I was 23 years old when I first spoke with Lucille Bliss over the phone. I was shy and uncertain and rudderless, toiling nine to whenever at a San Francisco law firm with two very friendly Russian women who laughed at my jokes. I was good at my job: good enough to earn the right to hit the second floor balcony every hour, taking seven minute breaks for the cigarettes I inhaled with the Plan B desperation of someone who wanted to be somewhere else.

I read fat books and scribbled doggerel into notebooks and worked an endless string of unpaid film shoots. I had no idea if I could ever earn money doing something I loved. In those thin-skinned days, I thought that I was a fairly reprehensible human being — in large part because people continued to suggest this. I was cursed with a mellifluous yet idiosyncratic voice that always seemed to offend someone and still does to this day, no matter how benign my intentions.

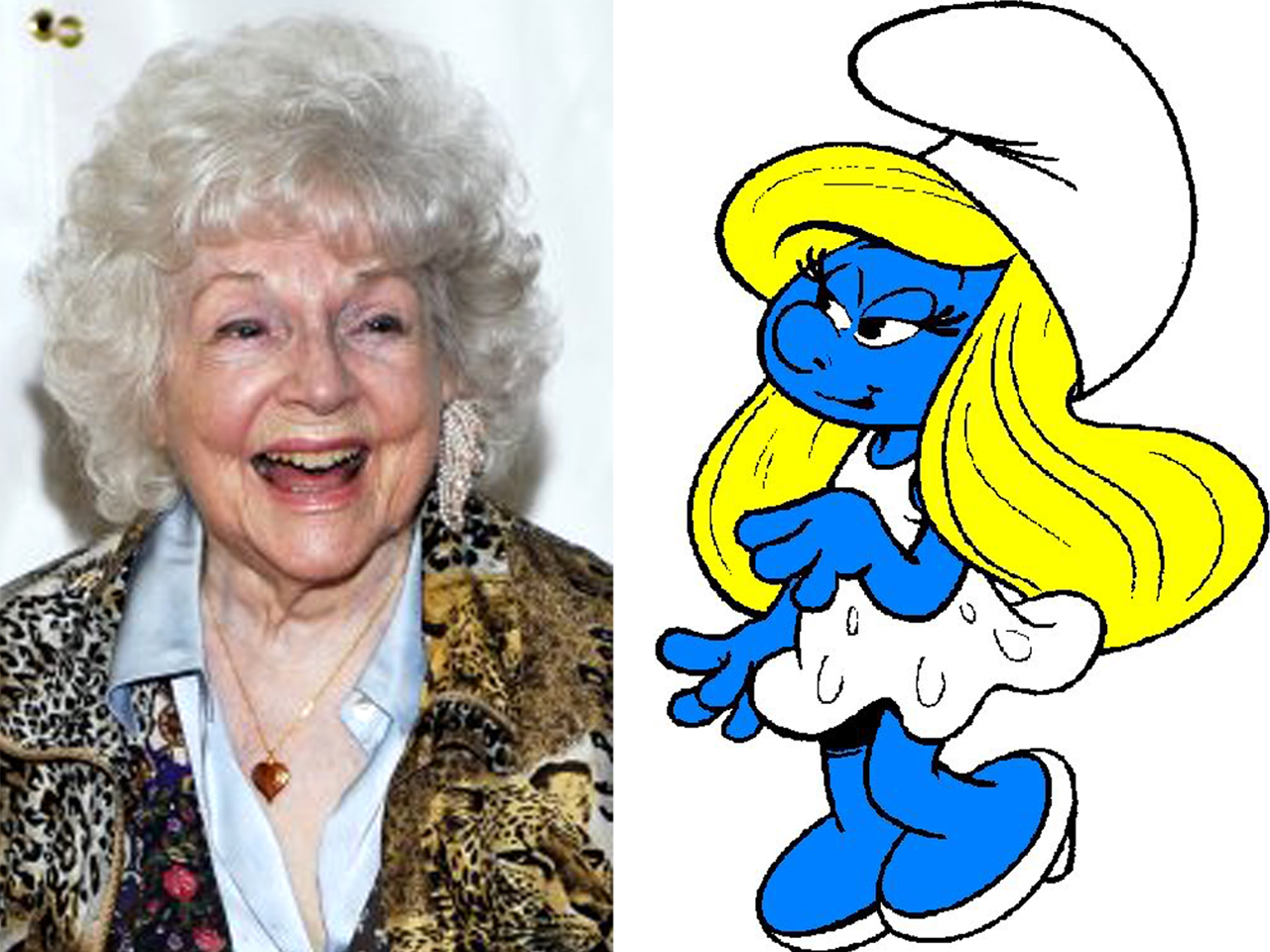

One morning, my day job duties required me to locate an audio facility to clean up a murky recording. Being an especially tenacious and thorough researcher, I located a recording studio that not only did the job very well, but that offered a surprisingly swift turnaround time. Because of this, I tried to throw them as much work as I could. The guy on the phone, perhaps sensing the vocal exuberance I would later put into The Bat Segundo Show, took a shine to me and asked if I was interested in voiceover. I said yes. He told me about Lucille Bliss, who I learned was the voice of Crusader Rabbit and Smurfette, and intimated that I should get in touch with her.

But I had no money at the time. I was still smarting from a vicious tax bill on the installment plan because of a previous employer’s scurrilous math. My extremely amicable roommate had moved out, leaving me with an additional share of the rent to pay. Did I want to learn from Lucille Bliss? Absolutely. But I had no financial cushion. I had no idea how much Ms. Bliss would charge. It would probably be astronomical.

I called the number that the guy had given me. A very kind and cheerful woman in her early eighties picked up. She asked me all sorts of questions. What did I want to do? Where had I gone to school? How long had I lived in San Francisco? I told her that I was thinking of going to this conference I had heard about called South by Southwest, but I wasn’t sure I could make it. “Oh, you should go!” she said. I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I couldn’t afford her lessons, especially when she told me later that she could teach me all sorts of ways to enhance my voice, which she called “amazing” after I had performed, with her quiet encouragement, an improvisation of a nervous squirrel seeking nuts in a park and an on-the-spot cheerful narration of a fictional documentary on Stalin, in which I recall making some especially bleak yet cheery jokes that made her laugh. We talked for hours. I never got the sense that Lucille’s main motivation was to sign up. She was more curious about who this young man was.

I concluded our conversation telling her that I’d think about voiceover. But I think Lucille had picked up on the fact that I was a dessicated husk when it came to money. I never thought I’d hear from her again.

But a few months later, Lucille called me out of the blue to see how I was doing. I was very apologetic. I told her how much I wanted to work from her, but intimated that I was still going through some financial difficulties. “Oh, that’s okay,” she said. “We all go through that.” But despite this, she talked with me for more than an hour. The one thing she said was that I should take any creative opportunity that came my way. I wasn’t sure what it was she sensed in me, but she was absolutely certain that I would go somewhere.

In hindsight, it seems strange to have received a much-needed confidence boost from Smurfette. I had never had a mentor. For most of my life, people looked to me as if I knew all the answers. Having someone as formidably talented and indelibly quirky as Lucille declare that I was capable of something more meant a good deal to me. And I took her advice. A few years later, I would go to war against my diffidence: working at magazines, writing and directing odd plays, talking my way into idiosyncratic gigs, dispensing quiet help where I could. If it hadn’t been for Lucille’s much needed words, I doubt that I would have taken as many chances as I have.

We don’t always know how our enthusiasm lifts another soul, but Lucille taught me that life is too short to stay silent.