It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

— Philip Larkin, “A Study of Reading Habits

Each person has a different approach to reading. Some folks read in ten minute chunks. Others read in three hour clusters. Some read daily. Others read every week. Some read only nonfiction. Others read only fiction. Some read only on the toilet. Others need to be sitting nude on a mat, preferably in a yoga position for maximum meditation. Make up your own dichotomy and throw it into the pile like a pair of used cufflinks.

The very real question I have, inspired by this anecdotal post at the Shifted Librarian on how game culture has shifted productivity patterns, is whether any approach to reading is wrong, or whether the act of reading itself should even be concerned with something that smacks of schoolmarm etiquette. (These guidelines, for example, suggest that vocalizing or moving lips while one reads is bad. I must therefore conclude that every so often, particularly when I am perusing something that begs to be vocalized, I am a very bad reader indeed.) After all, since we’re talking about an act that is largely solitary, my gut feeling is that the only person who should be concerned with the question of the right way to read and the wrong way to read is the reader herself.

Greogry Lamb has suggested that computers have changed the way that people read, but his article dwells more on how people are learning to increase their WPM reading rate (or using reading supplements like highlighting tools, including a site being devised by the Palo Alto Research Center to annotate Hamlet with endless scholarly commentaries). It says little about, say, the nauseating sensation of reading a 100,000 word novel on a computer screen (as opposed to a 2,000 word essay, which is more managable for the eyes and head) — a prospect that is likely to change as displays come closer to resembling paper (both in feel and resolution). (Many of these developments are being chronicled at the excellent Future of the Book blog.)

Since magazines and newspapers are seeing their subscriptions slowly plummet (with even such one-time staples as TV Guide resorting to drastic overhauls), there is the additional question of whether reading, at least as it pertains to magazines and newspapers, has adopted a time-shifting quality that we have been more willing to attribute to TiVo and podcasting, but that we aren’t willing to apply to articles. This strange stigma may have something to do with the fact that much of this reading is done on company time, whether through the reader sitting at her work desktop reading an article in its entirety or disguising this malingering through effective one-browser window aggregators such as Bloglines or printing it off using company paper to read it on the subway home. Who wants to mention this when it’s legitimate grounds for a grievance?

In other words, technology has enabled a remarkable workforce cluster to read by subterfuge (possibly for short-length articles). Perhaps they read because it’s a revolutionary act that, outside of web tracking software, can’t be completely gauged — sort of like jerking off on the clock.

Despite these clear advantages, there still remains a remarkable faith in technology which might be out of step with the tactile advantages of reading books, to the point where undergraduate university libraries have pared down their books to a mere 1,000 volumes and it is now inconceivable for today’s college students to leave home without an arsenal of technology.

But if libraries and educational institutions become based almost solely around technology, where lies the future of reading? While there are plenty of studies indicating that reading is dropping and there remains some debate over whether this is a “sky is falling” alarmism (which Kevin Smokler and Paul Collins challenge in Bookmark Now) or a problem that needs to be addressed, none of these studies seem to indicate, to me, a much more telling trend: what type of reading are people doing precisely? Do they prefer shorter content such as a 2,000 word essay or a short story? Is there a correllation between a proclivity to read things on the Internet and the drop in “reading literature” announced within NEA’s “Reading at Risk” report? Certainly, the ascent in chapbooks such as Harry G. Frankfurt’s On Bullshit to the bestsellers list cannot be entirely overlooked.

If shorter reading experiences are the future (in part or in whole), then I would suggest that the short story has a fantastic new life ahead and that The Atlantic Monthly, in dropping short fiction entirely from its pages (and in failing to allow non-subscribers to access their content), is ass-backwards. Big time. Unless of course they see a new market in chapbooks or content siphoned directly to today’s tech-savvy reading base.

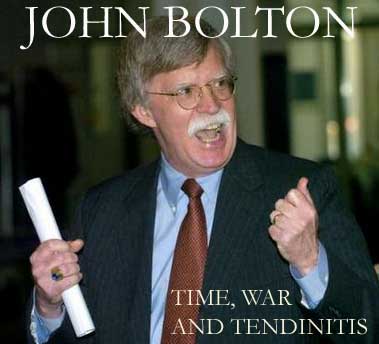

His chief collaborator this time around is former Republican Justice Earl Warren, whose death in 1974 did not preclude Bolton from sifting through Justice Warren’s treasure trove of bad poetry and hastily written lyrics. Warren penned half of the songs on this album and his passion for that old-time war hawk feeling can be heard on the album’s highlight track, “When a Man Loves a Weapon,” a loving paean to both the cold war and unilateralism.

His chief collaborator this time around is former Republican Justice Earl Warren, whose death in 1974 did not preclude Bolton from sifting through Justice Warren’s treasure trove of bad poetry and hastily written lyrics. Warren penned half of the songs on this album and his passion for that old-time war hawk feeling can be heard on the album’s highlight track, “When a Man Loves a Weapon,” a loving paean to both the cold war and unilateralism. So according

So according