Louis Hyman appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #443. He is most recently the author of Borrow.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering why the banks don’t cut him off like the bartenders do.

Author: Louis Hyman

Subjects Discussed: How common American notions of cash and credit shifted in less than a hundred years, an alarming Freddie Mac ad involving magical gnomes, the history of mortgages, the 1930s mortgage crisis, mortgage-backed securities, whether American citizens can be held responsible for permitting corporations to seize control of the financial system, Jack Welch’s mass firing of employees and restructuring of GE, why the postwar economy was prosperous on credit, middle-class aspirations, top tax rates throughout American history, the reasonableness of a 91% tax rate on the wealthy, the rise of discount stores in the 1960s, the beginnings of Kmart and Target, Macy’s early resistance to credit, the inability to fight the revolving credit system during the 1960s, how specialty stores like Ann Taylor catered to the middle-class, why credit cards became necessary for the newly distributed economy in the 1960s, department store credit and credit cards, the beginnings of Master Charge (later Mastercard) and BankAmericard (later VISA), how the need to dress up if you wanted to go to a department store in 1961 helped encourage the rise of the discount store, the early cash-only success of The Gap in the 1970s through computer inventory, why college students should not have credit cards, how the Maruqette Supreme Court decision paved the way for credit cards, the near total decimation of anti-usury laws, the Constitution’s commerce clause, RICO, why Congress is reluctant to protect consumers, how South Dakota became the center for finance, market regulation, protecting consumers from bad decisions, the inability for most people to do the math on exorbitant credit rates, working people who become reliant upon credit cards, living paycheck to paycheck, William H. Whyte and budgetism, the difficulty of introducing regulatory mechanisms when so many people believe in unfettered personal responsibility, the creation of the Federal Housing Authority, the housing battle between James A. Moffett and Harold Ickes in the 1930s, marshaling the business class to fulfill social ends, Henry Ford’s opposition to the extension of credit, Ford vs. GMAC in the early days of auto loans, regulation and property rights, the duty CEOs say they have to maximize profit for their shareholders, Jack Welch’s invented heroism, investing pension in the right areas, the rise of the aerospace industry, the Chicago debacle of 1966 where bankers flooded the market with credit cards without thinking, the beginnings of FICO, desperate efforts by bankers to make banks exciting, John Reed risking his career at Citibank on credit cards, Joseph Miraglia‘s pioneering efforts to scam the credit card industry, the present social stigma on using cash instead of credit, credit cards and securitization, the savings and loans crisis, fair and transparent forms of securitization, why Murray’s Cheese can’t get a bank loan, and acceptable forms of Wall Street wizardry.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

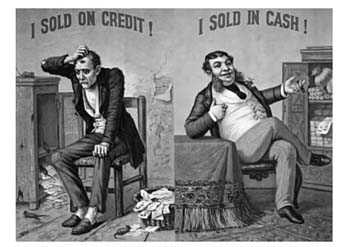

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture.

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture.

Hyman: As well they should.

Correspondent: So why were people willing to believe in gnomes? Is it possible for you to explain in plain English what in the hell a CMO is? And why did Freddie Mac even need a new financial instrument? Just to get this party started.

Hyman: Well, that’s about fifteen different questions.

Correspondent: Yes!

Hyman: I will start with the most important question.

Correspondent: Okay.

Hyman: Which is why did people want to put money into these mysterious supernatural instruments.

Correspondent: Gnomes!

Hyman: Yeah. Only the gnomes know. It’s hard to describe it over the radio. But it’s an image of gnomes advising the head chief financial officer of Freddie Mac and saying even he does not understand how these things work. Only gnomes know. It’s terrifying to comprehend that no one understood what they were doing. But the truth of the matter was that they knew what they were doing in that what they thought that they were doing. What they thought they were doing was taking together a bunch of risky things, combining it in different ways using magical alchemical transformations, and in the process they thought they were reducing the overall level of risk. And then they were making those sellable in the form of bonds to people who ordinarily would not buy them. To understand this, you need to understand the back history of mortgages and how they were financed and sold in America, which I’m very happy to talk about.

Correspondent: Feel free!

Hyman: And it’s what I talk about in the book before the time of the gnome hegemony.

Correspondent: Pre-gnome. More level-headed times.

Hyman: Yeah. Before the dwarven under kingdom began to rule us in the night.

Correspondent: Before investment bankers cleaved to the Return of the King appendix and started speaking in Elvic langauge.

Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?

Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?

So with mortgages, the story is a long one. And I’ll spare you the details. Though in the book, the details are quite intriguing, I hope. The basic idea is that, before the 1930s, you could get a mortgage from a local bank. They were very expensive and they tended to be funded by — they were balloon mortgages like we have today. We imagine that they were recent inventions. But they actually were commonplace in the 1920s. And they fueled the housing boom. Because they allowed people to pay only the interest every month on their mortgage. Which meant that they could buy more of a house. And the banks, in turn, would resell little bonds, mortgage bonds, to pay for all those mortgages going out. And so we have something like the mortgage-backed security is today. And with all that money from the investors, they could then lend to all these people to buy. Now the problem was, of course, that as soon as the stock market crash happened, all those panicked bonds people stopped buying bonds. All those panicked investors stopped buying bonds. And then suddenly the banks ran out of money to lend for mortgages and those balloon mortgages all came due.

Correspondent: We’re talking about the mortgage-backed securities period with the participation certificates.

Hyman: They were called participation certificates. That’s the technical term from the 1920s. And what happens is that suddenly they had to foreclose on all these houses and you have the housing crash of the Great Depression. It wasn’t because people lost their jobs as much as they lost their investors. Which I think is a really counterintuitive finding from what we think about when we think about the Great Depression. And so after this, the government creates the FHA. And the FHA and Fannie Mae together, what they do is they say, “Look, little bank. You can lend money to this home buyer. And then we will sell it to distant investors. Like in New York City.” So insurance companies, for the most part, bought these mortgages whole. The entirety of them. And then that money can be used to pay for a house in Texas. But these kinds of bonds, which fueled this wild, crazy, free-for-all kind of atmosphere in the 1920s — those went out of style. Investors didn’t want to buy them. Because they had all gone toxic. And the Fed actually prevented banks from using them at all. And so this period from the ’30s to the ’70s, they’re outside. They’re no longer in our economy. But the problem is that if you want to get more money into the housing market, you want people to have more money to invest in houses like they did in the late ’60s and early ’70s — predominantly to fund housing of the poor.

Correspondent: Section 235.

Hyman: Section 235. Correct. It’s as if you read a book recently on the topic.

Correspondent: Your book perhaps!

Hyman: Perhaps a book I am acquainted with. This money was to be used for that. And it was because they confused the cause for the effect in the postwar period. They looked around them. They saw on the one hand impoverished cities and, on the other hand, prosperous suburbs. And they thought, “Well, let’s make the cities like the suburbs.” And instead of realizing that the reason why the suburbs were prosperous was because of all the jobs that the well-to-do white people had, that made them prosperous, they thought, “Oh, it was just because of their houses.” They confused cause for effect. And they created this program to bring back the mortgage-backed security, which then these bonds could be sold to new kinds of investors. Not just insurance companies, but pension funds. To all kinds of people. And actually to these small banks, it turns out. They turned out to be the biggest buyers initially of these mortgage-backed securities. And so what you have is this system which actually collapses in a year or two under George Romney’s administration of the Housing and Urban Development. But the mortgage-backed security survives and becomes the new basis for our economy.

Correspondent: And they also use the term “participation certificate,” leaving one to wonder — at least this reader to wonder — why they would use the same name of a clearly failed idea.

Hyman: It had been several generations. And so they were vaguely…

Correspondent: People forget.

Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.

Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.

Correspondent: Just as the participation certificates worked fine until things started to happen.

Hyman: Until things fall apart. Things work fine until they fall apart. That’s how it is. You survive every accident you have until the one that kills you.

Correspondent: So why do these financial people, who should know this — because the historical examples repeat and repeat and repeat — why are they so short-term in their thinking when they consider credit ideas or debt ideas? Or even the extension of credit? I mean, this is what gets me. That nobody seems to have a memory longer than a few years. It’s like, “We’ve got some money! We’ll go ahead and blow it!” I’ll get into the hilarious Chicago credit card thing in a bit, which I thought was funny. But also remarkably short-sighted.

Hyman: No. It is really surprising. I think people are just intoxicated by reason. They think that if a model works, then it will work in the real world too. But the way things work on the ground and the way things ought to work can be quite different. And I think that’s one of the lessons of all of this. That we should trust our experience more than our thinking on some level. Our thinking can be wildly off. Everything made sense. But when you look at the models that people actually use for all this kind of lending, they only use three or five years of data. They don’t even use a full business cycle. And they did that because that was the data that they had.

Correspondent: Well, I guess the question here is: we are looking at this from the vantage point of financial people. The question I have is whether American citizens can be held accountable for some of the problems that occurred. To what degree should they be held responsible for borrowing, believing, going ahead and taking the extension of credit options that were given to them so that they could live their middle-class lifestyles? Does historical precedent reveal that our parents and our grandparents are victims of various strains of predatory lending? Or is it really these middle-class aspirations? How do we look at this?

Hyman: Our grandparents lucked out. So if you look at the actual Federal Reserve data, you see that people began to borrow like crazy after World War II. But what was different was that they actually had good jobs. And they were able to pay back all those debts. So the amount of borrowing goes up. But so does the amount of repayment. So it looks like no one’s borrowing.

Correspondent: Sure.

Hyman: But they’re actually using car payments for their big-finned cars. They’re using mortgages for the suburban housing. They’re using charge-a-plates at the mall. They’re doing all kinds of things that require debt. Now are they better people than us? No, they just live in a different time. So that today, it’s very difficult to have the same job over your entire life. That kind of job security is no more. Wages have stagnated for forty years for average people. And people get sick. They lose their job. And they’re stuck with these bills. So they have credit cards to fall back on. Though I don’t think it’s the people who have gotten dumb or become immoral. I think it’s that the world around them has changed.

Correspondent: But when one considers such transitions as Jack Welch’s decision to move GE’s resources from manufacturing capital to financial capital, and essentially eliminate jobs that give people money that allow them to purchase goods that allow them to perpetuate an economy, the question is…

Hyman: Are we responsible for that?

Correspondent: Are we responsible for that?

Hyman: Yeah. I think on some level we were fools to let this happen.

The Bat Segundo Show #443: Louis Hyman (Download MP3)