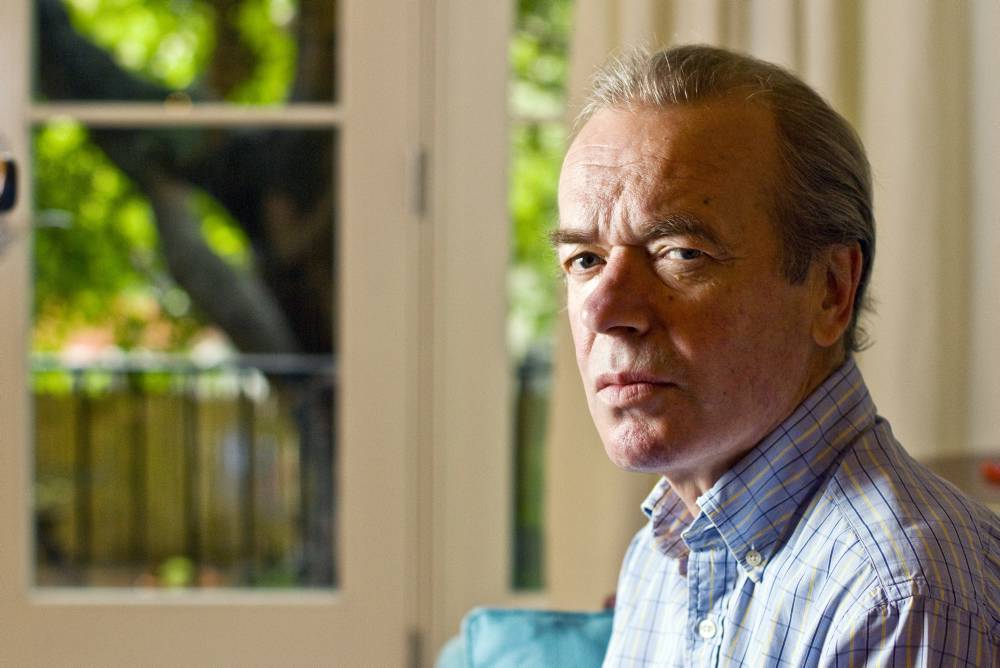

Martin Amis is most recently the author of Lionel Asbo. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #101.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 53:04 — 48.6MB)

This episode of The Bat Segundo Show is brought to you by Audible.com. If you want to listen to Martin Amis’s Lionel Asbo, and help keep this show going, sign up for a free audiobook and a 30 day trial. Use this handy link: http://www.audiblepodcast.com/bat

This episode of The Bat Segundo Show is brought to you by Audible.com. If you want to listen to Martin Amis’s Lionel Asbo, and help keep this show going, sign up for a free audiobook and a 30 day trial. Use this handy link: http://www.audiblepodcast.com/bat

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Seeking the filter of considered thought.

Author: Martin Amis

Subjects Discussed: How smoking prohibitions curtail sociopaths, Katie Price as fictional inspiration, reading the collected works of Jordan, whether Amis should be writing about the working class, class anxiety, living with a Welsh coal miner’s family, Amis’s views on class disappearing in England, the London riots, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, people shooting at each other during Black Friday, income inequality, physical deterioration in Amis’s novels, Lindsay Anderson’s if…, the male climacteric, Amis’s tendency to introduce incest with legal and moral codex, researching incest, “yokel wisdom,” New Labour and education, opportunism and rioting, Occupy Wall Street, police brutality, whether fiction can ever rectify social ills, Swift’s A Modest Proposal, Dickens, the video game medium, clarifying Amis’s stance and false rumors of shame about Invasion of the Space Invaders, being befuddled by remotes, addiction, being a Luddite, representing the present in fiction without including smartphones, going back in time as a novelist, Money and Amis’s lack of interest in New York, when nonfiction serves as a muse for fiction, pornography, masturbation, young people and sex, The Pregnant Widow, not fully understanding world events when writing The Second Plane, the massacre of the Sunni Muslims in Syria, social media, the camera as world policeman, Nabokov’s slogans, what provoked Amis’s impetuous words in a 2006 interview, Amis’s problematic remarks in interviews, lacking a filter, and writing as the ultimate intercession.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I do have to ask you about something. I’d like to talk about a medium that has a $65 billion global value, a medium that, in fact, was used by President Obama in 2008 to advertise for his presidential campaign, a medium that your friend Salman Rushdie has claimed in an interview to be “something of an Angry Birds master.” That medium, of course, is the video game. I do know, and I have to ask you this, that you wrote a book about Space Invaders. And I’m wondering. I did notice you have your pinball machine still. Why are you reluctant to own up to this Space Invaders volume? I’ve been really curious. I mean, it’s hard to find. You don’t want to talk about it. But I’m telling you that, in this age when video games are so omnipresent and have arguably outsized the movie, why would you be loath to talk about it?

Amis: I’m not necessarily loath to talk about it. I’m no longer interested in it. But there it is on my “By the Same Author” page. I haven’t disowned it.

Correspondent: But you haven’t exactly welcomed it back into print.

Amis: It hasn’t come up. I think in Italy, they’ll redo it. But that generation of games, that’s gone.

Correspondent: Not on the phones.

Amis: Not on the…?

Correspondent: Yeah. You can play Space Invaders on a phone.

Amis: Can you?

Correspondent: You can play Pac-Man on a phone. In fact, the interesting thing about some of these games is that they’re so universal and the technology is in a compact form. So you can actually use them. But what’s also impressive is, as I said, Obama actually advertised in game for 18 games in 2008 to reach voters. That’s how significant this is. And that’s why I’m curious why you have been, at least from what I’ve seen, reticent to grapple with the fact that video games are a massive part of our culture.

Amis: It’s because I’ve been left behind by all that. It’s all I can do to get a picture upon our digital TV.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Amis: I have to shout for one of my children to come and help me. I’m sort of all thumbs with all that right now and no longer interested in those slightly onanistic, solitary pursuits. But I’m as aware as everyone else is that that kind of — and I saw it with all my children that they went through years of not really wanting to do anything else. And I know how addictive they are.

Correspondent: They are very addictive. I had to uninstall some myself. That’s how bad they are. I had to read. When was the last time you played Space Invaders out of curiosity?

Amis: Not for twenty-five years. But what seems to be very addictive, my daughters admit to this, is that you do the first level and then you get on to the next level. And that kind of incremental building of skills to get to a new phase of the machine seems to be very deeply wired into us all.

Correspondent: So the addictive qualities really are why you have stayed away. Because you know that if you were to touch it again, you would actually get sucked in?

Amis: I don’t think so. I think I’m too Luddite now. I’m sort of anti-machines. And I get into a fury with things that don’t respond to what seems to me to be very simple instructions. Like the remote buttons on your TV. They’ve succumbed to what they call feature creep, where they just pile on the extras until it’s unusable by someone who isn’t prepared to really enter into it. So that part of my life is just sort of dead. And I couldn’t imagine getting interested, let alone addicted, to that anymore.

Correspondent: But what about, for example, Lionel Asbo? You conveniently have an area of Diston where somehow there are no iPhones really. There’s a Mac at the very beginning, but the sounds that we hear are natural shouts, as you are careful to note. The book goes into 2013 and really doesn’t wrestle with the fact that, if you go outside, people are looking down at their phones. They’re taking pictures of everything. They’re documenting every minutiae. And I’m wondering if you’re ever going to grapple with the reality of social media and just the sheer compact technological hold, the hold that compact technology has upon our lives.

Amis: My father said at one point. He said the reason you writers hate younger writers is that younger writers are telling them — they’re saying to the older writer, “It’s not like that anymore. It’s like this.” And it’s painful not to be on the crest of modernity as you were when you were younger. It’s not that you’re hankering for anything that’s gone. It’s not a reactionary things. It’s a helpless exclusion, really, from things you no longer understand and don’t want to make the effort to understand. Though I’m sure there are many able writers who are going to do what is there to be done with that subject, social media. But it’s not me.

Correspondent: You’re on safe ground when you go back to 1970 or, with your next book that you’re working on, back to the 1940s. Is going back in time your solution to this problem? I mean, the bona-fide literary high standards type will basically say, “Well, it’s the writer’s duty to completely submerge himself into our present day culture. And if that means something as often obnoxious as social media or phones, that’s part of the deal, bub.”

Amis: Writers are under no obligation to do anything whatever. Nabokov said — well, he was perhaps a bit prescriptive the other way.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Amis: But he said, “I have absolutely no interest in these subjects that bubble up and in a year or two will resemble bloated topicalities.” He said, “My stuff is not interested in the spume on the surface of things.” That he’s looking underneath the surface. I don’t feel that I’m being at all neglectful in not finding out about social media. It’s not a subject that excites me.

Correspondent: What about — you did explore New York, especially areas of Manhattan in Money. You’re now in Brooklyn. Do you have any interest in exploring our interestingly gentrifying areas around here?

Amis: Beyond a certain point, I don’t think where you are makes much difference at all. We lived in Uruguay for three years in 2003 to 2006. And I was often asked if I intended to do anything with Uruguay in fiction. And I can imagine writing a paragraph or two about it. But you get the feeling, rightly or wrongly, that after a certain age that you’re locked into your own evolution as a writer and that the things that you’re writing about now have been gurgling away inside you for a long time. And the idea of having a sort of hectic response to what happened yesterday seems very odd to me now and distant from me.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 53:04 — 48.6MB)

Love this interview Ed- I’m glad I’m not the only one who has to ask their children to turn on the TV.