Porochista Khakpour is most recently the author of The Last Illusion. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #249.

Author: Porochista Khakpour

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Lyme disease, the thrill of not knowing yourself, messy house syndrome, bird mythologies attached to various nations, Marco Polo and the roc, drawing from the Shahnameh, the inspirational value in Googling feral children, what artists talk about on smoke breaks, when readers hold an author morally responsible for fictitious animal abuse, BASE jumping, the Freedom Tower video, going blonde for Elle, making lunch with caviar and Wonder bread, being a white demon in a dark world, Toni Morrison’s advice on writing the book inside you (with mangled paraphrasing), being obsessed with Latin American and surrealistic writers, the appeal of the grotesque, being young and adversarial, when novels become unanticipated memoirs, when the “unreal” is more real than real, David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest, Karl Ove Knausgaard, hard realism vs. surrealism, Stephen Dixon, hyperrealism, when realism becomes too polished or manicured, dry literary modes getting in the way of depicting reality, Carol Shields, harmful MFA diets, James Salter, Richard Yates, John Cheever, academics who misinterpret authenticity, finding the human in the idiosyncratic, the freaks, and the outsiders, why Bret Easton Ellis’s work is dismissed, Glamorama as an underrated novel, Khakpour’s review of Helen Oyeyemi’s Boy, Snow, Bird, the myth of perfect novels, why risks and originality are important to sustaining unique fiction, attempting to track what went wrong with risky American fiction during the last twenty years, the dangers of likable books, Dinaw Mengestu’s All Our Names, Yiyun Li’s Kinder Than Solitude, why young American readers are so conservative, millennials who avoid politics and history, when reading choices are impacted by economic crisis, what happens when the youth experience of bouncing around jobs is taken away from American life, needless obsessions with “being good,” when favoriting and liking intrudes upon the sincerity of genuine compliments, why hierarchies now look stupid, ridiculous formalism vs. overly casual forms of address, speed and anxiety, the threat of phones that entice us with buzzing notifications, contemporary anxieties over art that confronts, the remarkable human capacity for inventing needless popularity contests, being part of an immigrant group and fitting in, being true to yourself, ridiculous calculations set up by publishers, when New York publishing types forget regular readers who crave something different, why women’s magazines have embraced The Last Illusion, doing something daring because the universe is indifferent, blind ideological labels that cause nuance to be overlooked, “TWITTER NEVER FORGETS”, suspicion attached to sincerity, the apology cycle, media training’s assault on the real, healthy anti-authoritarian impulses, illegal methods of making money, the trap of fancy restaurants, the mistaken assumption that all writers live middle-class lifestyles, consumerist impulses that get in the way of the writing life, the appeal of New York City (when one can barely afford it), being exposed to subcultures, finding places where outsiders are accepted, Y2K and 9/11 as efforts to destroy New York, New York’s openness, medical arbiters named after guitar gods, how storytelling can combat injurious forces against the individual, inhabiting your own narrative, adopting a uniform of neon orange socks and a cowboy hat for school, pranks as a form of existence, prank phone calls, dialing up a radio station and pretending to be other people, talking in a baby voice as a professed Playboy Playmate, testing the notions of what people are willing to believe, learning international calling codes as a child and asking people in Nairobi to speak Swahili, physically digging holes to China, being paralyzed by knowing we’re going to die, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, getting the big death questions out of the way on the first date, the benefits of not caring vs. paralyzing thoughts as a kid, dramatizing how people believe in illusions, betrayal and panic attacks, differing emotions that emerge from PTSD and betrayal, fear and illusion, magical thinking, the Y2K panic in San Francisco, Y2K as a cultural embarrassment, failing to consider American time before 9/11, Asiya perceived as a villain in The Last Illusion, why a 500 pound character is the soul of The Last Illusion, eating insects (and associated ethics), being inspired by paintings, how different generations have viewed women, the absence of parents, family structure as a safeguard against feral children, destructive ways of being to survive a fractious childhood, Kafka’s response to Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, Kafka’s notion of the other Abraham as a solution to the parable’s heroic failings, father figures as impostors, having a checkered employment history, work as an enslavement of faith, saturating a novel with pre-9/11 paraphernalia, celebrating the autodidact, awkward paths to manhood, masturbation, connections between reading fiction and empathy, how online skimming is discouraging people from reading ambitious fiction, how to get more people to read Ulysses, trends in longform, the recent fetishization of Gay Talese, Renata Adler’s resurgence among young people, the double-edged sword of “legitimized” indie presses, marketing savvy entering into alt lit considerations, hostility towards works of ambitious fiction, Rebecca Curtis’s stories, Leslie Jamison, the impact of the VIDA Count, trying to get young men to read, reading around the world to atone for American literary inadequacies, Borges’s Ficciones, and hopes expressed for future punks.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Khakpour: I’ve got gallows humor for miles, but I’ve been having so many difficulties because of a recent relapse of Lyme disease. So I’m finding everything a little extra challenging. But maybe also a little bit thrilling. Because who knows what will come out?

Correspondent: What’s the thrill of this predicament?

Khakpour: The thrill is that I actually don’t entirely know myself. And so…

Correspondent: You’ve found out more things about yourself.

Khakpour: (laughs) Well, sort of. I’ve been teaching and lecturing and sometimes I feel like this disease attacks your softer tissue. Everywhere. Your brain and your organs and everything. At certain times…

Correspondent: I thought that the brain was a harder tissue. All that work. Especially your brain.

Khakpour: In my case…

Correspondent: No.

Khakpour: …it’s pretty dim.

Correspondent: Oh, I don’t know about that.

Khakpour: It’s weird. I remember certain things that I thought I had done away with and then certain things I will completely forget. You know, I have that sort of senile dementia.

Correspondent: But, see, I’m like that without Lyme disease.

Khakpour: (laughs)

Correspondent: So I think actually, if that’s the case, you’re the most formidable intellect who has ever appeared on this show.

Khakpour: (laughs) Thank you. It’s amazing. I looked up this thing called messy house syndrome.

Correspondent: Messy house syndrome!

Khakpour: And I thought that it literally just meant, “Your house is messy.”

Correspondent: Or your house is not in order. In some family dynasty sense.

Khakpour: (laughs) I think it’s this thing. I’m not sure exactly how to pronounce it. There are various names that involve forms of senile dementia that are related to it. And it is an interesting umbrella term for various forms of cognitive dysfunction that I very much relate to. But I don’t think it’s permanent. I hope it’s not permanent. I’m enjoying it a little bit. My emotional range is quite stunted.

Correspondent: It’s kind of a temporary vacation from possibly thinking all the time.

Khakpour: Well, I’ve short circuited a lot with thinking.

Correspondent: Well, you’re associative, I think.

Khakpour: (laughs) Exactly.

Correspondent: Which some people call a short circuit, but actually is really kind of liberating. So you have this little caesura in the usual great Porochista universe.

Khakpour: It’s interesting. I used to be so obsessed with altered states and I would do drugs to achieve them and all that.

Correspondent: Now you’ve got the ultimate altered state. The ultimate natural high.

Khakpour: Exactly. So in some ways, it’s kind of amazing. But it would be nice if I knew it would end soon. I think it will.

Correspondent: And yet you have been nothing less than perspicacious so far.

Khakpour: Okay. Thank you. Phew. (laughs)

Correspondent: Let’s get into the book. So Marco Polo, he popularized the legend of the roc. The Greeks, they have the phoenix. Slavic folklore has the firebird. In short, I don’t think there’s a single culture in the world that does not have some form of a mythological bird. America has the bald ego…the bald eagle. The bald ego as well! (laughs)

Khakpour: (laughs) The bald ego as well! I was going to say.

Correspondent: The bald ego and the bald eagle. And not far from the years of your novel, in 1999 to 2001, which is when yours is set, the bald eagle was actually placed from an endangered species to a threatened species and now is actually off that list altogether. Because the bald eagle made a comeback. So beyond your inspiration from the Shahnameh, I’m curious what drew you to the bird as this malleable mythological symbol. To what extent were you interested in not only transcending culture across nations, but even subcultures, perhaps bird-related, within this nation?

Khakpour: Oh. That’s so interesting. I love that question. Yeah. There’s a lot of avian themes in everything I write. It’s strange. It was in my first novel as well. And then I just naturally gravitated toward it here. I was at a residency where everybody was working very hard. And it was one of my first residencies. And I had no interest in being there almost. I was just tired from the first book. And I just decided I was going to read during my residency time. I brought a copy of the Persian Book of Kings, the Shahnameh, the Dick Davis translation that came out a few years ago. And I was flipping through it and remembering my father reading it to me in Farsi. And there was always just this one story that I always would make him reread. And it was the story of Zal and his friendship with this giant mythological bird, the Simorgh. It’s strange to even say “friendship.” I mean, the Simorgh was this guardian. And so essentially raised him. So anyways, that was in the back of my mind. While I was flipping through it at night in this residency, I would go on smoking breaks and there was this one other lovely artist there who was the only other smoker and she was also kind of pretending to do work. And we would just talk about our lives during these smoking breaks. And one time she said to me, she would just go on these rants and she said, “Whatever you do, never Google ‘feral children.'” And I said, “Wait! Why did you say that? What?” And she said, “Oh no. I’ve just been bored. I’ve been Googling things late at night.”

Correspondent: As one does.

Khakpour: Yeah. And then so I thought, “Okay.” I went there obviously. It was late at night there one night. And it was very horrific. And I’d always been interested in both the “reality,” but also the hoaxes that have been attributed to feral children. So then I found this case, this Russian case, of a bird boy who’d been essentially partially raised in a cage and could only chirp. Maybe it was a hoax. Maybe not. And immediately I combined that with Zal in my brain. And the two just kind of mashed up seamlessly. The next day at our smoking break, I told her. I said, “I think you just helped me come up with my second novel.” I’d had the other thread of the second novel, which really involved the magician and the last illusion. But he was only — I could always tell that he was 50% most of the story. There was a whole other thread. So I don’t know. Then I came to that and it was actually interesting. I came to realize, “Boy, you’re obsessed with birds and flight and all that. What is that about?” And there’s a made up myth in the first novel that involves burning doves actually. It’s sort of the myth behind the narrative of the first novel.

Correspondent: This is what it sounds like when the doves fry.

Khakpour: (laughs) Yeah.

Correspondent: Sorry.

Khakpour: So many people scold me about that scene. It’s funny. People come to the readings. And I only started reading from it late in the game. And I would have these oftentimes older women who would come to me and say…

Correspondent: Older women?

Khakpour: Yes. Who’d say, “Why would you have such scenes of animal abuse?” And they would accuse me of having harmed animals myself. And I was just so horrified. I was, “No, this is fiction.”

Correspondent: People get very sensitive to animals being harmed in fiction, I find.

Khakpour: Totally.

Correspondent: I mean, they are more willing to impugn an author for a fictional animal abuse more so than any real animal abuse.

Khakpour: I know.

Correspondent: It’s really odd.

Khakpour: Incredibly. I know. And people were very disturbed by that. But anyways, you brought up so many good points about the cultures in the U.S. too. I think, I mean, there’s a general awe that comes when you think about flight, right? It’s one thing we definitely can’t do. We can do it in these wonky adorable human ways. Hang glider. Sky diving.

Correspondent: BASE jumping.

Khakpour: Yeah, BASE jumping. Right.

Correspondent: That amazing video from the Freedom Tower.

Khakpour: I know.

Correspondent: I’m not even going to tell you how many times I saw it.

Khakpour: Same here.

Correspondent: It just gave me such a cathartic thrill.

Khakpour: Oh yeah. I started collecting a lot of those ideas, or collecting a lot of those instances and looking at their videos and all that, when I was writing this. And that figures — even the idea of stunts that involve flight or falling — big in this book.

Correspondent: How many times did your dad read you the legend of Zal? I’m curious. Because this seems to me that it was deeply imprinted upon you as a child.

Khakpour: Yeah.

Correspondent: And we always go back to the tales we’re told as children to find meaning and inspiration as adults.

Khakpour: Over and over, I would ask him to read this. He would keep going. There’s many amazing stories in the Shahnameh. There’s so many beautiful and incredible — you know, it has that feeling of The Canterbury Tales and The Old Testament where you can go to it for unlimited inspiration. But I was frozen on Zal. I related to him so much. Because there was also — you know, in my first novel, there’s a whole thing with I Dream of Jeannie. This blonde genie and the weirdness of that to me.

Correspondent: And here you are blonde as well. (laughs)

Khakpour: Yes. For an article.

Correspondent: It was in the prophecy! (laughs)

Khakpour: Yes. Exactly! Now I am one of the fakest blondes ever. So that was a fascination. The other thing that was interesting in the story of Zal was that he was born essentially something like an albino. It’s unclear from the text exactly what they meant. But he had a certain whiteness of skin and a lightness of hair. He basically had white hair. And that was why he was cast out. And I think for an Iranian immigrant new to the U.S. — at that point, we’d only been a few years in the U.S. — I was so fascinated by issues that surrounded race and ethnicity in the U.S. vs. Iran and what that all meant. So Zal to me was just — I didn’t know what to make out of this story. He was somehow what Americans might consider the ideal of beauty. Maybe even some other cultures of course. And yet he was cast aside. Basically left in the wilderness to be raised by a bird.

Correspondent: There were a lot of uncleared mysteries in the original tale.

Khakpour: Yeah.

Correspondent: And maybe this is perhaps what captured your imagination and led you to flesh it out and transplant it here in New York.

Khakpour: Exactly. Yeah. And I had been so anxious about fitting into America at that point. And I knew — I couldn’t even really relate to my own parents. I mean, they were of a different socioeconomic class than my brother and I. So here were two upper-class Iranians in their twenties who were fairly gutted about not being able to do fancy things. You know, my mother would be upset that we couldn’t have a childhood where we went shopping in Europe. And my father was meanwhile making us only Wonder bread sandwiches with butter and caviar on it.

Correspondent: Butter and caviar?

Khakpour: (laughs) Yeah.

Correspondent: Wow. That would make the lunch trade a little bit more convoluted.

Khakpour: (laughs)

Correspondent: “I’ll give you the caviar for the apple.”

Khakpour: (laughs Yeah. Exactly. It was a very confused issue concerning nationality and ethnicity and all that.

Correspondent: And class.

Khakpour: And class. Definitely. So I was constantly thinking about this. And when I would get tired, late at night, when he would read me these stories, I’d have horrible insomnia. I would sit with him and he’d pick up where he left off. I would just ask him, “Could you read this story one more time?” He seemed to give me both a combination of hope for the outsider — because at the end of the Zal story, he’s a great warrior and he’s a great hero of the Persian Empire. And even his whiteness starts to be discussed as silver. It’s very striking. He suddenly becomes the embodiment of strength and power. But there’s a lot of conflict in this story too. And there’s a lot of darkness in that story too. And that really got my wheels turning at a young age. And I feel like I’ve always waited to have an opportunity to do something with that story. And it sort of got me when I didn’t even know that I was looking for it.

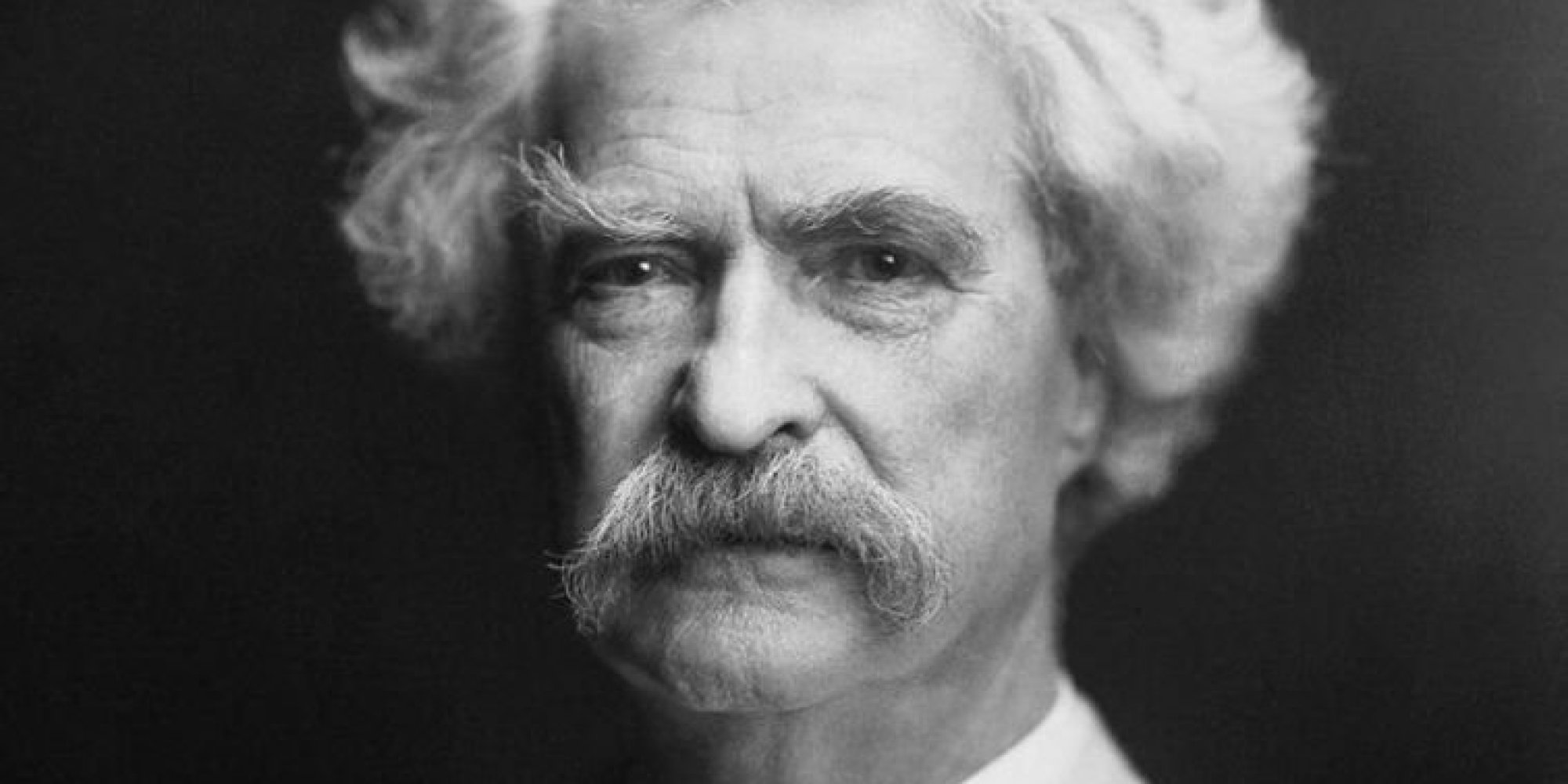

(Photo: Darcy Rogers)

(Music provided through Free Music Archive: Jose Travieso’s “Zombie Nation.”)

The Bat Segundo Show #545: Porochista Khakpour II (Download MP3)