THE SEED COLLECTORS

by Scarlett Thomas

Canongate, 384 pages

(UK only, unavailable in the United States)

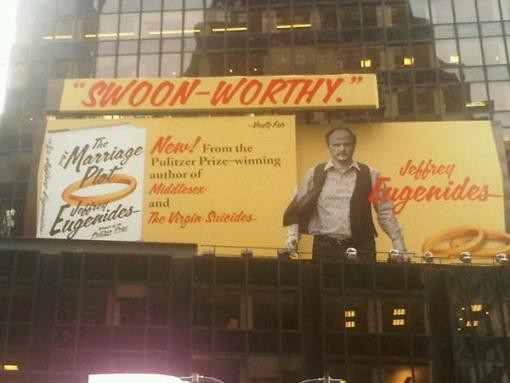

A little more than a decade ago, fiery ambitious fiction was in something of a crisis. Time-taxed readers flocked to meliorative middlebrow, thrilled to have their middle-class worldviews confirmed by authors too paralyzed to take real chances, but pretending to be prodigious talents. Remarkably mediocre novelists like Julia Glass actually won distinguished awards for pounding out sappy pablum. Jennifer Weiner — the Michael Moore of literature — conned smart readers (including this one) into believing that her privileged pink-covered rubbish was as meritorious as such deservedly popular authors as Stephen King, Laura Lippman, Megan Abbott, and Richard Russo, befriending the right people to ensure that her formulaic tales were vaguely perceived as “literary.” Before he found appropriately mercantilist stature on a Times Square billboard, Jeffrey Eugenides preyed on progressive naiveté with Middlesex, his big fat Greek wedding of a novel, using transgender symbolism to deliver a epic that was only as sweeping as the hot air blowing against his vest, even as he doled out references and metaphors that, as Sarah Graham has smartly argued, were complicit in the exploitation he seemed to be railing against. Michael Cunningham entered this scene like Isaac Pocock carving up Waverley into bits of melodramatic balderdash, braying about happiness contained in a kiss and a walk and sealing the illusory import with the portentous inclusion of Virginia Woolf. It was no surprise that Cunningham’s treacly Madison Avenue nonsense (“It’s the city’s crush and heave that move you; its intimacy; its endless life.”) was adapted into a pretentious film scored by Phillip Glass. Ask any dependable reader today with any self-respect about The Hours and she will give you the look of a shellshocked Frenchman still taking in the miracle of surviving the First Battle of the Marne. Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones, was a YA book before its time (“Sometimes the dreams that come true are the dreams you never even knew you had”) that practically demanded a string section to accompany its condescendingly pat narrative.

In one way or another, these authors produced fiction that was wrongly perceived as different and ambitious. (The Lovely Bones: “refreshingly experimental, and ambitious in the extreme.”) They believed that ambition was not so much a burning drive to stir the hearts of readers, but a buzzword that could cover their lumpy noggins like a borrowed chapeau. But none of their crass careerist efforts held a candle to the most entitled and pampered literary huckster of them all. Jonathan Franzen, rightly condemned by Ben Marcus as “against the entire concept of artistic ambition,” presented himself as a subversive by defying Oprah even as he renounced his experimental roots with The Corrections. Yet Purity, his latest barking dog of a novel, is despicably Republican-minded and unrealistic in its treatment of women. Nearly every female character is sexually assaulted, sexually humiliated, inexplicably serves up her body to an older man (and often apologizes for it!), uses her body to get ahead, is defined more by flirtation than the prowess of their minds or the depths of their souls, and, if sex isn’t an option (because apparently older people don’t fuck in Franzen’s universe), is considered crazy or bipolar. (Indeed, one of Purity‘s characters, Anabel spends many years working on a film about the female body, as if this is the only topic that a struggling woman artist is meant to explore.)

All these novelists had to do was bang you over the head with a traditional narrative that ran way too fucking long and — voila! — marketing forces could turn these dithering Pollyannas into putative literary titans.

In fairness, people probably sought comfort reads, much as they always do in tragedy, in 9/11’s immediate aftermath. In recent years, the major literary awards have redressed concessionary wrongs, recognizing fierce and original talents like Jesmyn Ward, Jaimy Gordon, Paul Harding, Junot Diaz, Edward Jones, and Adam Johnson. Bold websites such as the regrettably departed HTML Giant kept the flame alive for the quirky, experimental, and small press titles, with the legacy continuing today in spurts. Yet the reductionist symphony of Goodreads groupthink, Slate clickbait (“Can a public intellectual speak for us all in an era of fragmented culture?” reads one recent subhed, as if meaningful intellectual argument involves universal concord) and Book Riot circlejerks (“If Shakespeare Plays Were Fast Food Chains” and “The Therapeutic Effects of Reading Middle Grade Fiction as an Adult” read two Book Riot posts) belie the same childish, unambitious, and risk-averse hydra that buttressed Claire Messud’s spirited response to a foolish question about “unlikable” characters. Today, the reading comprehension problems cited by Jack Green in 1962 in relation to William Gaddis’s masterpiece, The Recognitions, are now applicable to only remotely “difficult” books. When Mark Z. Danielewski outdoes Knausgaard with The Familiar, an ambitious and visually striking 27 volume project that works to tell its story in a challenging manner that is perhaps only an eighth as “difficult” as William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, a professional jackass declares the first installment “unreadable” rather than comprehend the book on its own terms. While great novels such as Hanya Yanagahira’s A Little Life have changed the rules on how to depict abuse in contemporary fiction, one cannot gainsay the clunky magazine-style prose used to push forward the message. Today’s young authors are so desperate to please and so fearful of social media recriminations that their books are more likely to feature predictably escapist tales with likable characters.

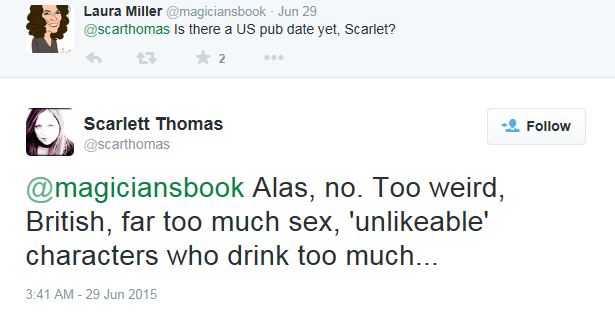

But there is one author who may very well be our great hope out of this predicament, if people are willing to read her. Much like Richard Powers, Scarlett Thomas is one of the most unsung novelists working in literature today. Her extraordinary new novel, The Seed Collectors, is smart, funny, willing to explore all sides of thorny moral and intellectual questions, and defiantly working against reader expectations even as it grabs the reader by the lapels. Yet no American publisher has the stones to issue her book on this side of the Atlantic.

When Scarlett Thomas’s The End of Mr. Y arrived in the United States, it was rightfully heralded among hardcore Yankee readers as as the arrival of a major talent: someone who didn’t see literary and genre as working against each other, yet someone also determined to fuse fun and thought with a realm known as the Troposphere, whereby people could enter into a unified consciousness and dance with the thoughts of others. Thomas followed this novel up with Our Tragic Universe, an equally extraordinary volume that was foolishly derided by Thomas’s professed boosters as “[relying] on the two laziest storylines the world of fiction has ever thrown up.” What Thomas’s sudden apostates couldn’t seem to understand was that this thoughtful author was using coincidence and predictability, not unlike David Foster Wallace investigating boredom in The Pale King, to create a rich portrait on what it is to live a life when we are surrounded by endless structure:

A couple of years before, I’d sat on my father’s lap and asked him what he did all day at the university. He told me that he spent most days looking at numbers and doing calculations in order to try to find out how old the universe was. He said his whole job was like being a detective where you look at clues and find out what things are made of or how old they are. I asked why he wanted to know how old the universe was, and he said that was a good question, but a difficult one. I remembered something from school assembly and suggested that perhaps he wanted to know more about God, and his smile died and he put me down on the floor and told me it was time for bed.

Published in 2010, when we were only just starting to understand how social media’s liking and favoriting was hindering unpopular or less glamorous content, reducing the wonders of curiosity into quantified binaries devoid of nuance, Our Tragic Universe was not the big American breakout hit that its publisher hoped it would be, perhaps because it adamantly refused to kowtow to the trite pleasantries that American readers were increasingly becoming drawn to.

The Seed Collectors is the first book I’ve read in a very long time that not only has its finger perspicaciously on the pulse of our anxieties and afflictions, but that challenges the notion of family structure and the way in which we push forward our best selves. It is ambitious not necessarily because of its form (although the number of thoughts that Thomas contains within less than 400 pages is quite phenomenal and makes the novel difficult to describe), but in the way that it unites numerous observations into a Weltanschauung that the smart reader will feel compelled to argue with. To a certain degree, The Seed Collectors is almost a referendum on the early Lily Pascale mysteries with which Thomas established her literary career (and which she no longer lists in her credited works). The engaging Lily Pascale trilogy, which is hardly as egregious as Thomas would have you believe, was as much about exploring whether normalcy and family could serve as acceptable panacea as it was a trio of gripping yarns about murders and psychedelic cults leaving inexplicable imprints on small communities. But now Thomas is a wiser and more adroit writer, nimble enough to take on a remarkably broad range of subjects in one go — what we don’t hear when people are telling us their most intimate thoughts, body image, toxic masculinity, gamification, porn, thwarted career ambition, botany, travel, online shaming, interpretive rigidity, and numerous other topics — even as she spins an elaborate story involving a vast and variegated family drawn together by the recent death of a beloved matriarch who has left a collection of mysterious seed pods to her many scions.

The novel’s considerable dramatis personae represents a wildly vast cross-section of contemporary life, yet it is a great testament to Thomas’s extraordinary talent that we come to know all these characters quite vividly. Bryony Gardner is, to a large degree, the book’s conflicted heart: an overweight alcoholic who, not unlike Our Tragic Universe‘s heroine Meg Carpenter, ponders whether her marriage and her life is all that it’s cracked up to be. If The Seed Collectors had been written by Jonathan Franzen, Bryony’s needs would have been ridiculed or belittled. If The Seed Collectors had been written by Jennifer Weiner, Bryony would become a superficial plus-size stereotype squeezed into a predictable story template. But Thomas is too good and too humane a novelist to wince away from Bryony’s inner world. Despite Bryony’s extraordinary behavior, we come to empathize with her because she is always measuring her calorie intake and her weight against fears that she is not cut out for normal life, whatever that might be. Her three glasses of champagne after an afternoon tea and her casual eating binges are part of a full-bore commitment to excess and entertainment, an imposing pit that anybody can fall down in our age of instant gratification and casual swipes of the credit card. Bryony thinks about an ugly man following her into a train restroom and becomes alarmed at how her fantasy alters into something grotesque as she masturbates. “Your job was not to CHOOSE Holly’s birthday present,” says Bryony to her husband midway through the novel, “just to collect it.” And with the purchase of this tennis racquet neatly compartmentalized, we come to wonder whether Bryony’s impulsive and often quite specific consumption habits could be remedied if she had the guts to place her stock in warm nouns rather than cold verbs.

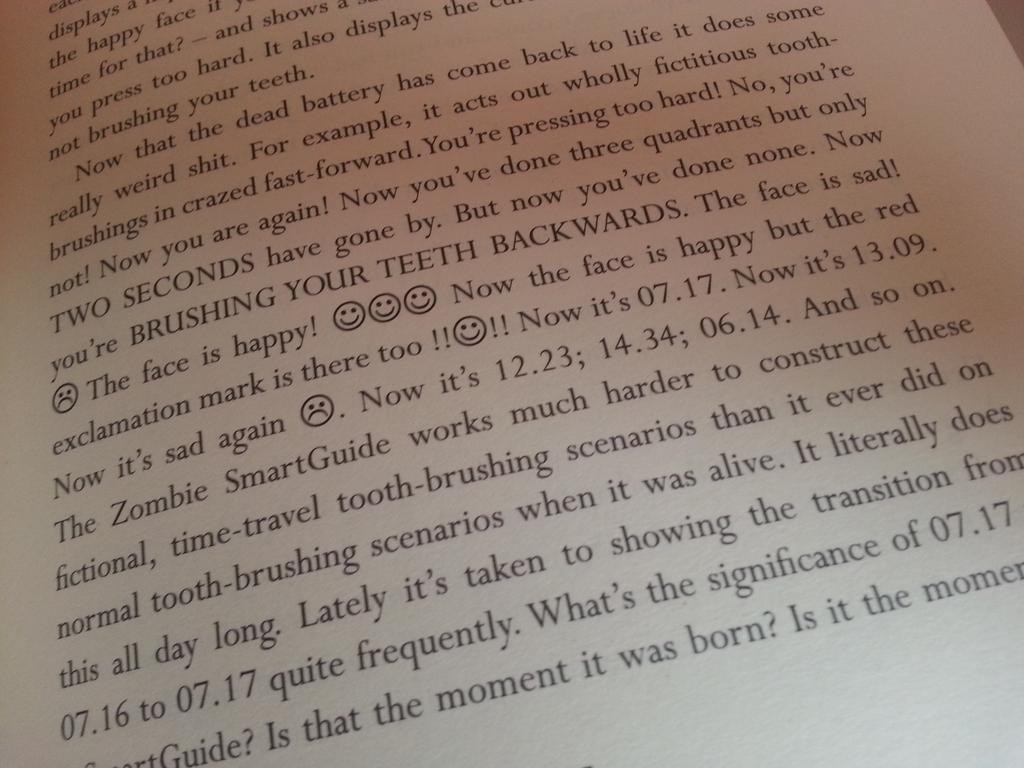

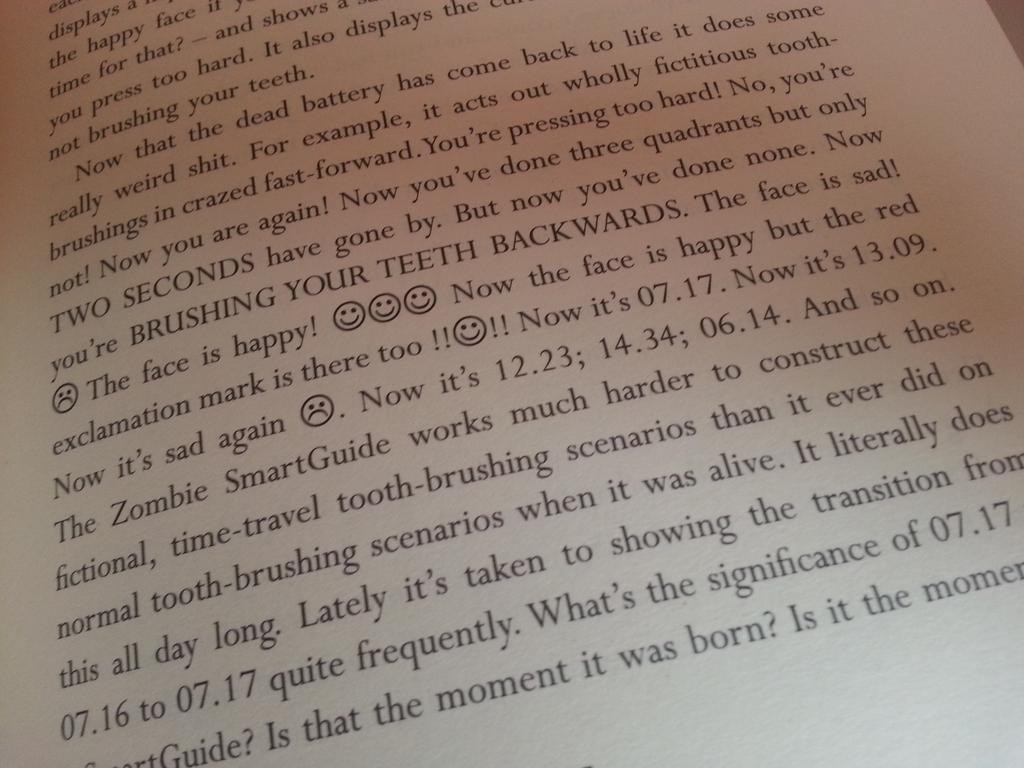

To a large degree, The Seed Collectors is holding up a very large mirror to the Quantified Self movement, whereby everything we do in this world creates data, collected and hawked and redistributed in ways that are not necessarily compatible with our complex feelings. The above passage, a glorious pisstake on gamification, sees Ollie, a man who Bryony is considering sleeping with, at the mercy of an Oral B Triumph SmartGuide, an alarmingly horrific (and quite real) device that demands its practitioners to brush teeth in highly specific ways, with emoticons rewarding a commonplace activity with Candy Crush-style perdition. Even a monstrous man named Charlie, who is introduced sexually violating a blind date before the thirty page mark (perhaps another reason why American houses lack the spine to publish this book), is someone who clings to a list of attributes that he’d like to see in “my perfect girlfriend.” And if quantification is the deadly condition uniting all these characters, then how do these disparate characters live? As the novel progresses, Thomas introduces a great deal of dialogue in which the speakers are never identified. And this missing data, so to speak, steers the reader towards an emotional intuition well outside any data subset. And as Thomas serves up more twists and revelations, we come to understand that it is still possible in our age of unmitigated surveillance to be attuned to our private thoughts (though for how long?). The novel, which we have believed all along to be thoroughly structured, has perhaps been a lifelike unstructured mess all along. And this unanticipated alignment between fiction and our data-plagued world feels more artful and poignant than such conceptual stunts as writing a short story composed entirely of tweets. It makes The Seed Collectors almost a cousin to Louisa Hall’s recent novel, the quite wonderful Speak, which used a computer algorithm to determine which of its five perspectives would be on deck next. But even if you don’t want to play this game of six-dimensional chess, The Seed Collectors still works as a sprightly narrative on its own terms, at times reading like an Iris Murdoch novel written for our time and beyond.

But the forces that be will not publish The Seed Collectors in America. They have remained distressingly resolute in recoiling from any book, even one as enjoyable as The Seed Collectors, that understands that readers have brains and are worthy of being respected and challenged. This is a pity. Because The Seed Collectors proves that a great novel can be poignant, ambitious, artful, and a bit punkish.