[Stewart O’Nan has also appeared twice on The Bat Segundo Show: Show #161 (2007, 38 minutes) and Show #454 (2012: 57 minutes).]

Stewart O’Nan has been called “a national treasure” by Three Guys One Book. The Cleveland Plain-Dealer has compared him to Dickens. In The New York Times, Joanna Smith-Rakoff suggested that O’Nan was influenced by “the spectre of Henry James.”

O’Nan’s twelfth novel, Emily, Alone — a sequel to O’Nan”s 2002 novel, Wish You Were Here that doesn’t require that you read the first book — follows an 80-year-old woman as she carries on a quiet routine in her Pittsburgh home. Her husband is dead. Her children have grown up and moved away. Her once lively dog Rufus is, quite literally, on his last legs. Her friend Arlene could go any minute. Despite this mortality, the novel remains determined to capture Emily’s life through very careful sentences devoted to telling details. When Emily replaces a box of Kleenex, we get economical insight into how she spends her money (“She’d bought a three-pack last week, saving a dollar, as always, with a coupon.”). We learn of generational differences when Emily considers her daughter Margaret’s attitude (“Thank-you notes belonged to the same category of useless formalities her square parents followed blindly, like sitting down to meals at prescribed times or going to church on Sunday.”). When an older acquaintance dies, O’Nan foreshadows the insufficient shorthand Emily is likely to have directed towards her in a few years (“She always had a lot of energy”).

I had interviewed Stewart O’Nan before in 2007 for The Bat Segundo Show. And after reading Emily, Alone, I had hoped to set up a second interview. Unfortunately, O’Nan’s hectic schedule of teaching and long driving to author events made things a bit difficult. And when I received an unexpected jury duty summons in the mail, I prepared for the distinct possibility that a few weeks of my life would be sacrificed to the courtroom.

We started volleying by email. And the two of us learned that we both had quite a lot to say about American fiction. Our conversation touched upon the influence of Richard Yates, what a writer can learn from John Gardner, avoiding parody and creating dimensional characters, and how one can protest marketplace realities while appealing to the reader. My many thanks to Stewart for taking time out of his busy schedule to answer my somewhat verbose concatenations.

* * *

Reluctant Habits: Before we started this conversation, I remarked upon a jury duty summons that I had received (and should our conversation extend into a diversion from the courtroom, thank you very much in advance!). This led us both to remark upon the importance of civil duty in American life. But this got me thinking. Emily Maxwell is someone who maintains her dignity, a quality that might also be described as a civil duty. And your work offers an attention to the everyday that, when stacked against other fiction, might almost be said to originate from a similar impulse — namely, a civil duty to portray certain everyday Americans who don’t always get these narratives. To what extent do you feel that it’s your civil duty to portray families like the Maxwells? Does the duty ever burden you or threaten to take away from the curiosity or the fun? Additionally, why do you think civil duty has been given short shrift in recent American fiction? To what degree are you aware that you’re working a corner of the room that few other writers wish to peer into?

Stewart O’Nan: Emily does see herself as a part of larger social constructs–her marriage, her family (as a mother), her original family (as a daughter), her church, her neighborhood, the city of Pittsburgh, the town of Kersey, the old-guard Republican party–yet for all her sense of civic duty, she’s incredibly private and not always available, emotionally or otherwise. Plus so much of her world is gone and lives only in her memory. So she’s not as involved in that larger life as she sometimes wishes she were. Some days the only soul she speaks to is her dog, Rufus.

I think when I run into a character I find interesting, I feel a wild curiosity about him or her. How does this person feel, and how does he or she get through the days? What’s important to this person? Usually I write about people unlike myself, so there’s a constant process of discovery, of trying to get close enough and understand enough so I can provide the reader with a true sense of intimacy. And definitely, when I’m taking on someone in a realistic mode, I feel a responsibility to the character, in how I portray him or her. Not that I’ll soft-sell Emily’s faults (readers will want to shake her at times) or make things easy on her, even though I care for her deeply. The goal is to be honest and go deep, find the voice and style and structure to bring across her emotional life as powerfully as possible (not as loudly as possible, or as showily as possible, or as cleverly as possible), with the hope that readers will see their own lives and their own Emilys and add their memories and emotions to the book and end up being moved, not in a corny way, but really moved.

Impossible, I know, but that’s what interests me: How does it feel to be you? When I discover a character like Emily, or Manny in Last Night at the Lobster, or Patty in The Good Wife, after following them a while I realize that their stories are huge stories, their lives shared by millions of people yet rarely examined or taken seriously. So it’s an opportunity to take the reader a place they might never go otherwise and show them a whole world that’s been right in front of them the whole time, hidden in plain sight.

I’m aware that during the whole time I’ve been publishing, the main stage of American literary fiction has featured a kind of pyrotechnic fabulism. The Ice Storm is ’93, I think, The Virgin Suicides right around there, Infinite Jest is ’95, Lethem’s putting out his genre-bending stuff around then…and I dig all that stuff. I cut my teeth on Gaddis and Gardner and Gass and Barthelme and Barth and Coover and Hawkes too, and I admire the comic virtuosity of all these writers, first- and second-generation. The Speed Queen is obviously a whacky metafiction, and A Prayer for the Dying is a bit of a bravura performance in the manner of Charles Johnson, just as The Night Country owes much of its soul to Ray Bradbury and George A. Romero, so I haven’t entirely forsaken those roots, but even in those books I hope I’m using those dire means because they seemed to me the best solution — the unique solution, the ex-engineer would say — to the problem off getting my characters’ worlds across to the reader as powerfully as possible. Because in the end the writing isn’t what’s important — it’s just a medium. If the reader pays more attention to the writing than to what’s going on with the characters, the writing isn’t working.

RH: In your essay, “The Lost World of Richard Yates,” you observed that “the danger Yates courts is combining the conflicted character with the average or unexceptional person — with a talent I can only aspire to.” Yates, rather famously, was influenced by F. Scott Fitzgerald — which is quite interesting, seeing as how Fitzgerald often wrote about the rich and Yates gravitated toward the middle class. Following this natural path of inspiration, we see in your work that the danger you’re courting involves both the working class and the middle class. Last Night at the Lobster very clearly documents working class life. But I’m wondering to what degree the 2008 election — seen in Emily, Alone — served as an effort to chronicle a social sector that is rapidly eroding. In other words, as was suggested in the recent PEN America correspondence between David Gates and Jonathan Lethem, are you setting yourself up to be more of a historical novelist rather than a social novelist? What do you think accounts for the downmarket class drifting in this trajectory from Fitzgerald to Yates to you? How does this constant process of discovery pretty much demolish literary influence (whether Yates or pyrotechnic fabulism)?

O’Nan: Oh, definitely social fiction, utterly contemporary fiction, the skin of life as it’s lived now. Which is why the last seven books or so are set right here, right now, as opposed to the first five, which were all set in the historical past, in very different American eras and locales. How does life feel? What do we care about, what do we really fear? What do we really feel about the people closest to us, about ourselves? I still think fiction lets us go deeper into what life feels like than any other medium. Film is shallow, nonfiction is suspect (the more creative, the more suspect), memoir is unreliable and self-serving. The novel, by its very name, is utterly plastic, capable of taking any form, focusing on anything (an entire epoch or a guy riding an escalator after buying a pair of shoelaces — both accounts hilariously footnoted with unexpected yet absolutely true musings). Realism is a misnomer, since any art takes on, twists, or knowingly overthrows a convention to get the feel of life across to the reader/viewer/listener. Shields in Reality Hunger says he’s against the novel, then lists a whole raft of anti-novels that he claims are exceptions. But the anti-novel is still a novel. So it’s like saying, I don’t like vegetables, but I do like beets and carrots and squash and peas and kohlrabi and…While it’s true that viewers love reality TV, there’s a formulaic sameness to even the best reality shows that can’t approach the variety, depth, drama and comedy of scripted shows, the best of which — Deadwood, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Party Down — make reality TV look shallow and silly. Likewise, documentary film, feature journalism since the mid-’60s, and everyday newspaper writing since the ’80s, have taken on as many of fiction’s tools as they can to seduce a larger audience. What’s the basis of all mass communication? Tell a good story.

Fitzgerald and Yates had their specific social territory which they rarely strayed from, especially Yates, who, though he wrote from the ’40s till the ’90s, only once stepped away from his home base of the ’40s and ’50s in Disturbing the Peace. I haven’t claimed one territory, and wouldn’t want to. I’m no spokesperson or poster child. As a reader I have very catholic tastes (Stephen King and Virginia Woolf, Ray Bradbury and John Wideman). So it makes sense that as a writer I write very different books about very different things. It’s been that way from the start, and because I don’t have to fulfill any expectations, I’m free to write about the affluent, the middle class, the working class, the poor, children, teenagers, young adults, the middle-aged, the elderly, urban life, the suburbs, small towns, country, frontier, and in any manner I choose. I’m not locked into a bankable voice or style, so it doesn’t become self-parody or shtick, like James Taylor singing Christmas carols with the same intonation he’d sing Motown covers. If there’s a common thread, I’d say I tend to dip into very American subcultures and address very American questions or traits. In each book there are influences, most of them consciously chosen — say, James Salter in A World Away, the Cormac McCarthy of Blood Meridian and George A. Romero in A Prayer for the Dying, or Sherwood Anderson and Dickens in Last Night at the Lobster — never in imitation but using their schemes to support whatever I’m doing. Hoping it turns out to be interesting, well done and ultimately true. And if it doesn’t, well, hell, they’re not all going to be good. It’s not supposed to be easy. If you’re a writer, you keep trying. You don’t throw your hands up and say the novel is dead just because yours is.

RH: I bring up the idea of Emily, Alone being historical (both in terms of literary influence and charting a specific time), rather than “utterly contemporary” (as you suggest), because there’s a chapter late in the book (“The Lesser of Two Evils”) where we understand that, despite Emily being a “lifelong Republican,” her life choices involve that sense of duty we were discussing here at the outset. She asks the question, “Was it too much to ask for someone she could believe in?” Yet she leaves the gym with the I VOTE TODAY sticker on her lapel, feeling a sense of pride. Here is someone who feels compelled to be part of the community, but who also finds some solace in being solitary. My takeaway here is that Emily, who has bought a brand new car (and if she didn’t have the money, this deal may have been comparable to some dubious tranche loan) and who is also contending with the home in her neighborhood that’s about to be sold. You’re telling me, Stewart, that this materialist solace competing with the communal solace (whether it be Arlene, Rufus, or even the reluctant relatives who come visit) isn’t capturing a national mood (or a specific type of older person in 2008) to some degree? Doesn’t the process of keeping a novel alive — especially social fiction — involve rigorous interplay between well-defined characters and where they are likely to stand in their particular period? What makes the process of knowing people in 2011, in 2008, or the Civil War different on a novel-to-novel basis? Is this simply a matter of how much you’re willing to throw yourself into a time period or talk with people or think about these motivations?

O’Nan: When I say contemporary, I mean that I was writing the novel at the very same time as the events (and the world, the moment) it describes. So that, unlike when you’re writing a historical novel, the zeitgeist hasn’t been codified. You have the opportunity to feel it and get it across fresh through your character. Emily is so much of the past that she’s actually a little behind the times, and the book, at heart, is about the collision of her rich and busy memories with the empty and quiet present. I didn’t write her story to capture the national mood, but in her brushes with the world, some of it might bleed through. Her story is essentially personal and private, unlike, say, Patty’s or Manny’s or the Larsens, all of whom have to confront the current world in a very public way, often against their will. But in all of these cases, it’s a question of what, from the larger world, realistically and naturally, would impinge on their lives. It’s their motivations and their world that everything has to come out of, and that comes from staying close to them, knowing them intimately and trying to see the world–their private world and the larger world–through their eyes, not impressing my views onto them and the world. It’s their book, not mine.

And it also differs book to book in how important the time frame is to the storyline. Emily’s storyline is anchored in 2007-2008, but it could have happened in other years and felt relatively the same, whereas A World Away, set in 1943, is so tied to larger world events, and the characters so tied to the movements of the outside world that it naturally contains more of the zeitgeist, for lack of a better word.

It’s a tough question, especially for this particular novel, because while it’s trying to take on some very large areas — time, family, memory, life, death — it’s trying to do so quietly, almost sneakily.

RH: This discussion about fiction having resonant points with American life brings us to inevitable comparisons between Emily, Alone and its prequel, Wish You Were Here. The first book, which is quite sprawling, seems determined to capture almost every detail, from the book barn to the specific movies that the Maxwells watch to discussions of the board game Sorry. There’s also the subplot involving the missing person at the gas station, which threatens to take away from such character dilemmas as Margaret’s recovery from alcoholism, Kenneth hiding his vocational problems, and so forth. By contrast, in Emily, Alone, there’s something of a concession to narrative right from the get-go with that incident at the buffet. What ultimately accounts for Emily, Alone‘s leaner feel? Do you feel that there was any loss of control when you wrote Wish You Were Here? That the previous book involved creative propagation you had to go the distance with? Aside from keeping the focus on Emily, what steps did you take in curtailing the possibility of writing another 600 page novel? Were there certain advantages in thinking about the Maxwell family before that allowed you to rein things in? How does some of this account for the quieter and sneakier investigation into larger areas? (And while we’re on the subject, do you see the Maxwells as your answer to Rabbit Angstrom or Frank Bascombe?)

O’Nan; Wish purposely slows things down and doesn’t make the usual pregnant narrative promises to the reader we expect from fiction. I was trying on a new mode of storytelling, trusting John Gardner’s dictum that if a character is worthy of and capable of love, then the reader will follow him or her anywhere. I expected that 80% of the readers who opened the book would never finish it, and that was fine with me. That was the risk I was willing to take for the reward of getting deep into the characters and their worlds, thinking that the readers who did stick with it would mingle their own lives and memories with those of the Maxwells and come away with a richer, more intimate experience than from some plug-and-chug potboiler of a story line. Even the girl who goes missing line takes place off-stage and is really just K’s version of avoidance and escape (they all have some version of escape from what’s supposed to be family togetherness). The novel’s put together by poetic juxtaposition, by tone, by mood, and the fact that it’s so long (and was a hundred-plus pages longer in ms) just emphasizes that strategy. No nifty ironies, no self-conscious tricks, no mannered quirkiness to distract the reader. It lives or dies by the quality of its observations, by its truth (or lack thereof). As a friend of mine says, it’s an epic about nothing. My wife calls it the Big Boring Book. And that’s fine. Everyone doesn’t have to like every book. (And honestly, every book isn’t going to be good.) But the people who do get into the book really feel like they’re part of it. Some say it’s spooky — it’s as if I’ve been eavesdropping on their families, or reading their minds — so I feel like the method worked. Not for everyone, but for more than the 20% I’d hoped for.

And it’s a book that couldn’t have been written by anyone else, which makes me happy. I guess it was a bit of a protest. A quiet maybe even underground protest (since no one really cares), but a definite break from what I’d been doing previously, and what you’d call the norm. Ditching the whole here-we-are-now-entertain-us premise. A book wholly on the writer’s terms.

Emily, Alone is organized a little differently, around what puzzles or bothers or thrills her — the bumps in her otherwise quiet days — but also makes no promises to the reader plotwise, other than that she cares and worries about the people closest to her, and of course Rufus. And at their age, she has reason to worry.

In Wish, I was coming to know all the different Maxwells at that one moment, a turning point in their family life. Going into Emily, Alone, I knew Emily well, but I knew I wanted to get deeper and closer, really find out how she became the person she was in Wish and the person she is now, seven years later. What’s changed? What could possibly be new? A lot, it turned out, though I didn’t know exactly what when I sat down to write it.

The scope of Emily, Alone is narrower but deeper, necessarily, by my choice of point of view, and that’s what I was hoping for — a book even quieter and more intimate than Wish, a book comprised of flurries of busyness and then long stretches of stillness. Another book only I could write, and one some readers would see their lives in, and the lives of their sisters and aunts and mothers and grandmothers, I hope.

RH: So it seems to me that readers are very much an important factor when you’re writing a book. On the other hand, as Ron Charles recently suggested, your determination to chart the seemingly routine results in “the Kobayashi Maru scenario of book marketing.” Yet here’s the double-edged sword. If you’re hoping to write books where readers see their lives, or the lives of someone dear to them, then one might conclude that Emily, Alone isn’t wholly on the writer’s terms. Have you had to give more to the readers with the more recent books? If Emily, Alone is more of a Rorschach test for readers, then how do you find ways of protesting? If protesting is part of your voice, don’t you have to do that? Or are you happy with the present compromise?

O’Nan: The Rorschach blot is the protest, that’s the beauty of it. In Wish and Emily (and to a lesser extent in The Good Wife and Last Night at the Lobster), I’ve asked the reader to make the sacrifices, giving up any semblance of the usual set-up/build-up/payoff of conventional storytelling without substituting the overactive surface or off-beat/trendy characters of the contemporary literary scene. Instead of the industry standard extraordinary character in an ordinary situation or the ordinary character in an extraordinary situation, I’m going — like Yates — for that rare, dull bird, the ordinary character in an ordinary situation. As Gardner says, as readers we naturally hold any fiction up to life, testing it for truth, and since that rare, dull bird is most of us, I actually have a better chance of connecting deeply. In these books, if I’ve done them well enough, readers will also hold their lives up to the fiction, completing the exchange. Everyone has an Emily.

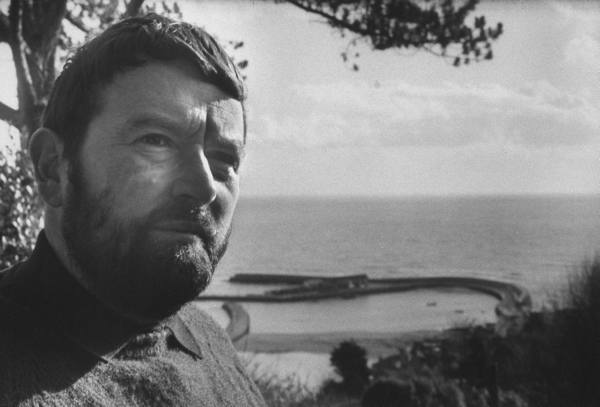

(Image: Sidney Davis)

Over the course of several interviews, John Fowles enjoyed recycling one particular anecdote concerning The Magus. The then bigshot author once received a letter from a woman who didn’t care for his book. The woman asked Fowles if two of the novel’s characters got together at the end. Fowles wrote back and said, “No.” He received another letter from a New York attorney dying of cancer in a hospital. The lawyer asked the same question, but, unlike the woman, informed Fowles that he enjoyed the book. Fowles replied, “Yes.” In 1986, Fowles would tell a dull interviewer seeking literal-minded answers, “I tell that story because that’s how I feel — I don’t know the answer. And I tend to react as people want, or don’t want it — if they’ve annoyed me — to end.” But Fowles’s story after the story does have me wondering about the novelist’s responsibility. If a novelist leaves his volume open-ended, does he not have some duty to know every aspect of his characters as he knows the back of his hand? On the other hand, if Fowles led his narcissistic schoolteacher Nicholas Urfe to a specific point, perhaps he’s off the hook for anything beyond these final words:

Over the course of several interviews, John Fowles enjoyed recycling one particular anecdote concerning The Magus. The then bigshot author once received a letter from a woman who didn’t care for his book. The woman asked Fowles if two of the novel’s characters got together at the end. Fowles wrote back and said, “No.” He received another letter from a New York attorney dying of cancer in a hospital. The lawyer asked the same question, but, unlike the woman, informed Fowles that he enjoyed the book. Fowles replied, “Yes.” In 1986, Fowles would tell a dull interviewer seeking literal-minded answers, “I tell that story because that’s how I feel — I don’t know the answer. And I tend to react as people want, or don’t want it — if they’ve annoyed me — to end.” But Fowles’s story after the story does have me wondering about the novelist’s responsibility. If a novelist leaves his volume open-ended, does he not have some duty to know every aspect of his characters as he knows the back of his hand? On the other hand, if Fowles led his narcissistic schoolteacher Nicholas Urfe to a specific point, perhaps he’s off the hook for anything beyond these final words:

In Geoff Dyer’s Otherwise Known as the Human Condition, there’s an essay in which Dyer describes his reading habits. He writes about a late stage wade into Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. “I could make neither head nor tail of the first part,” notes Dyer. “[B]ut, since the book was short and the end in sight almost from the first page, I finished it and realized that it was indeed the masterpiece everyone had claimed.” It’s safe to say that this knowingly superficial take, coming from a man

In Geoff Dyer’s Otherwise Known as the Human Condition, there’s an essay in which Dyer describes his reading habits. He writes about a late stage wade into Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. “I could make neither head nor tail of the first part,” notes Dyer. “[B]ut, since the book was short and the end in sight almost from the first page, I finished it and realized that it was indeed the masterpiece everyone had claimed.” It’s safe to say that this knowingly superficial take, coming from a man

The above sentiment comes from Annandine, a character in a manuscript entitled The Silencer, modeled upon some philosophical chatter between a frustrated translator named Jake Donoghue and an industrialist/sophist named Hugo Belfounder, which is contained within Iris Murdoch’s debut novel, Under the Net. And if all that makes the book sound like a matryoshka doll with endless porcelain layers that need to be opened if the reader has any hope of unraveling the truth (to some degree, it is), then I should also note that Under the Net is also a sprightly picaresque novel. There are dogs, fireworks, giant Roman film sets occupied by socialists, martinets working at hospitals, experimental theatrical performances, and mad searches for people in pubs.

The above sentiment comes from Annandine, a character in a manuscript entitled The Silencer, modeled upon some philosophical chatter between a frustrated translator named Jake Donoghue and an industrialist/sophist named Hugo Belfounder, which is contained within Iris Murdoch’s debut novel, Under the Net. And if all that makes the book sound like a matryoshka doll with endless porcelain layers that need to be opened if the reader has any hope of unraveling the truth (to some degree, it is), then I should also note that Under the Net is also a sprightly picaresque novel. There are dogs, fireworks, giant Roman film sets occupied by socialists, martinets working at hospitals, experimental theatrical performances, and mad searches for people in pubs.

Correspondent: In the introduction for The Collected Stories, which has been collected all in one book and published just in time for your birthday, you allude to there being five different phases of your writing life. What was interesting to me was that you mentioned the fourth phase, which was just after your husband had passed away, and you say that you were writing stories and these Western novels because you wanted to have a family. Your kids had gone away and all that. I was curious why the family on page meant more or needed to be there in addition to the real people in your life.

Correspondent: In the introduction for The Collected Stories, which has been collected all in one book and published just in time for your birthday, you allude to there being five different phases of your writing life. What was interesting to me was that you mentioned the fourth phase, which was just after your husband had passed away, and you say that you were writing stories and these Western novels because you wanted to have a family. Your kids had gone away and all that. I was curious why the family on page meant more or needed to be there in addition to the real people in your life.  Correspondent: I wanted to first of all start with the notion of Harlem as an area. There are numerous skirmishes throughout history, some of them based off of racist fears about what Harlem’s boundaries are. And even when you were in Texas, you describe in this book creating an imaginary map of Manhattan. So given this, and given the fact that one person will call Harlem “a ruin,” another person will call it “an East Berlin whose wall is 110th Street,” how can any one person describe its totality? I mean, can this book or can any book really capture it? Or do you essentially fall into the

Correspondent: I wanted to first of all start with the notion of Harlem as an area. There are numerous skirmishes throughout history, some of them based off of racist fears about what Harlem’s boundaries are. And even when you were in Texas, you describe in this book creating an imaginary map of Manhattan. So given this, and given the fact that one person will call Harlem “a ruin,” another person will call it “an East Berlin whose wall is 110th Street,” how can any one person describe its totality? I mean, can this book or can any book really capture it? Or do you essentially fall into the

In Alexandra Styron’s forthcoming book, Reading My Father, she describes liberating a galley of Sophie’s Choice, a presale unit freshly arrived at the family home, at the age of twelve. It was the spring of 1979. Her plan was to read the mint green paperback between classes. She felt it incumbent “to somehow validate the rumors of his greatness.” Young Alexandra discovers that the novel bores the tears out of her. “The difficult vocabulary and historical references kept eluding me,” she writes, “until finally I began to let them sail by, unchallenged.” Further, upon encountering her father’s libidinous passages, she then becomes embarrassed, wincing “at the liberal sprinkling of words like fucking and horny and lust.” (Here’s the full tally according to Amazon’s Look Inside! feature: “fucking” — 29 counts; “horny” — 4 counts; and “lust” — 20 counts. I am also informed that readers in need of steady doses of the mildly profane are likely to find a good deal more “fuck” and “fucking” in Philip Roth’s Zuckerman books. Miles Davis’s autobiography, published a decade after Sophie’s Choice, contains 672 uses of the word “fuck.” I think it’s safe to say that Styron was pushing the “fucking” boundaries no more and no less than any other writer around the time. Perhaps his striking tone says something about his ability to alarm.)

In Alexandra Styron’s forthcoming book, Reading My Father, she describes liberating a galley of Sophie’s Choice, a presale unit freshly arrived at the family home, at the age of twelve. It was the spring of 1979. Her plan was to read the mint green paperback between classes. She felt it incumbent “to somehow validate the rumors of his greatness.” Young Alexandra discovers that the novel bores the tears out of her. “The difficult vocabulary and historical references kept eluding me,” she writes, “until finally I began to let them sail by, unchallenged.” Further, upon encountering her father’s libidinous passages, she then becomes embarrassed, wincing “at the liberal sprinkling of words like fucking and horny and lust.” (Here’s the full tally according to Amazon’s Look Inside! feature: “fucking” — 29 counts; “horny” — 4 counts; and “lust” — 20 counts. I am also informed that readers in need of steady doses of the mildly profane are likely to find a good deal more “fuck” and “fucking” in Philip Roth’s Zuckerman books. Miles Davis’s autobiography, published a decade after Sophie’s Choice, contains 672 uses of the word “fuck.” I think it’s safe to say that Styron was pushing the “fucking” boundaries no more and no less than any other writer around the time. Perhaps his striking tone says something about his ability to alarm.)