(This is the forty-second entry in The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Moviegoer.)

Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson — a wildly enjoyable and erudite sendup of romantic obsession that is astonishingly peerless and more than a little punk rock in its originality — was included on the Modern Library list, but this Beerbohm stumping was not without modest controversy. Judge William Styron — fulminating in the August 17, 1998 issue of The New Yorker — dismissed Zuleika (as well as The Magnificent Ambersons) as a “toothless pretender.” A novel in which nearly all of the characters commit mass suicide at the end is “toothless”? It does have me wondering if Styron ever dismissed Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief, Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theatre, and Martin Amis’s Money or what he would have made of Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels or Alissa Nutting, Angela Carter, Anne Enright, or Mary Gaitskill at their fiercest. Styron was certainly right about Tarkington, who stands now with the sturdiness of a tray of blueberry muffins baked during the Obama Administration, left for decades on a kitchen island to attract generations of flies and rot into dowdy dust. Of Beerbohm, however, one can only conclude by this ridiculous and unwarranted dismissal that Styron was having a drunken or depressive episode.

Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson — a wildly enjoyable and erudite sendup of romantic obsession that is astonishingly peerless and more than a little punk rock in its originality — was included on the Modern Library list, but this Beerbohm stumping was not without modest controversy. Judge William Styron — fulminating in the August 17, 1998 issue of The New Yorker — dismissed Zuleika (as well as The Magnificent Ambersons) as a “toothless pretender.” A novel in which nearly all of the characters commit mass suicide at the end is “toothless”? It does have me wondering if Styron ever dismissed Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief, Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theatre, and Martin Amis’s Money or what he would have made of Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels or Alissa Nutting, Angela Carter, Anne Enright, or Mary Gaitskill at their fiercest. Styron was certainly right about Tarkington, who stands now with the sturdiness of a tray of blueberry muffins baked during the Obama Administration, left for decades on a kitchen island to attract generations of flies and rot into dowdy dust. Of Beerbohm, however, one can only conclude by this ridiculous and unwarranted dismissal that Styron was having a drunken or depressive episode.

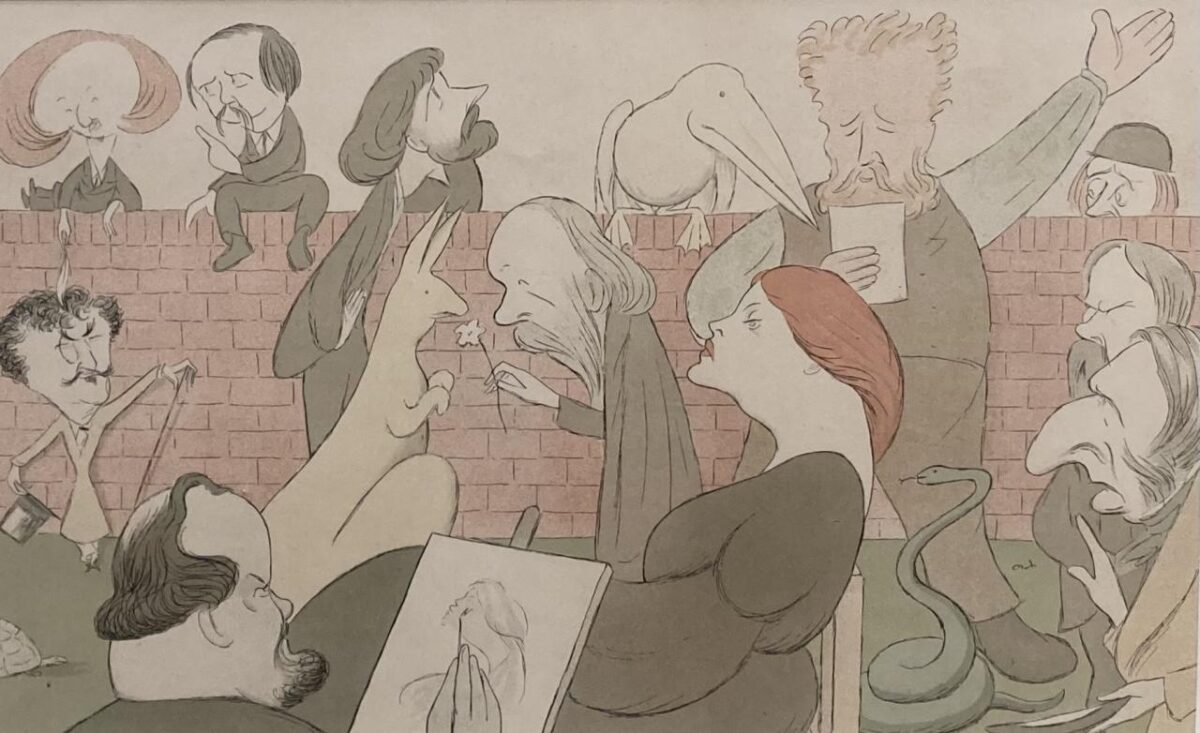

As Beerbohm biographer N. John Hall has pointed out, this mustached satirist — who was friendly with Oscar Wilde, Henry James, and Edmund Gosse — was brilliant enough to attract the attention of William Empson in Seven Types of Ambiguity. Empson singled out this passage:

Zuleika was not strictly beautiful. Her eyes were a trifle large, and their lashes longer than they need have been. An anarchy of small curls was her chevelure, a dark upland of misrule, every hair asserting its rights over a not discreditable brow. For the rest, her features were not at all original. They seemed to have been derived rather from a gallimaufry of familiar models. From Madame la Marquise de Saint-Ouen came the shapely tilt of the nose. The mouth was a mere replica of Cupid’s bow, lacquered scarlet and strung with the littlest pearls. No apple-tree, no wall of peaches, had not been robbed, nor any Tyrian rose-garden, for the glory of Miss Dobson’s cheeks. Her neck was imitation-marble. Her hands and feet were of very mean proportions. She had no waist to speak of.

Of the “trifle,” Empson commended the ambiguity of not knowing whether to be charmed or appalled by the detail. Of the “No apple-tree” and “no wall of peaches” (and even, I append to Empson’s consideration, Beerbohm’s “not discreditable bow”), he praised Beerbohm’s negatives for casting doubt upon the lush imagery. Of “imitation-marble,” he rightfully asked whether Zuleika’s neck was imitating marble or imitating imitation marble. And he likewise called Zuleika’s professed beauty into question, pondering whether it was unique or conventional. Zuleika’s comely qualities are certainly impressionable enough to drive numerous Oxford students mad, leading many to commit suicide. Empson concludes his analysis by writing, “I hope I need not apologize, after this example, for including Mr. Beerbohm among the poets.”

Empson is recused. There are layers within layers here. And Zuleika Dobson is the rare satirical novel of this type that beckons you to read it again, if only to sort the real from the zany. Beeerbohm was a poet of the dandy comic strain — in addition to being a meticulously devilish satirist (“The Mote in the Middle Distance” is unsurpassed as the definitive sendup of Henry James’s hideously bloviated late career style), a formidable caricaturist, and an unexpected radio star in his later years. The language itself, with its recondite words (“chevelure” and “gallimufry”) and its potent phrases guaranteeing rich dopamine hits to anyone with true literary taste (“a dark upland of misrule,” “an anarchy of small curls”), surely reaches the heights of poetry. T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden were just two prominent poets who sang bountiful praises to this “prince of minor writers.”

Even so, Max Beerbohm’s legacy in 2025 is quite possibly in shakier eminence than the underappreciated and veritable genius Henry Green. If Green was a “writer’s writer’s writer,” then surely Beerbohm is a “writer’s writer’s writer’s writer,” enjoyed only by those of us who still schlep dogeared paperbacks of John Barth and Robert Coover and who revere perverse and playful postmodernism even as we feel the hairs bristle on the backs of our necks as some doltish Goodreads sniper targets anyone with bold and subversive taste within their hopelessly unadventurous crosshairs. Even so, Beerbohm is still nestled enough in the canon to have inspired a high schooler to opine last month that she found the narration shift near the novel’s end to be “excitingly strange.” Let us not forget that great literature, even works published more than a century ago, can often be potent enough to stir vital and newfound passion within the young. And in our presently bleak epoch, we need all the good faith exuberance we can get.

That sudden transition to first-person after so many close third-person passages is indeed a thrill. I would likewise contend that the men who get so worked up over Zuleika — to the point of coveting a desire to unalive themselves over her — are still reflected today within the mythical “male loneliness epidemic” served up by wildly obnoxious MAGA incel types as the casus belli for their failure to find any woman who will endure their incessant mansplaining and their monstrous entitlement. Zuleika is rightfully bored by these hopped up doofuses and Beerbohm serves up some dependable zingers over how graphene-thin their souls are (intriguingly, the emphatic allcaps is in the original):

And oh, the tea with them! What have YOU been doing all the afternoon? Oh John, after THEM, I could almost love you again. Why can’t one fall in love with a man’s clothes? To think that all those splendid things you have on are going to be spoilt–all for me. Nominally for me, that is.

And unlike prolix and condescending nitwits like Arnold Bennett (his reputation rightfully destroyed by Virginia Woolf, with only imperious Tory scumbags like Philip Hensher eager to embrace this ancient sexist fiction better used for lining the bottoms of birdcages), Beerbohm is also surprisingly forward-thinking in 1911 when it comes to Zuleika seeing no difference between older men and youth who “fatuously prostrate to her,” inuring her of any deference she could possibly feel for them. At the end of the day, Zuleika, like so many of us, just wants someone to love. And when she does go gaga over the Duke, Beerbohm describes her soul “as a flower in its opetide.” Yet this is a “love” rooted on the Duke’s physical appearance. She is more transfixed by the “glint cast by the candles upon his shirt-front.” And Beerbohm doesn’t stop there. He compare the two pearl buttons on the Duke’s shirt to “two moons: cold, remote, radiant.”

It’s tempting to rope in Zuleika Dobson with Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity. While the two novels are entirely different in tone and sprang from the two writers observing wildly contrasting social milieus, they are both strangely mesmerizing about that one singular feeling that hasn’t yet been hammered out of the human race, even as our dating app age appears primed to reach a natural close: the mad claptrap rush of superficial attraction followed by an obligation to care for an increasingly wilting flower perceived to have lost its bloom. If anything, the 21st century has revealed that all of the social media layers intended for “connection” only buttress the primal superficiality that lurks beneath us all when it comes to matters of the heart and loins. It is the failure to consider some lover or this week’s main character as a palpable human being. True love — predicated on a physical, emotional, and intellectual connection of substance and depth — cannot hope to push past the solipsistic D.H. Lawrence nonsense that remains in place among many Feeld and Fetlife users today. Zuleika Dobson reminds us of the vital need for coruscating wordsmiths to send up this selfish stupidity from time to time, if only to preserve some hope for those who remain committed to the attenuating possibilities of real and enduring romance and the fulsome belonging that naturally emerges from it.

Next Up: Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence!

Both men had turned to screenwriting to stay afloat during the Great Depression. Both men had much to say about the traps and illusions of American life. But it would take longer for West to be reassessed and appreciated — in large part because he was arguably fiercer than Fitz with his fiction. He had his finger firmly on the troubling pulse of feral American life and he wasn’t afraid to use it with the other nine at his typewriter. In a short essay called “Some Notes on Violence,” West pointed to the idiomatic violence that had permeated every corner of printed media: “We did not start with the ideas of printing tales of violence. We now believe that we would be doing violence by suppressing them.” His razor-sharp satire featured philandering dwarves, skewered the hideous contradictions of gaudy Hollywood spectacle, and, in just one of many enthralling flashes of his grimly hilarious invention, depicted a dead horse serving as au courant decor at the bottom of a swimming pool. (In an age in which urine-drinking is prescribed as a COVID remedy and reality star Stephanie Matto makes $200,000 selling her farts in a jar, one wonders why the present fictional landscape doesn’t reflect our scabrous realities and why 85% of today’s gatekeepers are so hostile to such a necessary dialogue between fiction and life. But then this is the same universe in which Hanya Yanagihara’s excellent, quite readable, and wildly ambitious new novel, To Paradise,

Both men had turned to screenwriting to stay afloat during the Great Depression. Both men had much to say about the traps and illusions of American life. But it would take longer for West to be reassessed and appreciated — in large part because he was arguably fiercer than Fitz with his fiction. He had his finger firmly on the troubling pulse of feral American life and he wasn’t afraid to use it with the other nine at his typewriter. In a short essay called “Some Notes on Violence,” West pointed to the idiomatic violence that had permeated every corner of printed media: “We did not start with the ideas of printing tales of violence. We now believe that we would be doing violence by suppressing them.” His razor-sharp satire featured philandering dwarves, skewered the hideous contradictions of gaudy Hollywood spectacle, and, in just one of many enthralling flashes of his grimly hilarious invention, depicted a dead horse serving as au courant decor at the bottom of a swimming pool. (In an age in which urine-drinking is prescribed as a COVID remedy and reality star Stephanie Matto makes $200,000 selling her farts in a jar, one wonders why the present fictional landscape doesn’t reflect our scabrous realities and why 85% of today’s gatekeepers are so hostile to such a necessary dialogue between fiction and life. But then this is the same universe in which Hanya Yanagihara’s excellent, quite readable, and wildly ambitious new novel, To Paradise,