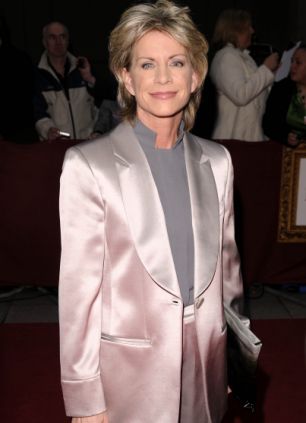

Patricia Cornwell appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #257.

Patricia Cornwell is most recently the author of Scarpetta. This interview serves as a companion piece to Sarah Weinman’s Los Angeles Times profile.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Checked in for narcissistic personality disorder.

Author: Patricia Cornwell

Subjects Discussed: The genesis of Kay Scarpetta after three unpublished novels, Sara Ann Freed’s input into Cornwell’s early career, on being rejected by the Mysterious Press, Susanne Kirk, the unexpected success of Postmortem, how Charles Champlin’s Los Angeles Times review changed the publisher’s perception, writing a Scarpetta book before the last one was published, switching from first-person to third-person midway through the series, tinkering around in the movie business, being unable to write anymore in the first-person perspective, on later books lacking the warm element of character interaction, trying to get better through experimentation, listening to fans and readers, bringing back Benton Wesley from the dead, the differences between Cornwell and Scarpetta, writing sex scenes, privacy and reluctant fame, reporters who have the temerity to follow Cornwell into the bathroom, cops and submachine guns, Ab Fab, Judd Apatow’s films, Cornwell’s continued involvement with forensic science, taking out full-page ads to correct being misquoted by a journalist, pursuing the Jack the Ripper case, making various investments, surviving in the dour economy, and Cornwell’s political involvement.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: What’s interesting too is that your career essentially started at the behest of very legendary people in the mystery world.

Correspondent: What’s interesting too is that your career essentially started at the behest of very legendary people in the mystery world.

Cornwell: Right. That’s right.

Correspondent: And then Susanne Kirk found it at Scribner and picked it up from there.

Cornwell: And she was quite a champion for it. Because the publishing house, from my understanding back then, was very dubious about it. This was so different. Nobody wrote books like this back then really. First of all, you had a serial killer who was a stranger to the victims and a stranger to everybody. And the tradition of “mysteries” is that it was someone in your midst. And there were so many traditions that were shattered. Because real crime shatters those traditions. And I was writing about what I saw, and really taking a journalistic point of view. Although I was weaving it into fiction. And some of the rejection letters were “Nobody wants to read about morgues or laboratories.” And certainly not a woman who works in an environment like this and sees what she does. It seems silly now. But back then, that just wasn’t done.

Susanne though had the futuristic vision to think, “This is new and different. And this is pretty cool. And I want to publish this book.” But she had to have yet another opinion. She had to have another person read it. And they deliberated. And they just barely decided. In fact, the telephone call I got — the famous telephone call that changes your life — it was iffy. It was “We think we’re going to publish Postmortem, but we want to get one more person to read it.”

Correspondent: So it had to go to the editorial board in other words.

Cornwell: It was actually an outside consultant they had. Someone they considered an expert. A man, whose name I don’t remember. And they needed one more person to look at it to see if they really were going to do this. And that was my great turning point. My telephone call was a maybe. And then they did decide to take it on. But it was a very small printing. 6,000 copies. $6,000 is what I got paid. No advertising. No marketing. No nothing. And by the time people discovered it, it was out of print in hardcover.

BSS #257: Patricia Cornwell (Download MP3)

Correspondent: Golf figures prominently into a number of these stories. In “How Much Greater the Miracle,” you write, “The soul and golf are interrelated. I try not to wax too philosophical, but the soul is like a golf ball.” Now is this particular statement one of the reasons you frequently return to golf in your writing? Do you feel that golf gets a bad rap? Is this your way of essentially taking it, or absconding it, from the upper-class country club associations? Are you trying to counter the John Updike/Richard Ford/Kevin Costner kind of approach to golf? I think this is a very important question!

Correspondent: Golf figures prominently into a number of these stories. In “How Much Greater the Miracle,” you write, “The soul and golf are interrelated. I try not to wax too philosophical, but the soul is like a golf ball.” Now is this particular statement one of the reasons you frequently return to golf in your writing? Do you feel that golf gets a bad rap? Is this your way of essentially taking it, or absconding it, from the upper-class country club associations? Are you trying to counter the John Updike/Richard Ford/Kevin Costner kind of approach to golf? I think this is a very important question!

Instead of the backstories associated with this disastrous local theater run, we see Leo and Kate (certainly not anything close to Yates’s Frank and April, and considerably removed from Cameron’s Jack and Rose) looking across at each other at a party. But we have no real sense in the film of why these two would be attracted to each other, and, because of this, there’s no real reason to care. It doesn’t help that the Wheeler household looks more like a Pottery Barn catalog than a middle-class dwelling in 1955. And it doesn’t help that Mendes cannot even depict two pivotal acts of carnality with accuracy. (In the Mendes universe, couples have passionless sex and finish each other off in twenty seconds without even the tiniest whimper of pleasure. This is as preposterous and implausible as Sharon Stone’s over-the-top masturbation scene in Sliver. In a narrative that demands close verisimilitude, this is an inexcusable artistic decision.)

Instead of the backstories associated with this disastrous local theater run, we see Leo and Kate (certainly not anything close to Yates’s Frank and April, and considerably removed from Cameron’s Jack and Rose) looking across at each other at a party. But we have no real sense in the film of why these two would be attracted to each other, and, because of this, there’s no real reason to care. It doesn’t help that the Wheeler household looks more like a Pottery Barn catalog than a middle-class dwelling in 1955. And it doesn’t help that Mendes cannot even depict two pivotal acts of carnality with accuracy. (In the Mendes universe, couples have passionless sex and finish each other off in twenty seconds without even the tiniest whimper of pleasure. This is as preposterous and implausible as Sharon Stone’s over-the-top masturbation scene in Sliver. In a narrative that demands close verisimilitude, this is an inexcusable artistic decision.) Leonardo DiCaprio is not that man. He demonstrates little thespic understanding of what it means to be stifled. He gives us nothing in the way of sorrow, save the cartoonish wails and the exaggerated throwing of physical objects from surfaces. DiCaprio has been relying on this ever since a few people convinced him that he was a serious actor. But he is unable to present us with some of the reasons why Frank would be tempted by an extramarital affair. He can access the territory of knowing he’s not good enough to be someone special. But when we learn how Frank Wheeler’s cavalier act gets him ahead, it is not because of DiCaprio. It is because Haythe and Mendes spoon-feed it to us ad nauseum. A scene at a beach, a scene with his co-workers at a diner, a scene with April. This is an inefficient and an insulting waste of minutes. We need not be told twice, let alone three times, that Frank Wheeler has what it takes to get ahead at Knox Business Machines. It should be self-evident in the way that Frank Wheeler acts on screen. But DiCaprio here cannot merge into the tempo established by his environment.

Leonardo DiCaprio is not that man. He demonstrates little thespic understanding of what it means to be stifled. He gives us nothing in the way of sorrow, save the cartoonish wails and the exaggerated throwing of physical objects from surfaces. DiCaprio has been relying on this ever since a few people convinced him that he was a serious actor. But he is unable to present us with some of the reasons why Frank would be tempted by an extramarital affair. He can access the territory of knowing he’s not good enough to be someone special. But when we learn how Frank Wheeler’s cavalier act gets him ahead, it is not because of DiCaprio. It is because Haythe and Mendes spoon-feed it to us ad nauseum. A scene at a beach, a scene with his co-workers at a diner, a scene with April. This is an inefficient and an insulting waste of minutes. We need not be told twice, let alone three times, that Frank Wheeler has what it takes to get ahead at Knox Business Machines. It should be self-evident in the way that Frank Wheeler acts on screen. But DiCaprio here cannot merge into the tempo established by his environment. Instead, Mendes and Haythe, who appear to be a writer-director working team about as competent as Akiva Goldsman and Joel Schumacher, see Yates’s endlessly nuanced novel as an opportunity to remake American Beauty for the 1950s, with a number of sexist nods to Mad Men thrown in for commercial appeal. “I must scoot. Toodle-ooo,” says one bubbly neighbor. And this cornball emphasis suggests that Mendes and Haythe don’t see the 1950s as a time in which real people lived and wrestled with serious decision. It is a decade to be played merely for cheap laughs.

Instead, Mendes and Haythe, who appear to be a writer-director working team about as competent as Akiva Goldsman and Joel Schumacher, see Yates’s endlessly nuanced novel as an opportunity to remake American Beauty for the 1950s, with a number of sexist nods to Mad Men thrown in for commercial appeal. “I must scoot. Toodle-ooo,” says one bubbly neighbor. And this cornball emphasis suggests that Mendes and Haythe don’t see the 1950s as a time in which real people lived and wrestled with serious decision. It is a decade to be played merely for cheap laughs.

Let us first ponder why a reprogramming along these lines is necessary. The film opens with a presidential assassination attempt with an unbelievable paucity of Secret Service agents. Later, there’s a stern judge who announces “Anyone want some tea? It’s from Greece” in his chambers at a wildly inappropriate moment. The newsroom of the fictive Capitol Sun-Times, more All the President’s Men than All the Present Realities, is utterly implausible with newspaper cuts and the Tribune Company’s bankruptcy in recent headlines. Everyone seems to have plenty of time to bullshit around in an editorial meeting. The graceful Angela Bassett almost sells her silly role as a top editor, until she urges Our Intrepid Reporter Based Heavily on Judith Miller (played by Kate Beckinsale) to get some rest, a wildly improbable request when today’s newspapers demand immediate copy to fuel sales. Our Intrepid Reporter lives in a very spacious house with another writer, who has written only one novel. (It’s safe to say that Lurie isn’t familiar with the financial ups and downs that would preclude such an affluent lifestyle.)

Let us first ponder why a reprogramming along these lines is necessary. The film opens with a presidential assassination attempt with an unbelievable paucity of Secret Service agents. Later, there’s a stern judge who announces “Anyone want some tea? It’s from Greece” in his chambers at a wildly inappropriate moment. The newsroom of the fictive Capitol Sun-Times, more All the President’s Men than All the Present Realities, is utterly implausible with newspaper cuts and the Tribune Company’s bankruptcy in recent headlines. Everyone seems to have plenty of time to bullshit around in an editorial meeting. The graceful Angela Bassett almost sells her silly role as a top editor, until she urges Our Intrepid Reporter Based Heavily on Judith Miller (played by Kate Beckinsale) to get some rest, a wildly improbable request when today’s newspapers demand immediate copy to fuel sales. Our Intrepid Reporter lives in a very spacious house with another writer, who has written only one novel. (It’s safe to say that Lurie isn’t familiar with the financial ups and downs that would preclude such an affluent lifestyle.)  Alan Alda, on the other hand, is very good as the attorney who defends Our Intrepid Journalist, even when he’s given a preposterous scenario in which he essentially whines to a judge, “Oh, come on!” That Alda can work these scenarios without diminishing his authority is a credit to his great powers as an actor. Lurie was lucky to get him on board.

Alan Alda, on the other hand, is very good as the attorney who defends Our Intrepid Journalist, even when he’s given a preposterous scenario in which he essentially whines to a judge, “Oh, come on!” That Alda can work these scenarios without diminishing his authority is a credit to his great powers as an actor. Lurie was lucky to get him on board.

Correspondent: Did you have any of the actors study dog movement at all?

Correspondent: Did you have any of the actors study dog movement at all?

Vigalondo: When you’re writing a script, sometimes the script is put into a nightmare. Sometimes, it’s giving you some gift. And in this case, when I was writing Timecrimes, I found a monster inside the story. But the story itself gave me the monster. I needed someone with a hidden face, with a scissors on the hand. So I found out that the story was building a monster. A monster that had these classical resonances, as you are telling. So I feel so fortunate. Because when you have a monster in your movie, the movie gets better most of the time. Every movie with a monster is better than the same story without the monster. You can apply this to all the other — to every example. I don’t know. If Million Dollar Baby had a monster, it would be a better film.

Vigalondo: When you’re writing a script, sometimes the script is put into a nightmare. Sometimes, it’s giving you some gift. And in this case, when I was writing Timecrimes, I found a monster inside the story. But the story itself gave me the monster. I needed someone with a hidden face, with a scissors on the hand. So I found out that the story was building a monster. A monster that had these classical resonances, as you are telling. So I feel so fortunate. Because when you have a monster in your movie, the movie gets better most of the time. Every movie with a monster is better than the same story without the monster. You can apply this to all the other — to every example. I don’t know. If Million Dollar Baby had a monster, it would be a better film.