Listen: Play in new window | Download

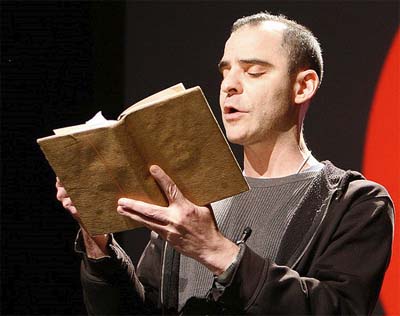

On December 5, 2010, the Irish novelist Paul Murray encountered one of Mr. Segundo’s many agents before a full audience at Word Brooklyn. The two gentlemen proceeded to talk, with smart audience interjection and Mr. Murray reading from the book, for a little under 90 minutes. Just as the tape ran out, the very patient Word Brooklyn staff wisely put an end to this gabfest. The two gentlemen had no idea they had rambled on for so long. From all reports, neither did the crowd.

The first part of this conversation is now available for your listening pleasure as The Bat Segundo Show #370 (also referred to as “Phyllis Presents,” for reasons known only to those possessing the appropriate handbook). It is about 41 minutes long and involves the initial Q&A between Mr. Murray and our most mysterious agent.

The second part of this conversation is now available for your listening pleasure as The Bat Segundo Show #371 (which does not possess any alternate name, we are sorry to report). It is about 38 minutes long and features Mr. Murray reading from his latest novel, Skippy Dies, along with further questions from our agent (and many from the crowd). If you listen carefully to this second part, you may be able to detect a broken haiku.

The producers wish to thank Brian Gittis, Stephanie Anderson, Jenn Northington, Sarah Weinman, and (of course) Paul Murray for their great assistance (much of it at the last minute) in making this special conversation happen. We hope to offer similar “live” conversations in the future.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Recoiling from the pleasures of being applauded by a recorded audience.

Author: Paul Murray

Subjects Discussed: The influence of cinema, Gene Tierney, Glengarry Glenn Ross, the “Intelligent Eye” system, constructing a soundtrack for life, characters who flee reality, Anthony Lane and the Beijing Olympics, the camera increasingly pervading existence, Murray’s hero worship of David Lynch, balancing audience demand for traditional logic with shocking character revelation, Twin Peaks, not making sense as a bold aesthetic move, David Lipsky’s Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, Lynch vs. Pynchon, David Shields’s Reality Hunger, excavating the old in the quest for new fiction, Tristram Shandy, the importance of having a big nose, gutting from reality, Russell Hoban’s “feeling unreal is an essential part of reality,” mid-century Irish naturalistic writers, Irish fiction’s failure to interrogate modernity, video games as a teenage refuge, gamebooks of the 1980s, the Walkman as a shift in the way we perceive reality, The Legend of Zelda, Team Fortress 2, Shigeru Miyamoto, computer games and narcissism, Skippy Dies‘s slips into second person, the frustrations with maintaining a dimwit first-person perspective in An Evening of Long Goodbyes, the Celtic Tiger, writers and bank statements, the unexpected rise of phones in Ireland, lattes in Ireland, working in a cafe without comprehending focaccia, Dr. Seuss’s The Sneetches, ineffectual use of outdoor jacuzzis in Ireland, property fairs, Robert Graves and the Great War, Gallipoli, World War I Irish involvement erased from the history books, the Church and child abuse, Michael Durbin of The Irish Times, derivatives, and whether the novelist is guilty in ignoring certain narratives while coating reality within a fantasy.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Murray: It needed to be structured in a way that wasn’t linear and that wasn’t naturalistic. Because I just don’t think like that. I wasn’t trying to be experimental. I just thought that, if you are a kid nowadays, your life is not very linear and it’s not very naturalistic. Because you’ll spend most of your time looking at your phone or looking at a screen. Or watching the TV. You’re very rarely actually where you are. Do you know what I mean? I guess maybe that’s part of the human condition. Never to be actually tuned into what’s around you. But it seems like the whole thrust of the 21st century is just to take us further and further and further away from where we are. And further away into strange digital fantasies.

Correspondent: And this probably explains why so much of Skippy is about this meshing between reality and fantasy. That, in your efforts possibly to examine life with these delimiting technological factors, you’re saying that it led inevitably to this blur between reality and fantasy?

Murray: Yeah, I think that’s what you do when you’re a kid. As I say, when I was a kid, there was no Internet. And computer games — I wasn’t quite Pong era.

Correspondent: Asteroids maybe.

Murray: Yeah. But I think the teenage — the way you kind of cope with the stresses of being a teenager is to take refuge in TV shows or films or computer games. Like I was really into those — well, I wasn’t into role playing. But there were these gamebook things.

Correspondent: Oh yeah.

Murray: Where you rolled the dice and fought orcs.

Correspondent: Yeah. Like the Lone Wolf books?

Murray: Yeah! Yeah! Totally!

Correspondent: I totally played those. They were great.

Murray: Don’t tell anyone.

Correspondent: It’s on tape, I’m afraid.

Murray: Ah! Again with the orcs! Oh no! When are the orcs going to get along?

Correspondent: I know.

Murray: That’s what you do. You’re constantly — like when I was growing up, the Walkman arrived, you know? And I’m going to argue that the Walkman is a major shift in the way we perceive reality. Because for the first time, you can carry music around you. And you start narrating your life. Like the self-narration just shifts gear. Shifts higher up. And that kind of process is — as I say, what technology gives us is more and more elaborate ways of doing that. So the kids in the book, because they’re young and they’re afraid and they’re lost, they take refuge. The big example is Skippy. Skippy’s this fourteen year old, quite reclusive boy who is addictively playing this computer game. Kind of a Legend of Zelda-like computer game. And have you ever played?

Correspondent: Zelda? Yeah, yeah. That thing sucked too many hours out of my life.

Murray: Yeah, it’s crazy.

Correspondent: Now it’s Team Fortress 2. If we’re going to be professional.

Murray: Yeah?

Correspondent: Oh yeah. Oh god.

Murray: Okay. We can talk about this later.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Murray: I mean, I’m not a huge computer games player. But my brother had a — whatever the machine was to play Zelda.

Correspondent: NES.

Murray: And it’s the same guy. The same game designer. The guy who invented Donkey Kong back in the ’70s has now done Legend of Zelda. And he creates these incredible worlds that are so powerful and are like art forms in some ways. In the richness of detail and in the beauty of them. But they’re not like art forms in the fact that they don’t challenge your perception. They don’t challenge you as a person at all. They make you like the master of this world that you find yourself in. Which is like a really narcissistic kind of fantasy. And the kids lose themselves in these fantasies of control and power. You know, like the same way if you walk down the street and you’re listening to Tupac, you kind of imagine that you’re Tupac. And even if you’re fourteen and very small, if motherfuckers come at you, look out. So that’s what you’re doing. I guess the really obvious conceit of the book is that that’s what everybody’s doing these days. That as an adult, being an adult or being mature is less and less part of the adult experience. Instead, being old and adult is someone with more spending power who can buy better enhancers or escapes from reality. Part of the reason the world is so — I’m trying to say fucked — is because we feel less and less responsibility for the world around us. Instead we’re just fleeing into whatever Apple has just produced and for a thousand dollars.

The Bat Segundo Show #370: Paul Murray, Part One (Download MP3)

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?