B & ME: A TRUE STORY OF LITERARY AROUSAL

by J.C. Hallman

Simon & Schuster, 288 pages

I first heard of Nicholson Baker not long after I was released from the hallowed corral of higher education. I was in San Francisco at the time, living out the third of my thirteen adventurous years there and working for a slightly sinister attorney. I had learned from the newspapers and the alt-weeklies that a bearded man with a soft sussurating voice had a rustling sword to wield against the dazzling main library that had just replaced the original damaged by the Loma Prieta earthquake. The crackling glitz of digital catalogs and sleek architecture designed by the same man who gave us the Jacob Javits Convention Center’s echolalic headaches had arrived with a soul-crushing toll. The San Francisco Public Library was in the process of discarding its books, claiming that there wasn’t enough space in this new commodious sanctum for the whole collection. Moreover, the library was tossing out its analog card catalog, viewing it with the same disdain as last week’s banana peels and the previous weekend’s sticky tsunami of used condoms. In an age before Wikipedia and e-books, this was sacrilegious to anyone who cared about knowledge.

Baker became something of a one man force against these disheartening developments. He sued the library. He conducted a clandestine expedition with a few pals to sneak into the old library, where he measured the catalog’s dimensions to debunk the library officials’s claims. It became clear that Baker was a preservationist and an eccentric rabble-rouser, perhaps the literary world’s answer to Ray Davies. It is safe to say that I was smitten by these gestures. Baker was precisely the kind of writer I needed to read. I had no idea at the time that his work would eventually mean a great deal to me.

I started with Vox, Baker’s 1992 phone sex novel, which I knew that Monica Lewinsky had purchased as a gift for Bill Clinton. At the very least, I counted on tawdry titillation. These were, after all, the days when streaming porn involved a badly pixelated two minute video clip crawling through a creaky phone line at 56K, freezing into a blur at some inopportune moment. It was a very embarrassing epoch for pre-Tinder pioneers hoping to ride the edge of a new frontier. What I discovered in Vox was a surprisingly thoughtful study of loneliness, with two people circling around their lustful feelings to reveal the full panorama of their intimacies. The big clue was the way Vox‘s Jim referred to the male member as his “bobolink,” his “sperm-dowel,” and his “Werner Heisenberg.” That Jim could not bring himself to say “cock” or “dick” or even Eric Idle’s “one-eyed trouser snake” was a noble revelation on how those who are insatiably curious cannot always find solace in the explicit. And this was a fascinating predicament: how could educated, articulate people with randy instincts express themselves when the modal vernacular left little to the imagination? Sex wasn’t something that could just be ignored. Were there others out there who faced the same predicament?

I continued on with The Fermata, which involved a man named Arno imbued with the power to stop time through quite specific analog elements: by the snap of his fingers or by spooling an elaborate thread around a washing machine. Arno, who is incapable of writing his autobiography, stops time to see women naked and, in what was considered a notorious literary moment in 1994, to masturbate on a woman’s eyelashes. But like Vox, these sexual fantasies actualized in print concealed larger longings to feel and connect. What was so interesting about this novel was the way in which words like “heart” had been almost totally plucked for the sexual realm (“clit-heart beats,” “heart-shaped ass-curve,” “peep to his heart’s content”), leaving little room for the earnest and dowdy ways in which these words had been used before. (Even Arno becomes dissatisfied with the word “erotica,” substituting “rot” in its place.) Baker, who would later write a very long and fascinating essay about the historical usage of “lumber” in prose and poetry, was clearly someone who cared deeply about language and the way that gushing souls were drawn together through it. Yet he seemed to be making a larger point about how unbridled fantasies contributed to limitation, almost as if embarrassment had to flee somewhere well beyond the vanilla. (2011’s House of Holes — a comparatively late entry in what can be snugly dubbed Baker’s “sex trilogy” — would subvert this idea altogether, coming close to Samuel R. Delany’s notions of pornotopia with its tree copulation, groan rooms, sapient creatures assembled from naughty bits, and horny dismembered arms.)

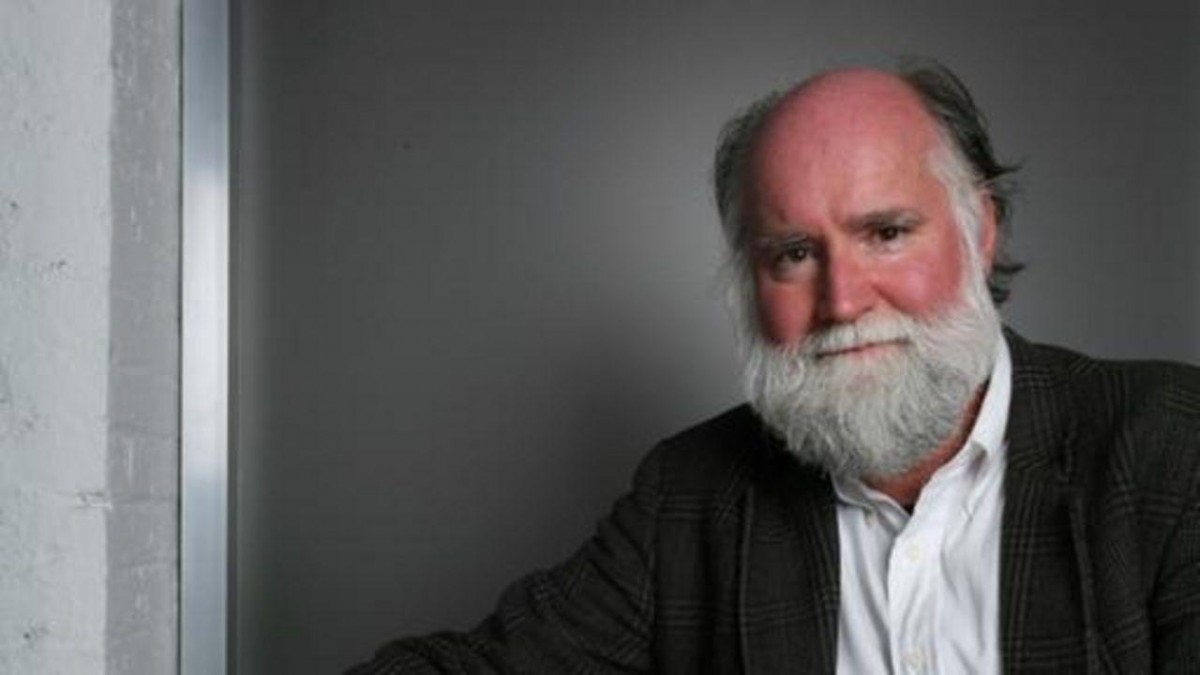

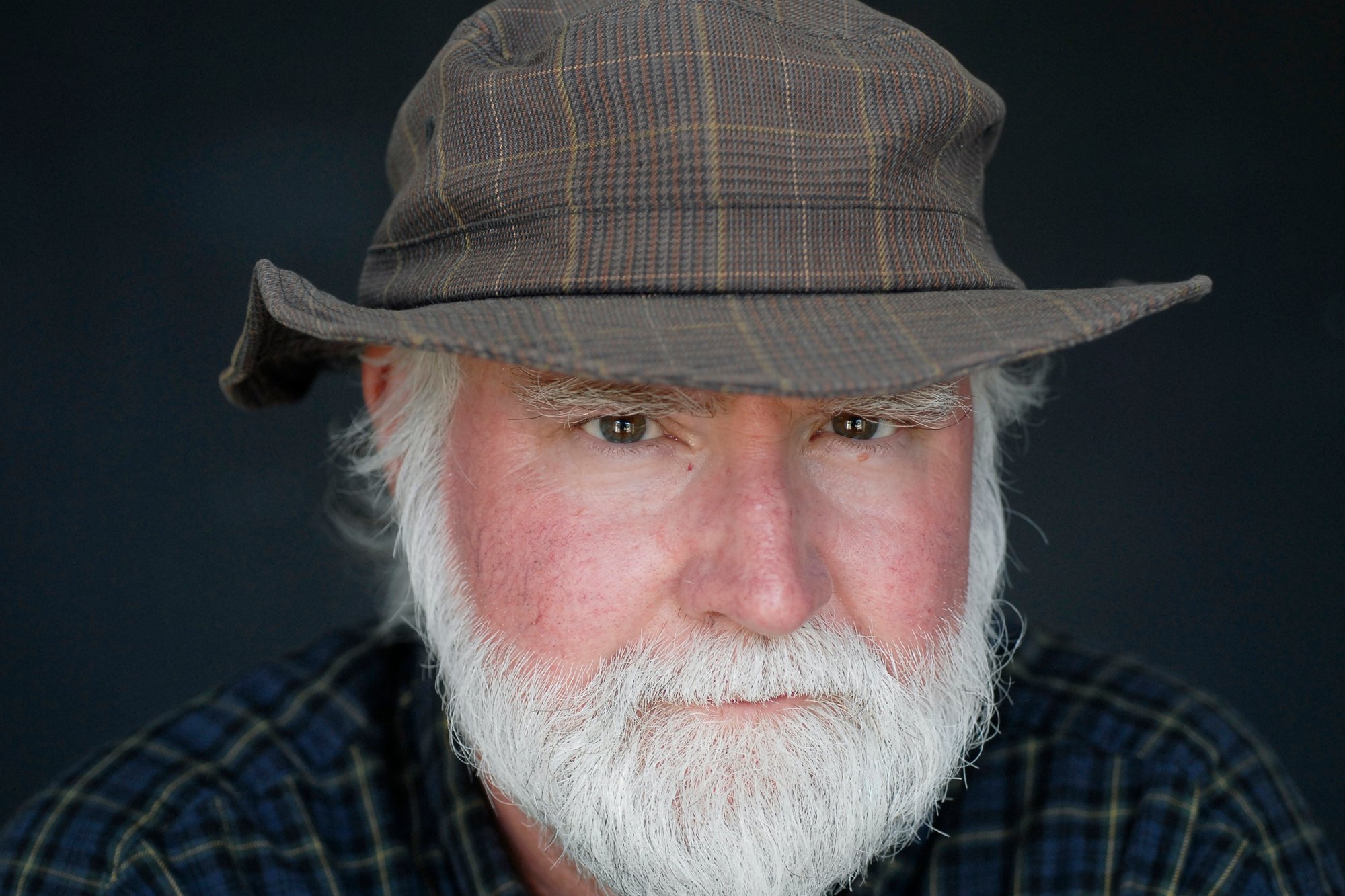

And then there were the other Baker novels, such as The Mezzanine, Room Temperature, and A Box of Matches, that offered rich and beautiful tapestries composed from the pedestrian. In The Mezzanine, Baker had performed the seemingly impossible feat of liberating our daily world from Madison Avenue with his elegant and joyful descriptions of bathroom stalls, the sensation of plastic bags, and vacuums making “swaths of dustless tufting lean in directions that alternately absorbed and reflected the light.” Yet for all his precision in depicting quotidian consciousness, he was highly inexact in recalling Updike’s prose from memory in U & I, a zany and uncategorizable book somewhere between personal essay and cultural writing about Baker’s mania for John Updike. Any Baker fan was forced to wonder what united these various obsessions, but there was always a benign quality to Baker’s prose that made some of his seemingly creepy pastimes feel quite harmless and, indeed, a bit liberating. (It is worth observing that Baker himself is an exceedingly kind man: one who was even gracious enough to participate in a roundtable discussion of his controversial book, Human Smoke, that appeared on these pages in 2008.)

Perhaps this was what books were meant to do. It is one thing to read a good yarn, but it is quite another to find a volume that demands that readers feel more passionately about the world around us, simply by dint of robust observation kindled by literary bellows. Joyce, Woolf, Murakami, and Susan Minot’s Rapture have all gone to this place, stretching out minutes of life over dozens of pages, and often lacing their tender contributions with the libidinous. But maybe the connection to sex suggested that palpable obsession in any form was ineluctably arousing.

Perhaps it was inevitable that someone would do for Baker what Baker did for Updike. In B & Me: A True Story of Literary Arousal, J.C. Hallman has contended with Baker’s work in a highly personal and endearingly alarming way, pulling out his flopping Richard with flair and humor. The book includes detailed investigation of Baker’s author photos, a two column chart comparing Room Temperature‘s Mike with Baker that runs just under three pages, and an axe to grind against Martin Amis (who once griped to Baker that he had used “strum” — featured in Vox — as shorthand for masturbation in London Fields, even though there is no mention of “strum” at all in Amis’s novel*). Hallman is decidedly more confessional and more recklessly zealous than Baker. We’re not even twenty pages into the book when Hallman reveals that, as a teacher, he feels “[t]here are women in your classes that you can’t actually wait to get and home and masturbate to.” He is also quite libertine in the way he describes his girlfriend Catherine’s orgasms. But behind all these unapologetic lunges for the curtain separating a febrile and almost pornographic relationship to books from a common reading experience is a free association that, with its grab bag embrace of the Brothers James and James Agee’s A Death in the Family, offers a compelling prima facie argument for offbeat autobiographical criticism. Or as Hallman puts it, after quoting David Simpson’s “Speaking Personally” — a huffy response to Jane Tompkins’s “Me and My Shadow”:

In other words, what one should do is ignore reality so as to understand the self that exists in reality, the self that must be theorized about. A general lack of enthusiasm for excretory activity perhaps explains why traditional critics often wind up just so full of shit.

Tompkins was rightly criticizing the literary world’s failure to allow for a certain strain of highly personal criticism, of being “squeezed into a straitjacket” where words like “epistemology” and “hermeneutics” are crammed into a dull academic stock made for an increasingly flavorless soup. But is it possible that the self is the new critical triangulator? That writing about books in a provocatively personal way, in which arousal is very much part of the expressive process, might yield new forms of excitement and interpretation?

Hallman’s book has been received coldly by a few critics, who have become a bit obsessed with money shot imagery in their vituperative assessments. Perhaps it is because Hallman is either brave or foolhardy enough to articulate his ardor on a level rivaling a Vivid Entertainment production:

Metaphorically speaking, I want Nicholson Baker to come on my face, and to keep coming on my face, again and again — and isn’t that all any reader should want, isn’t that the explicit lodged way deep down in the implicit? Wouldn’t that — same-sex trust and acceptance, particularly among aggressive-prone men — amount to the beginning of a better civilization? I want Nicholson Baker to ejaculate all over my face, and I don’t care if it’s about power, and I don’t care if I’m left puffing and spluttering to keep it out of my mouth. I want Nicholson Baker to keep spewing all over my face until I can’t possibly take it anymore.

I certainly never felt this way reading Baker, although I am pretty sure that I possess reading kinks that are far more disturbing than J.C. Hallman’s. The fierceness of this confession shouldn’t discount the other vital part of hooking up with an author through reading. For much as Vox and The Fermata established that intimacy is based on more than one’s cork popping in a froth of joyful juices and buoyant shouts, literary arousal also includes the conversations you have while lying naked in bed before, during, or after being aroused.

There is one point in B & Me when Hallman has some distressing idea, one conveyed solely through gossip, that Baker had written a book denying the Holocaust. But Human Smoke‘s true purpose is to boldly suggest that pacifist actions might have contributed to stopping the loss of lives or preventing war. This makes Hallman’s relationship with Baker akin to that of someone asking a lover’s previous sexual partners if there are any irksome personality qualities or troublesome STDs that he should know about.

And perhaps this is why Hallman himself must disclose his own sexual history with Catherine or the story behind the “hunchback” cyst on his back. If he wishes to consummate meaningful literary arousal, then this airing of personal laundry is an inescapable part of the package. He uses loaded words like “interchangeable” and “tool” and even invites Baker to a bed and breakfast, but, while Hallman is keen to tell all to the reader, he is not so willing to investigate his own gushing complicity in the literary partnering, even as he sees his real life partner Catherine start to tire of his Baker relationship. Hallman’s feelings for Martin Amis are perfectly understandable: that of a man condemning his lover’s ex-boyfriend. But intense literary arousal — as I have learned during the last two years I have studied Joyce — often involves an exclusive relationship leaving little room for being polyamorous. Shouldn’t literary arousal be open enough to allow for sleeping around? Reading, as it turns out, is just as complicated as hooking up in real life. That doesn’t make it any less thrilling and, under the right circumstances, pleasantly scandalous. The one thing I’ll always know is that anyone who has Nicholson Baker as a notch on their belt is likely to be good in the sack.

* — A Google Books search, an Amazon “Search Inside the Book” query, and a plain text file search confirms that Amis never used “strum” in London Fields, which Hallman also reports in his book. Indeed, there is an inexplicable hostility towards Baker among writers in Amis’s immediate circle of friends. In Will Self’s mediocre novel, Walking to Hollywood, Baker is needlessly dissed: “…and I thought of Baker himself, with whom, a decade before, I had shared a stage at a similar book festival in Brighton. I remembered how pinheaded he seemed — considering the size of his thoughts….” Christopher Hitchens also wrote a damning review of Human Smoke in the New Statesman, calling Baker “self-satisfied” and stating that he “grew increasingly impatient with Baker’s assumption of his own daring transgressiveness.” These are curiously personal slams, perhaps a mystery that will remain as unanswered as the motivations behind Baker’s brief move to the UK. But if reading is a plausible form of arousal, the phrase “lie back and think of England,” suggesting an unadventurous torpor related to national identity, may also account for the hostility.**

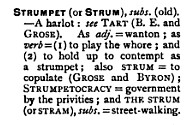

** — In an effort to settle the “strum” controversy, Evan Schaeffer (and a few others by email) have pointed to Calum Marsh’s review in The New Republic, in which Marsh observed that “strumming” appeared in a similar context within Money: “Hello again. Well, here we all are, lying flat on our backs and strumming ourselves like bent Picasso guitars.” Mr. Marsh is correct, but Martin Amis is not the first person to use “strumming” as a sexual euphemism. According to Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang, “strumming” was first used in a sexual context in the 19th century:

Additionally, “strum” was recorded in copulative usage in William Ernest Henley’s Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present, Volume 7 (published in 1904, some eighty years before Amis’s Money):

The phrase “strum the banjo” has long been in slang use, although the etymological texts I consulted don’t have a precise date of origin for its first use as a masturbation euphemism. While it is doubtful that Amis was the first to use “strum” in this solipsistic context, it is indeed quite odd that he would declare first coinage, much less condemn Baker for his usage (especially when Baker included many other sexual euphemisms in Vox).

I reached out to Nicholson Baker for comment. Baker replied, “I admire Martin Amis, and if there’s anyone in the literary bowlerama I’d like to have used the word ‘strum’ before I did, it would be him.”