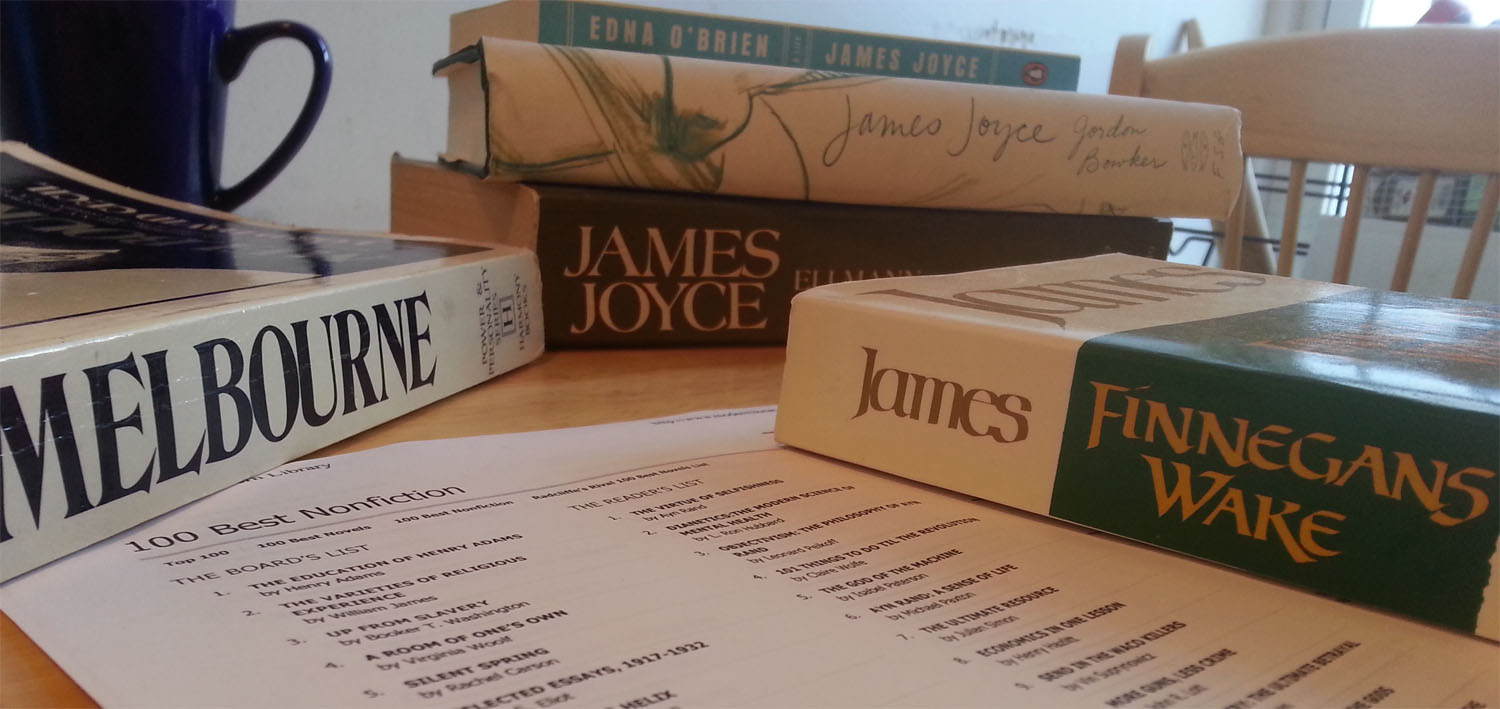

(This is the second entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: Melbourne.)

It is easy to forget, as brave women document their battles with cancer and callous columnists bully them for their candor, that our online confessional age didn’t exist twenty years ago. I suspect this collective amnesia is one of the reasons why Anne Lamott’s Operating Instructions — almost an urtext for mommy blogs and much of the chick lit that followed — has been needlessly neglected by snobbish highbrow types, even when hungry young writers rushed to claim transgressive land in the Oklahoma LiveJournal Run of 2006.

It is easy to forget, as brave women document their battles with cancer and callous columnists bully them for their candor, that our online confessional age didn’t exist twenty years ago. I suspect this collective amnesia is one of the reasons why Anne Lamott’s Operating Instructions — almost an urtext for mommy blogs and much of the chick lit that followed — has been needlessly neglected by snobbish highbrow types, even when hungry young writers rushed to claim transgressive land in the Oklahoma LiveJournal Run of 2006.

Lamott’s book, which is a series of honed journal entries penned from the birth of her son Sam to his first birthday, was ignored by the New York Times Book Review upon its release in 1993 (although Ruth Reichl interviewed her for the Home & Garden section after the book, labeled “an eccentric baby manual” by Reichl, became a bestseller). Since then, aside from its distinguished inclusion on the Modern Library list, it has not registered a blip among those who profess to reach upward. Yet if we can accept Karl Ove Knausgaard’s honesty about fatherhood in the second volume of his extraordinary autobiographical novel, My Struggle, why then do we not honor Anne Lamott? It is true that, like Woody Allen in late career, Lamott has put out a few too many titles. It is also true that she attracts a large reading audience, a sin as unpardonable to hoity-toity gasbags as a man of the hoi polloi leaving the toilet seat up. Much as the strengths of Jennifer Weiner’s fiction are often dwarfed by her quest for superfluous respect, Anne Lamott’s acumen for sculpting the familiar through smart and lively prose doesn’t always get the credit it deserves.

Operating Instructions — with its breezy pace, its populist humor, and its naked sincerity — feels at first to be a well-honed machine guaranteed to attract a crowd of likeminded readers. But once you start looking under the hood, you begin to understand how careful Lamott is with what she doesn’t reveal. It begins with the new baby’s name. We are informed that Samuel John Stephen Lamott’s name has been forged from Lamott’s brothers, John and Steve. But where does the name Samuel come from? And why is Lamott determined to see Sams everywhere? (A one-armed Sam, the son of a friend named Sam, et al.) There are murky details about Sam’s father, who flits in and out of the narrative like some sinister figure with a twirling moustache. He is six foot four and two hundred pounds. He is in his mid-fifties, an older man who Lamott had a fling with. We learn later in the book that he “filed court papers today saying that we never fucked and that he therefore cannot be the father.” Even so, what’s his side of the story?

This leaves Lamott, struggling for cash and succor, raising Sam on her own with a dependable “pit crew” of friends. Yet one is fascinated not only by Lamott’s unshakable belief that she will remain a single parent for the rest of her natural life (“there is nothing I can do or say that will change the fact that his father chooses not to be his father. I can’t give him a dad, I can’t give him a nuclear family”), but by how the absence of this unnamed father causes her to dwell on her own father’s final days.

Lamott’s father was a writer who “died right as I crossed the threshold into publication.” His brain cancer was so bad that he could barely function in his final days. Lamott describes leaving her father in the car with a candy bar as she hits the bank. Her father escapes the car, becoming a “crazy old man pass[ing] by, his face smeared with chocolate, his blue jeans hanging down in back so you could see at least two inches of his butt, like a little boy’s.” It is a horrifying image of a man Lamott looked up to regressing into childhood before the grave, leaving one to wonder if this has ravaged Lamott’s view of men — especially since she repeatedly chides the apparent male relish of peeing standing up — and what idea of manhood she will pass along to her growing boy.

Part of me loves and respects men so desperately, and part of me thinks they are so embarrassingly incompetent at life and in love. You have to teach them the very basics of emotional literacy. You have to teach them how to be there for you, and part of me feels tender toward them and gentle, and part of me is so afraid of them, afraid of any more violation. I want to clean out some of these wounds, though, with my therapist, so Sam doesn’t get poisoned by all my fear and anger.

This is an astonishing confession for a book that also has Lamott tending to Sam’s colic, describing the wonders of Sam’s first sounds and movement, and basking in the joys of a human soul emerging in rapid increments. Motherhood has long been compared to war, to the point where vital discussions about work-family balance have inspired their own “mommy wars.” Operating Instructions features allusions to heroes, Nagasaki, Vietnam, and other language typically muttered by priapic military historians. Yet Lamott’s take also reveals a feeling that has become somewhat dangerous to express in an era of mansplaining, Lulu hashtags, and vapid declarations of “the end of men.” Men are indeed embarrassing, but are they an ineluctable part of motherhood? It is interesting that Lamott broaches this question long after Sam’s father has become a forgettable presence in the book. And yet months later, Lamott is more grateful for the inherited attributes of the “better donor” in “the police lineup of my ex-boyfriends”:

He’s definitely got his daddy’s thick, straight hair, and, God, am I grateful for that. It means he won’t have to deal with hat hair as he goes through life.

Throughout all this, Lamott continues to take in Sam. He is at first “just a baby,” some human vehicle that has just left the garage of Lamott’s belly:

The doctor looked at the baby’s heartbeat on the monitor and said dully, “The baby’s flat,” and I immediately assumed it meant he was dead or at least retarded from lack of oxygen. I don’t think a woman would say anything like that to a mother. “Flat?” I said incredulously. “Flat?” Then he explained that this meant the baby was in a sleep cycle.

But as Sam occupies a larger space in Lamott’s life, there is an innate ecstasy in the way she describes his presence. Sam is “a breathtaking collection of arms and knees,” “unbelievably pretty, with long, thin, Christlike feet,” and “an angel today…all eyes and thick dark hair.” We’re all familiar with the way that new parents gush about their babies, yet Lamott is surprisingly judicious in tightening the pipe valve. Even as she declares the inevitable epithets of frustration (“Go back to sleep, you little shit”) and trivializes Sam (“I thought it would be more like getting a cat”), Sam’s beauty is formidable enough to spill elsewhere, such as this description of a mountain near Bolinas:

So we were driving over the montain, and on our side it was blue and sunny, but as soon as we crested, I could see the thickest blanket of fog I’ve ever seen, so thick it was quilted with the setting sun shining upward from underneath it, and it shimmered with reds and roses, and above were radiant golden peach colors. I am not exaggerating this. I haven’t seen a sky so stunning and bejeweled and shimmering with sunset colors and white lights since the last time I took LSD, ten years ago.

Being a mother may be akin to a heightened narcotic experience, but that doesn’t have to stop you from feeling.

I suggested earlier that Operating Instructions serves as a precursor to the mommyblog, but this doesn’t just extend to the time-stamp. There is something about setting down crisp observations while the baby is napping that inspires an especially talented writer to find imaginative similes, especially in commonplace activities which those who are not mothers willfully ignore or take for granted. Compare Lamott and Dooce‘s Heather Armstrong (perhaps the best-known of the mommy bloggers) as they describe contending with a breast pump:

“You feel plugged into a medieval milking machine that turns your poor little gumdrop nipples into purple slugs with the texture of rhinoceros hide.” — Anne Lamott, 1993

“I end up lying on my back completely awake as my breasts harden like freshly poured cement baking in the afternoon sun.” — Dooce, February 23, 2004

Armstrong has sedulously avoided invoking Lamott’s name in more than a decade of blogging, but, in both cases, we see just enough imagery squirted into the experience for the reader to feel the struggle. Both Lamott and Armstrong have rightly earned a large readership for describing ordinary situations in slightly surreal (and often profane) terms. (Both writers are also marked in ways by religion. Lamott came to Christianity after a wild life that involved alcoholism. Armstrong escaped Mormonism, eluding to a period as an “unemployed drunk” before meeting her husband, who she subsequently divorced.)

Next Up: Ian Hacking’s The Taming of Chance!