When you feel the earnest desire to kill yourself — as I did for about five minutes during the evening of June 26, 2014 — you truly believe that, no matter how kind and sharp and talented you are, there just isn’t a place for you on this planet. That none of the solicitude or the careful work or the unique qualities you offer the world can ever atone for the concatenation of persuasively exaggerated sins buttressed by a dark and singular and unforgiving demon who wants to pull you down, one smashing away at the beatific inner town that you’ve spent decades carefully constructing.

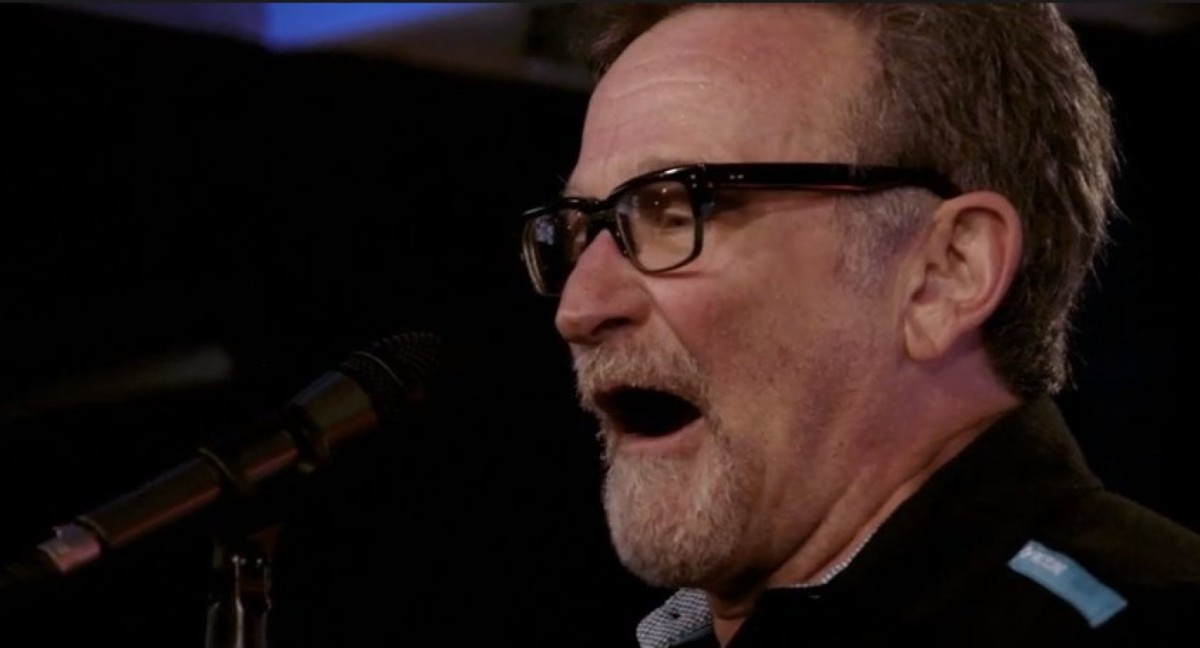

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was trying to sell off his Napa Valley estate, that he had suffered an unsuccessful return to television (The Crazy Ones was canceled after only one season), and that, sometime in July, when he was trying to seek help for his pain in Minnesota, a picture of Williams at Dairy Queen made the rounds on on the Internet. He’s standing with his hands crossed, the obliging professional trying so hard to sustain a dutiful grimace when there were bigger stakes. All Williams wanted was an ice cream cone, one small step back into the hearts of those he entertained for decades.

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was trying to sell off his Napa Valley estate, that he had suffered an unsuccessful return to television (The Crazy Ones was canceled after only one season), and that, sometime in July, when he was trying to seek help for his pain in Minnesota, a picture of Williams at Dairy Queen made the rounds on on the Internet. He’s standing with his hands crossed, the obliging professional trying so hard to sustain a dutiful grimace when there were bigger stakes. All Williams wanted was an ice cream cone, one small step back into the hearts of those he entertained for decades.

There’s a moment at the end of World’s Greatest Dad, a highly underrated film by Bobcat Goldthwait containing one of Williams’s last great performances, in which Williams played an aspiring writer named Lance Clayton who covers up the embarrassing death of his son Kyle. Nobody cares about Kyle’s suicide until his note, penned by his father, is discovered and published in the school newspaper. Lance pushes the lie further by writing a phony journal, which attracts the attention of the prospective publishers that he had been coveting for years. It’s the devilish fatalism that happens far too often in America: the fifteen minute fluke propped up instead of someone who works eighty hour weeks and pays his dues, the middle-aged man pushed aside for the young life unlived, an act of unpardonable deceit promulgated for a notch up the ladder after years of honest labor.

In the film’s final scene, Lance confesses the truth to the school, saying via voiceover, “I used to think the worst thing in life was to end up all alone. It’s not. The worst thing in life is ending up with people who make you feel all alone.” What makes Goldthwait’s film and Williams’s performance so meaningful is how this declaration forces the audience to sympathize with the disgraced outcast nobody wants to deal with. Philip Seymour Hoffman, another formidable talent who killed himself, was also good at playing these pariahs, whether Allen in Happiness or Truman Capote. There are also resonances with David Foster Wallace, who also killed himself. One is reminded of the story, “The Depressed Person,” in which Wallace’s titular character sees her group of supportive friends vanish as the depression continues to corrode her core. There was something essential that these three mighty artists hid behind their humor, the understanding that America’s alleged desire for misfits inevitably collides against a hard and self-protective barrier. That all three suicides are as cruelly permanent as the emotional impact of their best work says something, I think, about what we now demand of artists and people in America.

Suicide doesn’t allow for heroes. Nor do the less tragic cousins: the attempt or the ideation. The person wishing to help, even when she likes the person, can often feel a begrudging duty or guilt that she does not care enough. The person who comes close to killing himself, which is a feeling not unlike being swallowed by a buckling whale with other concerns on his mind diving without mercy into a chilly deep sea, accumulates endless emotional debt that he can never repay, even as he seeks help and works very hard to stay positive and understand his illness, often with the callous stigma that he is permanently damaged. All parties come to know these terrible contradictions.

But the only truly common bond that all parties can have is compassion.

There has been a goodhearted clarion of calls on Twitter after Williams’s suicide, entreaties to anyone on the edge to call a hotline and know that they are loved. But suicide and depression aren’t nearly so pat, especially in a hungry and vituperative digital world that awaits some flawed figure to expose some chink in the armor (an appearance at Dairy Queen or, in my case, two deleted tweets reflecting a great deal of pain that I have spent much of the past six weeks sobbing out of me).

Williams will have the comedy. He will always be remembered for seizing the day, whether in the only Saul Bellow film adaptation ever made or as John Keating in Dead Poets Society. But I’ll remember him for the indelible, self-loathing characters he played so well in Cadillac Man, Death to Smoochy, One Hour Photo, and World’s Greatest Dad. There was a dark and tormented man inside those performances that wanted to reveal the contradictions of our nation and that demanded a grander compassion, one more vital to our humanity than shouting some feel-good catchphrase while standing at the top of a desk.