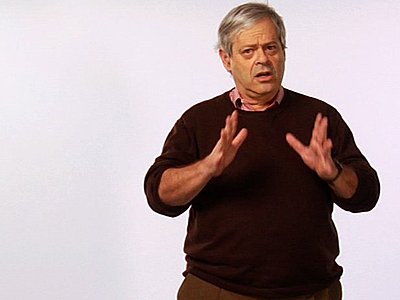

Simon Winchester is most recently the author of The Men Who United the States. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #87.

Author: Simon Winchester

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Becoming an American citizen, the diamond hoax of 1872, revisiting historical locations in contemporary times, driving over Donner Pass during a relentless blizzard, Clarence King, buying a tract of land in Montana, having Huey Lewis as a neighbor, attempts to buy chains from mysterious opportunists, avoiding the term “flyover states,” American Heartbeat, William Gilpin’s claim that the Western Territory of the United States could accommodate two billion people, New Harmony, David Dale Owen, Robert Owen, belief scams, the Hudson-Mohawk Gap, the construction of the Erie Canal, geopolitics, efforts to get at the truth about the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, 99% Invisible, standing up for the forgotten Ellis Chesbrough, The Jungle, leaving out historical figures, surveying and mapping the territory as essential elements of mapping the states, the Warren Map of 1858 as the definitive map of the United States, Roosevelt slicing a map of the States with a crayon to project his image of the U.S. interstate highway system, how American policy makers wavered from the norm, the “Yellow Book” basis for the interstate system, the military connections within the origins of America’s roads, Eisenhower as geographical observer, the UK Ordnance Survey vs. the U.S. Geographical Survey maps, rural electrification, Robert Caro’s LBJ volumes, “the pitiless arithmetic of capitalism” and its influence on areas of the States that didn’t get electricity, Samuel Insull, the real model for Citizen Kane, Roosevelt’s New Deal policies for the farmers, Western Ohio political ironies, Sacagawea, challenging Winchester on the lack of women in >The Men Who United the States, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the influence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the slavery debate, Ameila Earhart, risky book titles in an age of Jezebel, men and big ideas, Winchester’s crush on Donna Reed, ideas vs. physical links uniting the States, gender equality, John Wesley Powell’s extraordinary climbing claims, arguing over the legacy of Theodore Dehone Judah, the N Judah line and the 38 Geary, Ted Judah vs. The Big Four, Winchester’s six page love letter to NPR, NPR’s transphobia over Chelsea Manning, NPR on Iran, misreporting Gabrielle Giffords’s death, Democracy Now, This American Life, NPR vs. BBC and CBC, >Winchester’s 1981 thoughts on public radio, Bill Siemering and the origins of “All Things Considered,” the dormant exploratory impulse vs. guys who look at computers, metaphorical nation states, Winchester founding a newspaper, innovation vs. repeating the last two centuries of history. and Winchester’s forthcoming book on the Pacific Ocean.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Winchester: It’s lovely to see you again.

Correspondent: I was saying before. Last time we talked, you weren’t an American citizen.

Winchester: I wasn’t. It was in San Francisco.

Correspondent: Yes, it was.

Winchester: As I recall, I was enormously hungry and a little bit bad tempered.

Correspondent: Oh yeah.

Winchester: But this morning I’m very good.

Correspondent: No, no. You’ve been extraordinarily charming. Anyway, one of your strategies for this book involved revisiting many of the locations and taking in the sights as they are today. You encounter military installations on the Lewis and Clark route. When you visited Diamond Peak in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, the site of the Philip Arnold/John Slack diamond hoax of 1872, you express a certain kind of romantic disappointment that there isn’t a diamond for you to pick up and pluck.

Winchester: (laughs)

Correspondent: And there’s also, of course, your journey by car over Donner Pass, kind of getting a sense of what it was — because you were traveling through a blizzard. So my question first and foremost is: What advantages are there in visiting a place today when there is often no trace whatsoever of the original geography? Was this a peculiar criteria that you applied in selecting the locations you decided to write about for this book? What happened here?

Winchester: I don’t think they were criteria. Let’s go through them one by one. I was following the Lewis and Clark trail and they started, as you probably remember, in St. Charles, just north of St. Louis. And you turn left. You turn westwards and go up to the Missouri. And there isn’t a lot that’s very interesting until you come to this funny place called Knob Noster, which has to be one of the more peculiar town names in America. And I remembered when I got there and read Lewis’s account of being there and finding some sort of snake that gobbles like a turkey or a turkey that make noise.

Correspondent: Gobbles knobs.

Winchester: Yes.

Correspondent: We’re getting naughty very quickly. (laughs)

Winchester: Stop this. And I remembered that years before when I wrote an extremely unsuccessful book about the Midwest that I had been to Knob Noster because it’s the size of this enormous Air Force base. So I wanted to go and see how the Air Force base had changed in the thirty, forty years since I’d last been there. And of course, it has changed in a very important and significant way. The diamond field in Wyoming? Well, this all relates to the career of an extraordinary geologist called Clarence King, who happens to be a great hero of mine. The first ever director of the United States Geological Survey. He made his name by uncovering a fraud, the people you mentioned, which cheated a lot of wealthy San Franciscans — a great proportion of their fortune — by claiming to have found a field full of diamonds. They, of course, salted the diamond. They bought them cheaply in London and then put them in anthills. And so I went down to Diamond Peak, which is an extremely lonely place. And I’m walking along and thinking, “Wouldn’t it be nice if I could just uncover a diamond or an emerald or a sapphire?” But, no, there’s nothing left.

Correspondent: Were there any anthills at all?

Winchester: There were lots of anthills. Oh yes.

Correspondent: Because you didn’t mention that in the book.

Winchester: Well, there were.

Correspondent: I mean, come on. You’ve got to be grateful for second place, right?

Winchester: (laughs) Indeed. Quite. But Diamond Peak was there, just as described. But it started to snow. It started to get very cold and very windy and we were a long way from anywhere and it was starting to get dark. So we thought, “Well, there are no diamonds.” So screw it. I’m going home.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Winchester: Sorry if I didn’t mention the anthills.

Correspondent: I was in suspense.

Winchester: I’m sure you were.

Correspondent: You disappointed me on that point.

Winchester: I’m so sorry. I beg your pardon. And then Donner Pass, well, that was some while ago — not on doing specific research for this book. But I bought a tract of land, which I’ve since sold.

Correspondent: Montana.

Winchester: So foolishly. Yes. On Route 93 in Western Montana. And I was hightailing it back to San Francisco because I had to catch a plane back to Hong Kong, where I was living at the time. And so I was going fast on Route 80. West. And all the radio stations were saying that the Donner Pass is dry and clear, to use the expression. But it clearly wasn’t. Because since I started leaving from Reno and going up the hills, it started to rain. There were flashing lights on the side of the road, saying DONNER PASS CHAINS REQUIRED. And then I got up to where the rain turned to sleet, then to snow, then to driving snow. And then there was a Highway Patrol barrier saying ONLY CHAINS REQUIRED. And, of course, inevitably, this being America, there were a couple of entrepreneurial chaps by the side of the road, saying, “Oh! You want chains? We’ll give you chains. We’ll sell you chains.”

Correspondent: No doubt you were Huey Lewis’s mark.

Winchester: Huey Lewis was next in the piece of land in Montana. He was my next door neighbor.

Correspondent: Yeah. I was stunned.

Winchester: Huey Lewis and the News.

Correspondent: I was wondering if he led you astray. Now I have the timeline absolute here.

Winchester: (laughs) No. But what did happen, which I didn’t put in the book, was that I paid my $75. I had the chains put on. I crossed the Donner Pass. It’s fairly dramatic during a horrible snowstorm. But the point of my telling the story is that the Union Pacific trains were roaring through it at the same time with no problem caused by the snow, illustrating that that was indeed the logical place for the Union Pacific route to go. But then I got over the summit finally. About two in the morning. Started going down the other side towards Sacramento. The snow turned to sleet. Turned to rain. I unbolted my chains, put them in the trunk of the car. Note I say “trunk” now, not “boot.” Because I am an American.

Correspondent: Good on you.

Winchester: Thank you. Drove over the Bay Bridge ultimately to the hotel I stay in, which is a very nice hotel. I’ve always stayed because I’m from Hong Kong. The Mandarin Oriental. San Francisco, California. And the chap at the door says, “Oh, hello. Good morning, Mr. Winchester.” He’s been there for so long. “Do you want these chains?” And I said, “No no no. Just put them aside.” So he took the chains out and labeled them. Every time that I have stayed in the Mandarin, in the twenty years or fifteen years since that moment, always on my bed are Mr. Winchester’s chains.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Winchester: As if I get up to something really unspeakable in my room involving chains.

Correspondent: Wow.

Winchester: Indeed.

Correspondent: This has all sorts of implications.

Winchester: (laughs)

Correspondent: This kind of strays from my original question about using the actual physical presence of Simon Winchester at these locations as a way of writing about them. But it seems to me that you are almost atoning for past peregrination mistakes in previous books. Is that safe to say?

Winchester: Well, one particular book.

Correspondent: Okay. Alright.

Winchester: So nice of you to mention it. Yes, thank you.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Winchester: I am perfectly happy to admit it. This book, The Men Who United the States, is my second attempt to write about the United States in book form. The first was in 1976 when I was based in America, in Washington, for The Guardian, and had this, what I now realize to have been, somewhat naive belief that the essence of America, the quiddity if you like of the country, could be found not in the effete East or the decadent West, but in the imperturbable, solid, rock-ribbed heart of the country. The Midwest. So I took six months’s leave.

Correspondent: Thank you for not using the term “flyover states.”

Winchester: I certainly would never dream. I did once actually. So I’ve got to confess that in case.

Correspondent: Okay. Well, you’ve really become a great American.

Winchester: Well…

Correspondent: A very, very noble one. (laughs)

Winchester: And also I happen to like the Midwest. So I didn’t rent a car. I drove my Volvo, I remember, and spent six months driving on I-35, which goes from International Falls, Minnesota, through Minnesota, Iowa, a bit of Missouri, where the Air Force base was, Kansas, Oklahoma, down through Texas, and finally ends in Laredo, up and down and up and down and wrote this book. The timing was for it to come out during the bicentennial year. 1976. And to be fair to the book, which was called American Heartbeat, it was credibly reviewed. I mean, people were very generous. But not the people who buy books. They were not generous at all and when the royalty statement came in ’77, or at least I couldn’t dignify it with the term “royalty,” it showed that it had sold twelve copies. So it was not a success.

Correspondent: Really?

Winchester: It was a dismal, dismal commercial failure.

Correspondent: Wow.

Winchester: So in a way you’re right to use the word “atonement.” This new book is, let us say, learning from the lessons of that failure. The one thing I was determined to do was to write a book that was in no way similar to the book that I’d written in ’76.

Correspondent: Wow. That’s incredible. Well, I mentioned the Diamond Hoax of 1872. But this is by no means the only fraud that you dig up in this book. There’s Samuel Adams — no relation to the beer, no relation to John Adams’s second cousin — he came close to milking $20,000 from Congress for an expedition he claimed he made in Colorado. William Gilpin claimed that two billion people could easily be accommodated in the Western Territory.

Winchester: Two billion. Please note that.

Correspondent: Yes. Two billion.

Winchester: Not million, but billion!

Correspondent: Yes. Exactly. The folly of New Harmony, with David Dale Owen. Is it safe to say that many of these efforts to unite America required a crazed belief culture or possibly a set of existential blinders with which to achieve ambition?

Winchester: Well, I have to hold you there. Your reference to David Dale Owen and to New Harmony. I actually think New Harmony was a story very creditable in American history. Just very briefly, this is a little town at the confluence of the Wabash and the Ohio Rivers. Initially, it was a utopian settlement built by a group of Suebians, Germans who were being persecuted back home. Very similar to the Pilgrim fathers and all that. They prospered. They sold this little community to the next utopian who came along the line, who was a man called Robert Owen. And he intended to build a community of fiercely intelligent intellectuals who would use it as a base for proselytizing intelligence for teaching. And he lured a number of Philadelphia intellectuals — most notably, a man called William Maclure, who drew the first ever geological map of this country in 1809, I think it was. And they all came down from Philadelphia by way of Pittsburgh on a boat, which was called the Boat Load of Knowledge and joined Robert Owen and set up this little settlement. Now it is true to say that the settlement, like so many utopian settlements, floundered because of schismatic arguments. I think there were ten subcults within about a year.

Correspondent: What amazes me was that one could get on the Boat Load of Knowledge. I mean, that name should have been the big tip off.

Winchester: You would have thought so. The Boat Load of Extreme Pretension.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Winchester: But nonetheless David Dale Owen, who was the son of Robert Owen and who was taught geology by this man Maclure, went on to become a real evangelist for early geology. And I know that geology in this country is ill-regarded. I try and do my best to get people to say that it was a great deal more than Rocks for Jocks. It quite literally underlies everything we can see in this room today. The metal for your tape recorder, the television, the paper, the paint, the wood. Everything comes from the earth as a result of geology. He, David Dale Owen, essentially started the Geological Surveys or triggered them in some way in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota. So the mapping and the discovering of the mineral wealth of these states could all be put down to the efforts of New Harmony. So I would completely repudiate your idea that in any way that that’s a scam. It failed.

Correspondent: A belief scam, I thought.

Winchester: Yes. A belief scam. I couldn’t agree with you more. But in terms of its legacy, it’s a very important place. And it is a shame — and I’m going to sound rather sort of not belligerent here, but I just think that it is a shame that more people don’t know of New Harmony. And it should be a shrine to the early phenomenon of learning in this country. It’s a very important place.

Correspondent: It’s interesting that you’re more pro-New Harmony and not so much Paradise in this book. That’s interesting. Since you had mentioned geology — and as an American, well as a fellow American, geology is not exactly one of my best spots. But I do want to discuss the Eastern American Fall Line and the Hudson-Mohawk Gap. Much of American settlement owes its existence to these two geographical realities. Explorers fell into this natural expansionist rhythm when pushing against this. But I’m wondering to what degree were the explorers aware that they were kind of fulfilling almost a geopolitical destiny here.

Winchester: I can safely say that none of them imagined. It is conceivable that in the construction of the Erie Canal there was a thought given to the geopolitical consequences. But let me just explain. All the people who you’ve talked about or alluded to journeyed into the interior of America from the Eastern settlements by river. And as you sailed and counted after fifty, sixty, ninety miles of paddling, suddenly the waters got rougher. There were waterfalls. There were rapids. Their progress was blocked. So they had to stay there and have a settlement from which they would portage. And those settlements eventually became cities. Richmond, Fredericksburg, Washington D.C., Albany. Then to circumvent those rapids, and to allow those communities to trade with the interior beyond the Appalachians, the settlers had to build primitive canals. So they learned how to build canals. They then, once they realized the economic importance of canals, once they had learned the technology of constructing them, then they started this mania of building them all over the country to connect places where there were minerals or work or whatever with the nearest ports. So that the Middlesex Canal in Southern New Hampshire led to the creation of the expansion of Boston. The important one — and this is where your geopolitical question, I think, comes to the fore — was the one that linked Buffalo to Albany through the Hudson-Mohawk Gap, which all of us at school in England when we were eleven years old had to know the significance of the Hudson-Mohawk Gap in world history. Because once that gap was filled with the canal and once trade could be brought theoretically from Lake Superior, Hudson, Lake Huron, Michigan, to the port Buffalo, taken down the Erie Canal, turn right and go down to New York City, then this allowed New York to prosper in a way that no other American city did at the time and to become a world port. The man who had the idea for the Erie Canal, which is the name of the canal between Buffalo and Albany, was a man called Jesse Hawley. And Jesse Hawley was a highly intelligent farmer in Canindaigua, New York who could not get his wheat down to the bakers in New York because the little canal that existed in the Mohawk Gap charged such extortionate rates that it actually drove him bankrupt. Drove him to debtors’ prison. He sat in a debtors’ prison for many months and, while there, studied European canals. Because he said, “What we really need is something that isn’t extortionately run which is a canal between Buffalo and Albany.” So he wrote the local newspaper called The Genesee Messenger from his cell in the debtors’ prison under the pseudonym “Hercules.” Fourteen extremely well-argued essays saying that if you, the State of New York, build this mighty canal, not only will you give New York City prosperity, but you will change America’s standing in the world. These essays were read by the then Governor of New York State, Governor Clinton, and he said, “This man Hercules, whoever he is,” — he had no idea he was in a debtors’ prison — “is right.” And he got the money through the Legislature. And the Erie Canal was built. And the first person to attend the ceremony of the wedding of the waters, where the Great Lake’s water was dipped into the Atlantic Ocean at the Verrazano Narrows, where the bridge is there — the first person to pour the first water was Jesse Hawley, now free from the debtors’ prison, who had this brilliant idea. So I’m certain that he, and probably he alone, had an idea of the geopolitical importance of the canal.

Correspondent: Got it. Well, while we’re on the subject of canals, I have to bring up the Chicago Sanitary Canal. The Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal to be quite precise. This was an engineering effort in the late 19th century to quite frankly rid the rapidly growing Second City of its escalating shit. Now 99% Invisible, this wonderful radio program, happened to actually do this wonderful show on the canal back in August, and host Roman Mars pointed out how Ellis Chesbrough — this Boston engineer now forgotten to history — was responsible for this canal and he had the audacity to jack up the street level in Chicago up ten feet. It took twenty years. It was amazing. But you didn’t mention Chesbrough at all. And I’m wondering about this. You claim that this guy Isham Randolph was the guy who came up with the Chicago Sanitary Canal. So why didn’t you include Chesbrough? And I’m wondering what research you relied on for the Chicago Sanitary Canal?

Winchester: Well, that is a good question. Principally, the editing process of this book — and I’m not blaming anything on the editor at all. When I turned in the manuscript, which was for 150,000 words — that was the contract — it was 195,000. Because I had found so many ancillary personnel, of whom Chesbrough was clearly one. He didn’t have the idea for the Canal. Isham Randolph was the central figure in the building of this canal. Chesbrough did, yes, that’s why when you go down Wacker Drive, all the underneath, that’s all part of Chesbrough’s achievements, which are laudable, but quite reasonably, I think, we had to strip down — and I remember I was in Bangkok in Thailand — and my editor said, “Look, Simon, this is wonderful. It’s full of wonderful stuff. But we’ve got to eliminate some people. Some ideas.”

Correspondent: (laughs) We’ve got to assassinate a few of them.

Winchester: We do. And I make no apologies for it. The book has got to be a manageable length. And you, I dare say, will come up with other people who you can say in an accusatory way, “Why did you leave him out?” Well, I’ll say, “I’m sorry. Life needs to be edited.” And so Isham Randolph to me is the important character. The other one, not so.

Correspondent: Well, what 99% Invisible pointed out was that Chesbrough didn’t even have a Wikipedia entry.

Winchester: (laughs)

Correspondent: And how he was just completely cut out from the great story of the Chicago Sanitary Canal! And I’m wondering. The sense I got, at least from that segment and from a few other things I read, was that actually Chesbrough was the real deal. And you say he’s not. And I’m wondering what books and what scholarship say that Randolph is the guy rather than Chesbrough.

Winchester: Well, the history of the Chicago Canal by a lady who, I think, her last name is Kelly. I don’t have the bibliography in front of me at the moment. [NOTE: Winchester’s bibliography lists Libby Hill’s The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History. This is likely the book he consulted.] And my friend, and the husband of my agent, who has written a book called The Third Coast about the development of modern Chicago. The history of the Armour Meat Company. Upton Sinclair’s book on Chicago, which I’m sure you’ll remember the title.

Correspondent: Yeah. The Jungle.

Winchester: The Jungle. All of these taken together helped me in this late 19th century, early 20th century construction of Chicago. And if they don’t mention Chesbrough, then I don’t mention Chesbrough.

Correspondent: Even though the newspapers of the time mention Chesbrough.

Winchester: I am not going to sit here and justify every omission in this book.

Correspondent: Alright.

Winchester: There are bound to be some people who are going to fall by the wayside. It’s like being cut and ending up on the cutting room floor. I’m in no way defensive about it. I’m simply saying that, in my view, Isham Randolph was the more important figure.

Correspondent: Okay. Well, I was curious how you came to that view.

(Loops for this program provided by sintheeticrecords, proecliptix, leoSMG, boogieman0307, and progressbeats5.)

The Bat Segundo Show #527: Simon Winchester (Download MP3)

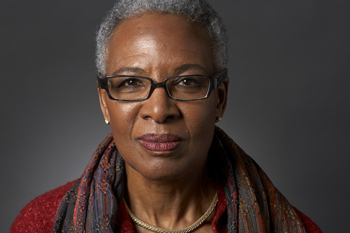

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”