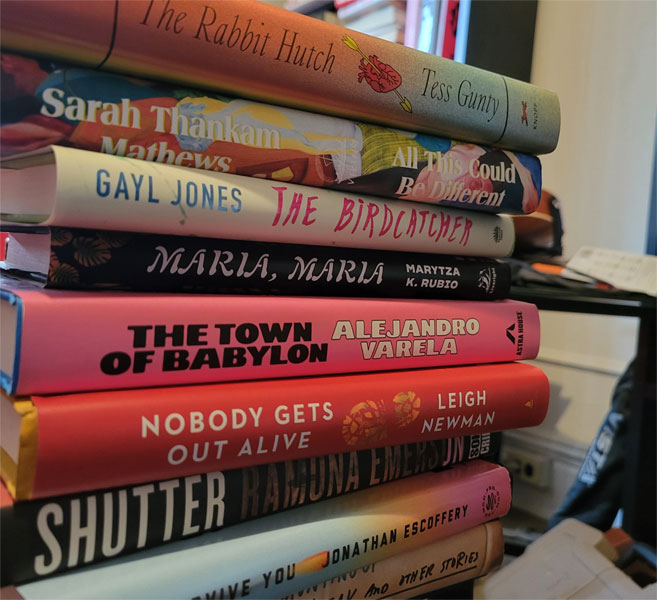

9. Alejandro Varela, The Town of Babylon

You know how when you go to a bar and there’s some guy who starts telling you his life story? And he’s completely uninteresting. And he won’t shut up. Even when you’re nice about it. Even when you buy the guy drinks. He keeps coming at you. He lives to talk and dominate. He’s so in love with all the dull and dry details of his sad life and he still somehow believes that he’s remarkable. Well, this is how I feel about Alejandro Varela and his prose. The premise of being nonwhite and queer in suburbia really should have worked, but Varela is so thin and lackluster with his characterizations — even when he sets up some seemingly can’t-miss plot twists with secret lovers and a murder. I’m completely down for a wholesale evisceration of white capitalism. But your perspective has to be interesting and it has to work within the constructs of fiction. Andrés — the protagonist here — is a remarkably whiny fuck who is too enamored of schmaltzy cliches like “I am unsettled by the past.” He seeks peace by attending a twenty-year high school reunion, but his endless monologues felt too much like being trapped in a hotboxed van with some narcissistic twentysomething stoner rather than a married man hitting his forties. So this ended up being my least favorite book. It was the only National Book Award title that I threw against the wall. I even blasted the Beastie Boys as loud as possible as I did so to ensure that my fury was as authentic as possible. There’s no other way to say it: The Town of Babylon is one of the worst books of 2022.

8. Leigh Newman, Nobody Gets Out Alive

I’ve largely been happy with this year’s longlist, but I’m afraid that Leigh Newman’s short stories simply don’t cut the mustard. I really should have loved this collection. After all, it’s largely about struggling women in Alaska. But Newman, at least to my aesthetic sensibilities, is more of a nonfiction writer who has turned into a fiction writer. She doesn’t possess the verve or the knack for narrative momentum that you find in such brilliant small-town chroniclers as Elizabeth Strout and Stewart O’Nan. The more interesting details of her stories (why Alaskans need air conditioning, why the People Mover is used in October) are really the springboards for essays or journalism, not fiction. Many of these stories, such as “High Jinks,” are banalities that go nowhere. The strongest material in the book is “Howl Plaza,” “An Extravaganza in Two Acts,” and the second section of “Alcan, An Oral History” — all of which steer us into the inner observations of these hardscrabble characters with fine details. But even this work was still not strong enough to grab my heart. I really wanted to know more about these people! But when your deepest concerns are about how much salmon and cashews you’re scooping from the bottom of a bag on a trip, then I may as well just go to the bodega and listen to some dude tell me stuff like this in person. In short, Newman doesn’t have the music of a true storyteller. And I’m utterly baffled as to why the National Book Award judges picked this title for the longlist. Networking perhaps? That’s the only reason I can fathom.

Yes, it’s true! Only two miniature hit pieces from The Most Hated Man in PublishingTM! That’s how good the longlist is this year!

7. Ramona Emerson, Shutter

Holy frjole, folks! A crime novel made it onto the list! While it’s refreshing to see the National Book Award fiction judges be more inclusive of genre, I don’t think Shutter entirely sticks the landing. Ramona Emerson has a great feel for atmosphere and captures the shady feel of Albuquerque (and, in Emerson’s defense, she’s up against the inevitable Breaking Bad/Better Call Saul parallels). The novel does have an engaging premise: Rita Todacheen, an overworked Navajo photographer snaps crime scenes and has the ability to see the dead. The book alternates between Rita’s early life discovering photography with her grandmother (as well as contending with her increasing knack for yakking it up with the recently departed) and Rita in the present day — toiling every spare hour, not sleeping or eating, something of a ghost herself. But the internal affairs/police corruption subplot that Emerson tries to hang this book’s narrative momentum on is too generic and doesn’t quite work. Moreover, the investigator who talks with ghosts motif has been well played out by now. The Sixth Sense, The Frighteners, The Dead Files. I had hoped that Emerson would show more of how talking with the dead altered Rita’s character. After all, these ghosts are quite determined to talk with her (and the mechanisms that Rita employs to get some peace from these garrulous spirits are clever)! But I very much enjoyed Emerson’s writing voice. I just wish that this novel stretched genre a lot more than advertised.

6. Jonathan Escoffery, If I Survive You

This is an often dazzling, but by no means perfect interconnected short story collection about Jamaican immigrants on the run in Florida and the manipulative capitalistic forces that can turn anyone into a grifter. Escoffery has a good eye for the lowlifes who prey upon the poor and the vulnerable, as well as the personal circumstances that turn people into scammers. The best stories are “In Flux,” “Splashdown,” and “Independent Living,” which have solid and heartfelt observations about systemic injustice and that feel gritty and real. The remaining stories either get lost in the need to use the recurring character Delano to match everything or they just don’t land. But make no mistake: Jonathan Escoffery is a marvelous writer, a dude whose future work I plan to read eagerly. I do hope this is the beginning of a long career.

5. Gayl Jones, The Birdcatcher

Gayl Jones, as any literary person is well aware, is a legend. A neglected talent who deserves laurels and more. This is not quite on the level of Corregidora or Eva’s Man, but it is wild and fierce and stunningly original. We follow an erotica writer and the strange couple she hangs out with. The first 150 pages are breathtaking, questioning the nature of sanity and art and unafraid to tackle the truth of body disfigurement. But the novel starts to go off the rails with the third part, losing some energy and, with that vigor, much of the outlandish metaphors that make this book so original. But The Birdcatcher is still a wonderful read — even though, with all the references to Karl Malden and mercurochrome, it seems likely that this novel had been sitting in a drawer until Beacon rescued it. But I’m glad that this novel was published. It turns out that the world had to catch up to Gayl Jones’s fearless vision.

4. Marytza K. Rubio, Maria, Maria and Other Stories

Marytza K. Rubio is a fantastic writer! I love her imagination! This book reminded me of some of the more outlandish tales from Los Bros Hernandez. The more inventive and crazier that Rubio is, the more interesting she is as a writer. She crawls into interior lives and shakes up the short story form with the tenacity of someone determined to find the most unusual narrative entry point. There was only one story in this collection (“Moksha”) that struck me as somewhat conventional. But the rest? The rest! Oh, I enjoyed this book so much! The title story is a banger, as is the fascinating “Tunnels.” There is a concern for doubles, multiple identities, and, most intriguingly, black magic. Rubio is a tremendously exciting writer who caused me to walk through the Brooklyn streets with a goofy swagger that only a sui generis writer can summon. I’m very eager to read her future work.

3. Jamil Jan Kochai, The Haunting of Hajii Hotak and Other Stories

A total knockout! And if this stunning collection doesn’t make it into the finalists, it will be a literary injustice as great as Jakob Guanzon’s Abundance (a gritty masterpiece) being completely shut out last year. Kochai is just thirty years old, but he is talented as fuck! His stories are invaluable in the way that he provides perspective into the people of Afghanistan (as well as those who make their way to America). A story like “Occupational Hazards” would be gimmicky in other hands, given that it recontextualizes a man’s employment history. But Kochai somehow gets you to feel for this dude’s struggle within the form, thus superseding the trap of novelty. “Return to Sender” is a veritable horror story about a couple who receives their child’s body in pieces through the mail. While other writers would chomp at the bit for grisly shock value, Kochai is too careful and honorable a writer to do this. We truly feel the horror of this couple and it doesn’t come across as sensationalist. With these amazing tales, Kochai makes a compelling argument for keeping your eyes open and thinking beyond yourself. And he does this with an accomplishment that writers ten or fifteen years older than him have completely failed to master. I’m definitely keeping an eye on this kid. Like his fellow Sacramento writer William T. Vollmann, Kochai has the writing talent to get us to care about the souls who are rendered invisible by bourgeois scum.

2. Sarah Thankam Mathews, All This Could Be Different

If this great novel doesn’t make it to the finalists, I will go up to my rooftop, scream random obscenities, and shake my fist at the heavens! Sarah Thankam Matthews is a measured writer who will leave you in awe, both in what she reveals about her protagonist Sneha and what she leaves you to infer. (Is her nonbinary friend Tig using her? Or are they similarly troubled? These are the ambiguities that amount to great literature!) This is a character study of an Indian immigrant: queer, work authorization papers set to expire in two years, struggling to survive in Milwaukee. We see Sneha battle depression and anxiety. We see her suffer the indignities of an abusive downstairs neighbor who constantly complains. We see her ponder what love is with her girlfriend Marina. And we see her punished for making the very bold moves that the Sheryl Sandbergs of our world demand that we lean into. What makes Murphy such a terrific talent is the way she subtly depicts the forces of capitalism around us: what is unseen, what is known and unknown, and how everyone is only a few weeks away from making a desperate decision. And this tension is what sustains the narrative drive of this largely plotless novel. How can Sneha, who is so confident about declaring her salary to a mediocre man paid less than she is, be absolutely terrified of coming out to her parents? There’s one hilarious scene in a restaurant, in which Sneha is approached by an Indian mother who demands the phone number of her father, that really nails how one’s background is ineluctable no matter where you are in the world. There’s also a brilliant subtext here about how chasing your dreams (in this case, a commune idea called the Pink House) may not be a decision that is yours. When two cops cruelly pester Sneha and Tig near the end, we’re also reminded of the dangers of judging people. We’re all pinballs bouncing around in an infernal machine. But how do we live? And how do we not screw up? Or give up? I found this novel tremendously engaging and I came very much to care for Sneha and all her troubles.

1. Tess Gunty, The Rabbit Hutch

It was very difficult to decide between This Could Be Different and The Rabbit Hutch. I loved both novels with all of my heart. And both books are masterpieces. So I went for a four mile walk and carefully gauged the qualities of both books. And in the end, I had to stump for Tess Gunty. (Sarah Thankam Mathews, I am still greatly in awe of your work! I hope you don’t take it personally! I’m just one dude! Please write more books!) This is a novel that contains so many styles and angles on foster kids, abuse, social presumption, and the loneliness that so many people carry and that is neglected by others. Gunty writes with a kaleidoscopic eye about the fictitious Rust Belt town of Vacca Vale, Indiana — a doomed place denuded of industry and wonder, a town heavily populated by rats, a locale in which those who remain wonder what dreams they can still chase as they live in warrens. There’s even a sitcom television star reminiscent of Lucille Ball, wild comments sections on funeral parlor webpages, and supernatural insinuations. Above all, one is struck by just how batshit talented Tess Gunty is. Her prodigious dexterity on the page, which includes a chapter composed almost entirely of one sentence paragraphs, will undoubtedly annoy those who walked into this novel hoping for a straightforward story or even the alt-lit kids who seem to hate any title published by a major house. But even though I hate the editor of this book with every fiber of my being, I have to hand it to him. He likely got something more out of Gundy far more amazing than what was already there. If this book doesn’t make it to the National Book Award finalists, it will be a major insult to coruscating literary achievement.