Laurie Sandell recently appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #306.

Laurie Sandell is the author of The Impostor’s Daughter.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering if the coalminer was an impostor.

Author: Laurie Sandell

Subjects Discussed: Chicken recipes, the quest for truth within memoir, how narrative shapes and stretches truth, subjective vs. objective accounts, the essay written anonymously for Esquire, memory vs. concrete evidence, emails from Ashley Judd, how hard evidence enhances a visual diagram, lawyers sifting through evidence, the use of clothing against background, working with a colorist, becoming one’s parents, the use of motion lines, adopting comic book semiotics, drawing from an intuitive part of the brain, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, feeling liberated in comic form vs. restrictions in textual form, maintaining privacy vs. spilling all details to the public, diagramming environment, knowing the lay of the land, static panels, consulting graphic novels, Scott McCloud, arrows pointing to figures, strange stays in five-star hotels, sketching out the book before drawing, taking the story arc from the text version of The Impostor’s Daughter, structure and spontaneity, maintaining momentum vs. contending with painful memories, emotional change and artistic change, whether or not writing is the proper way to exorcise demons, the story of Sandell’s father as a former sense of identity, the ethical dilemmas of narrative seduction, and fearlessness.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Sandell: Yes, it is.

Correspondent: It’s been said that memory is the greatest liar of them all. It’s been said — by, I believe Lincoln — that you have to have a great memory to be a great liar.

Sandell: Right.

Correspondent: So given this conundrum, I’m wondering to what degree you relied on your own memory and to what degree you relied on reference shots. You have, for example, illustrations that crop up within the course of the book. This leads me to wonder about other specific details. But maybe we can start on memory vs. concrete evidence.

Sandell: Well, you know, it was a mix of memory and concrete evidence. On the one hand, I had a lot of concrete evidence because I had interviewed my father over a period of two years and I tape recorded our conversations with his knowledge. This was leading up to the Esquire piece when I had a 300-page transcript. So most of the things that my father said in the book came directly from those transcripts. So he’s telling stories from his past. Those came directly from my father’s mouth.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Sandell: As far as — I’m trying to think. I don’t know. What else?

Correspondent: Well, I could actually cite specific examples.

Sandell: Okay, sure.

Correspondent: For example, the difference between the narration and what is actually spoken in the text bubbles.

Sandell: Right.

Correspondent: Here’s one example. When you’re working at the office, you have a text box point to the screen: “Have you considered inpatient treatment.” We don’t actually see the email on the screen.

Sandell: Okay.

Correspondent: We actually see your particular perspective.

Sandell: Right.

Correspondent: And so I want to ask you about why that particular emphasis — I mean, that’s inherently subjective. We’re counting on your subjective viewpoint as to what is on the screen. As opposed to later on, when we actually see what’s on your screen, when you’re on your laptop in your motel room.

Sandell: I need to be honest. The reason you didn’t see that screen was probably because it didn’t fit in that box.

Correspondent: Okay.

Sandell: And so I had to deal with little callouts so you could actually see what was on the screen. But the interesting thing about the process of putting together all this evidence — a lot of it really was evidence — is that there were so many emails. For example, that email was an email, I believe, from Ashley Judd.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Sandell: And I have those emails from Ashley Judd. I have the emails from my father. You know, I worked with a private investigator for two years. So I have all of his information and the lawsuits he compiled and all the various evidence and things written by my father. You know, I think — did you ever read Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy?

Correspondent: No, I never read that.

Sandell: It’s a beautiful memoir. Ann Patchett later went on to write Truth & Beauty: A Friendship.

Correspondent: That’s right.

Sandell: And one of the things that Ann Patchett said in her afterword — after Lucy died, Ann Patchett wrote an afterword to the book — and she described how, at a reading, someone said to Lucy Grealy, “How did you remember all those details about your past?” And she said, “I didn’t remember it. I wrote it.” And people were a little bit up in arms about that. But she was pointing out the fact that this was a piece of art, it’s a piece of subjective memory, and the most important thing is to show the emotional truth of the situation. And I would say that in my case, because I have so much evidence, and evidence that Little Brown asked to say and anytime I’ve done television, they’ve actually asked to see the evidence, I feel pretty comfortable that there’s not going to be any big explosive James Frey situation.

Correspondent: Well, to what degree were they asking for the evidence? Because we’re talking about transcripts. We’re talking about investigative reporting. This is all text right now. And here you are. You have a visual document here.

Sandell: Yes.

Correspondent: You have to construct something from the text here. So it’s a wonder that evidence even means anything if it’s a visual result.

Sandell: I think it does. I mean, the visual result is obviously my memory. It’s the way I remember the situation.

(Image: Brantastic)

BSS #306: Laurie Sandell (Download MP3)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

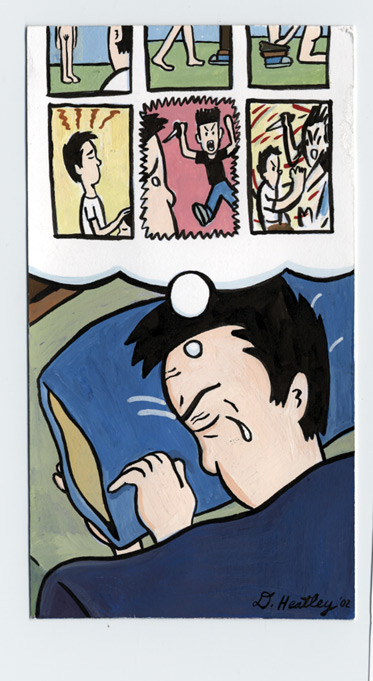

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.”

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.” The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories.

The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories. Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,

Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,