This morning, the Federal Trade Commission announced that its Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials would be revised in relation to bloggers. The new guidelines (PDF) specified that bloggers making any representation of a product must disclose the material connections they (the presumed endorsers) share with the advertisers. What this means is that, under the new guidelines, a blogger’s positive review of a product may qualify as an “endorsement” and that keeping a product after a review may qualify as “compensation.”

These guidelines, which will be effective as of December 1, 2009, require all bloggers to disclose any tangible connections. But as someone who reviews books for both print and online, I was struck by the inherent double standard. And I wasn’t the only one. As Michael Cader remarked in this morning’s Publishers Marketplace:

The main point of essence for book publishers (and book bloggers) is the determination that “bloggers may be subject to different disclosure requirements than reviewers in traditional media.” They state that “if a blogger’s statement on his personal blog or elsewhere (e.g., the site of an online retailer of electronic products) qualifies as an ‘endorsement,'” due to either a relationship with the “advertiser” or the receipt of free merchandise in the seeking of a review, that connection must be disclosed.

In an attempt to better understand the what and the why of the FTC’s position, I contacted Richard Cleland of the Bureau of Consumer Protection by telephone, who was kind enough to devote thirty minutes of his time in a civil but heated conversation. (At one point, when I tried to get him to explicate further on the double standard, he declared, “You’re obviously astute enough to understand what I mean.”)

In an attempt to better understand the what and the why of the FTC’s position, I contacted Richard Cleland of the Bureau of Consumer Protection by telephone, who was kind enough to devote thirty minutes of his time in a civil but heated conversation. (At one point, when I tried to get him to explicate further on the double standard, he declared, “You’re obviously astute enough to understand what I mean.”)

Cleland informed me that the FTC’s main criteria is the degree of relationship between the advertiser and the blogger.

“The primary situation is where there’s a link to the sponsoring seller and the blogger,” said Cleland. And if a blogger repeatedly reviewed similar products (say, books or smartphones), then the FTC would raise an eyebrow if the blogger either held onto the product or there was any link to an advertisement.

What was the best way to dispense with products (including books)?

“You can return it,” said Cleland. “You review it and return it. I’m not sure that type of situation would be compensation.”

If, however, you held onto the unit, then Cleland insisted that it could serve as “compensation.” You could after all sell the product on the streets.

But what about a situation like a film blogger going to a press screening? Or a theater blogger seeing a preview? After all, the blogger doesn’t actually hold onto a material good.

“The movie is not retainable,” answered Cleland. “Obviously it’s of some value. But I guess that my only answer is the extent that it is viewed as compensation as an individual who got to see a movie.”

But what’s the difference between an individual employed at a newspaper assigned to cover a beat and an individual blogger covering a beat of her own volition?

“We are distinguishing between who receives the compensation and who does the review,” said Cleland. “In the case where the newspaper receives the book and it allows the reviewer to review it, it’s still the property of the newspaper. Most of the newspapers have very strict rules about that and on what happens to those products.”

In the case of books, Cleland saw no problem with a blogger receiving a book, provided there wasn’t a linked advertisement to buy the book and that the blogger did not keep the book after he had finished reviewing it. Keeping the book would, from Cleland’s standpoint, count as “compensation” and require a disclosure.

But couldn’t the same thing be said of a newspaper critic?

Cleland insisted that when a publisher sends a book to a blogger, there is the expectation of a good review. I informed him that this was not always the case and observed that some bloggers often receive 20 to 50 books a week. In such cases, the publisher hopes for a review, good or bad. Cleland didn’t see it that way.

“If a blogger received enough books,” said Cleland, “he could open up a used bookstore.”

Cleland said that a disclosure was necessary when it came to an individual blogger, particularly one who is laboring for free. A paid reviewer was in the clear because money was transferred from an institution to the reviewer, and the reviewer was obligated to dispense with the product. I wondered if Cleland was aware of how many paid reviewers held onto their swag.

“I expect that when I read my local newspaper, I may expect that the reviewer got paid,” said Cleland. “His job is to be paid to do reviews. Your economic model is the advertising on the side.”

From Cleland’s standpoint, because the reviewer is an individual, the product becomes “compensation.”

“If there’s an expectation that you’re going to write a positive review,” said Cleland, “then there should be a disclosure.”

But why shouldn’t a newspaper have to disclose about the many free books that it receives? According to Cleland, it was because a newspaper, as an institution, retains the ownership of a book. The newspaper then decides to assign the book to somebody on staff and therefore maintains the “ownership” of the book until the reviewer dispenses with it.

I presented many hypothetical scenarios in an effort to determine where Cleland stood. He didn’t see any particular problem with a book review appearing on a blog, but only if there wasn’t a corresponding Amazon Affiliates link or an advertisement for the book.

In cases where a publisher is advertising one book and the blogger is reviewing another book by the same publisher, Cleland replied, “I don’t know. I would reserve judgment on that. My initial reaction to it is that it doesn’t seem like a relationship.”

Wasn’t there a significant difference between a publisher sending a book for review and a publisher sending a book with a $50 check attached to it? Not according to Cleland. A book falls under “compensation” if it comes associated with an Amazon link or there is an advertisement for the book, or if the reviewer holds onto the book.

“You simply don’t agree, which is your right,” responded Cleland.

Disagreement was one thing. But if I failed to disclose, would I be fined by the FTC? Not exactly.

Cleland did concede that the FTC was still in the process of working out the kinks as it began to implement the guidelines.

“These are very complex situations that are going to have to looked at on a case-by-case basis to determine whether or not there is a sufficient nexus, a sufficient compensation between the seller and the blogger, and so what we have done is to provide some guidance in this area. And some examples in this area where there’s an endorsement.”

Cleland elaborated: “I think that as we get more specific examples, ultimately we hope to put out some business guidance on specific examples. From an enforcement standpoint, there are hundreds of thousands of bloggers. Our goal is to the extent that we can educate on these issues. Looking at individual bloggers is not going to be an effective enforcement model.”

Cleland indicated that he would be looking primarily at the advertisers to determine how the relationships exist.

[UPDATE: One unanswered concern that has emerged in the reactions to this interview is the degree of disclosure that the FTC would require with these guidelines. Would the FTC be happy with a blanket policy or would it require a separate disclosure for each individual post? I must stress again that Cleland informed me that enforcement wouldn’t make sense if individual bloggers were targeted. The FTC intends to direct its energies to advertisers. Nevertheless, I’ve emailed Cleland to determine precisely where he stands on disclosure. And when I hear back from him, I will update this post accordingly.]

[UPDATE 2: Cleland hasn’t returned my email. But his response in this article in relation to Twitter (“There are ways to abbreviate a disclosure that fit within 140 characters”) suggest that bloggers will be required to disclose per post/tweet.]

[UPDATE 3: A commenter has suggested: Why not return or forward all the review copies that you receive directly to Mr. Cleland?]

[UPDATE 4: In an October 8, 2009 interview with Fast Company, Cleland has backpedaled somewhat, claiming that the $11,000 fine is not true and indicating that the FTC will be “focusing on the advertisers.” The problem is that page 61 of the proposed guidelines clearly states, “Endorsers also may be liable for statements made in the course of their endorsements.” And endorsers, as we have established in this interview, include bloggers. However, Cleland is right to point out that the guidelines do not point to a specific liability figure and that it would take a blogger openly defying a Cease & Desist Order to enact penalties. The Associated Press was the first to report the $11,000 fine per violation. Did somebody at the AP misreport the penalty information? Or was it misinterpreted?

Some investigation into FTC precedents would suggest that the AP reported these concerns correctly. Here are some precedents for the up to $11,000 fine per violation: non-compliance of wedding gown label disclosure, non-compliance of contact lens sellers, and an update to the federal register. On Monday, the FTC precedents establish heavy penalties for non-compliance, the the guidelines themselves specify penalties as endorsers, and Cleland insists that bloggers who review products are “endorsers.” On Wednesday, Cleland now claims that bloggers won’t be hit by penalties. The FTC needs to be extremely specific about this on paper, if it expects to allay these concerns. (Thanks to Sarah Weinman for reporting assistance on this update.)]

Correspondent: Ajaydev Naliur said to you that the most difficult part of integrating into the larger white community was “not being able to socialize with them like we do with the Indian families. The people at work never say, ‘A.J., come to my house for dinner, come to my home.'” Now if Naliur has only a professional relationship with the Americans and he fears bringing Indian food even to the Walmart food day potlucks, then surely there’s a multiculturalism problem here. And I’m curious about why there’s this lack of integration.

Correspondent: Ajaydev Naliur said to you that the most difficult part of integrating into the larger white community was “not being able to socialize with them like we do with the Indian families. The people at work never say, ‘A.J., come to my house for dinner, come to my home.'” Now if Naliur has only a professional relationship with the Americans and he fears bringing Indian food even to the Walmart food day potlucks, then surely there’s a multiculturalism problem here. And I’m curious about why there’s this lack of integration.

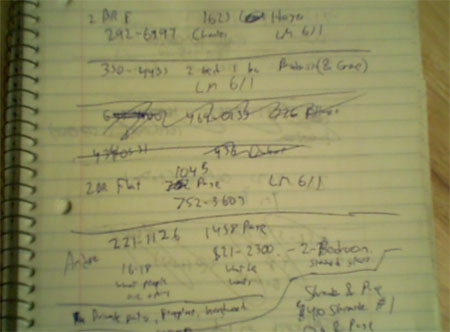

The result of all this scribbling has involved quite a few notebooks, most of which I have kept in two file drawers. I’ve just pulled one out at random and I see a drawing of a floor plan for a San Francisco streetcar. Flipping the pages, I see lists of interesting words I’ve noted in novels, such as “contrapposto” and “ephemeron.” There’s an awkward poem that begins with the line “Pigeon pecking pieces from discarded pizza boxes / Whopper wrappers flayed upon a health nut in detox.” I see a hasty budget I’ve drafted for a film shoot, noting the costs of renting fresnels, Tota kits, flex-fills, and C stands. Another page offers this curious list:

The result of all this scribbling has involved quite a few notebooks, most of which I have kept in two file drawers. I’ve just pulled one out at random and I see a drawing of a floor plan for a San Francisco streetcar. Flipping the pages, I see lists of interesting words I’ve noted in novels, such as “contrapposto” and “ephemeron.” There’s an awkward poem that begins with the line “Pigeon pecking pieces from discarded pizza boxes / Whopper wrappers flayed upon a health nut in detox.” I see a hasty budget I’ve drafted for a film shoot, noting the costs of renting fresnels, Tota kits, flex-fills, and C stands. Another page offers this curious list: