The Expendables was the top grossing movie over the weekend, raking in $35 million, and beating out Eat Pray Love‘s $23.7 million. The Other Guys finished at third, with $18 million, followed by Inception at $11.4 million and, somewhat astonishingly, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World at $10.5 million. The results have caused some to scratch their heads, while others have reacted with the fury of an aging FOX News anchor just a few steak dinners short of a myocardial infarction.

Scott Pilgrim‘s box office failure over the weekend has little to do with Jeffrey Wells‘s deranged dichotomy of “the rank-and-file” warring with “the elite geek-dweeb set” — an impractical characterization that one expects from a paranoid schizophrenic looking for a few magic beans that will grow a tin foil vine. But it was evident from some of the film’s early reviews that the old reactionary guard — which included the hysterical Wells and the frumpy David Edelstein — were going to trash the movie for its audacious syntax — namely, the very visual language that allowed Kick-Ass to make nearly $20 million in its opening weekend back in April.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

On the other hand, it’s possible that Cera can’t entirely be blamed for Scott Pilgrim‘s failure. One only needs to look at the moronic marketing quacks who pushed this movie as if they were lame ducks. Not only did the film’s bright red poster do everything possible to occlude Cera’s presence in the movie, but it failed to communicate what the movie was about. The “epic of epic epicness” tagline tells someone in the dark nothing at all about Scott Pilgrim. And you have to wonder how much money some Universal wordsmith was paid to whip up such anti-commercial inanity.

The first big mistake made by Universal — and there were many — was in failing to market this as a quirky date movie that a young couple might agree upon. (Or perhaps not. Abigail Nussbaum has offered a provocative post suggesting that Scott Pilgrim is misogynistic.)

The second big mistake was in opening Scott Pilgrim during a weekend in which the audience division came down to gender lines. If you were a man, you were expected to see The Expendables. If you were a woman, you were expected to see Eat Pray Love. The Expendables Call to Arms trailer, released a good month before the movie, permitted enough time for these demographic lines to become fixed. And Universal, rather catastrophically, failed to create a Scott Pilgrim trailer that used the movie’s humor as a self-deprecatory selling point to avoid both movies. (I should also point out that, despite my numerous requests to attend a New York press screening, Universal publicists failed to respond by telephone or email. This is not something I can say about the people at Lionsgate, who were very quick to respond, extremely friendly and accommodating. Guess which film received a 1,400 word essay here.)

While it’s true that Scott Pilgrim received a big Comic-Con buzz, it’s very clear that this didn’t translate into mass moviegoers paying to see the flick. It’s also clear from both Scott Pilgrim and Kick-Ass‘s respective takes that a more daring comic book movie isn’t going to translate into an Iron Man 2-style box office bonanza, even as audiences have signaled their desire to be challenged by plot-heavy movies like Inception. A risk-taking comic book movie with a $20 million budget can certainly make a healthy profit, but it’s a harder sell at four or five times the budget. This weekend certainly isn’t the end of movies like Scott Pilgrim. Just don’t expect future movies of this type to have large budgets or originate from the studio system in a good long while. Indeed, had Scott Pilgrim not been up against two pandering movies, it might have attracted more of the crowd. But apparently there’s gold to be panned when you use the Internet to pigeonhole prospective moviegoers into predictable demographics.

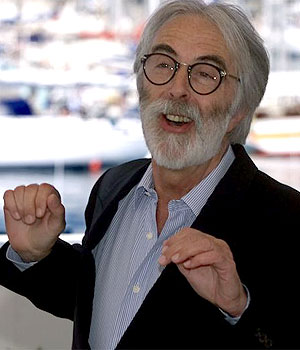

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?