On June 8, 2011, I met Susan Freinkel, author of Plastic: A Toxic Love Story, at a Park Slope cafe. The intent was to record a conversation for The Bat Segundo Show. Unfortunately (and I blame the heat for my negligence here; I also had this funny idea of walking three miles to the cafe and three miles back home in very humid weather), some setting on the recorder was accidentally flipped to the internal microphone early into the conversation, resulting in muddled audio that was entirely unsuitable for listeners. In an effort to salvage this very interesting conversation, which deals with the impact of plastic on our environment, I have transcribed the entire 8,000 word talk.

Correspondent: Okay, so I am here with Susan Frienkel, who is the author of the charming volume, Plastic: A Toxic Love Story. Susan, how are you doing?

Freinkel: I’m doing great. I’m happy to be here.

Correspondent: I’m happy to talk love and toxicity.

Freinkel: (laughs)

Correspondent: This book started off with your own personal effort not to touch plastic. But even Beth Terry, one of the people foregoing plastic who you interview near the end of the book, says that she finds herself still using credit cards. Because she says that plastic lasts a long time. I’m wondering. Will reducing disposable plastic — of which we both have disposable plastic here, these cups [motioning to plastic cups containing cold beverages in 90 degree heat], it’s really terrible — will this alone do the trick? I mean, one can make the argument that the plastic which comes with the ATM and the credit cards that we replace every couple of years or the latest smartphone you have to upgrade and all this — this is just as much of a waste as a disposable lighter. So might this also contribute to the problem?

Correspondent: This book started off with your own personal effort not to touch plastic. But even Beth Terry, one of the people foregoing plastic who you interview near the end of the book, says that she finds herself still using credit cards. Because she says that plastic lasts a long time. I’m wondering. Will reducing disposable plastic — of which we both have disposable plastic here, these cups [motioning to plastic cups containing cold beverages in 90 degree heat], it’s really terrible — will this alone do the trick? I mean, one can make the argument that the plastic which comes with the ATM and the credit cards that we replace every couple of years or the latest smartphone you have to upgrade and all this — this is just as much of a waste as a disposable lighter. So might this also contribute to the problem?

Freinkel: Well, I think half of all plastic goes to single use plastics. So that’s a lot of plastic. And that’s a lot of plastic that gets wasted. It’s a poor use of resources. But I also think it’s emblematic of this whole lifestyle in which we assume that we need a new cellphone every eighteen months. If we’re lucky. Or we assume that we need a new computer every two years. We have to wipe out our wardrobe and get whole new clothes. So I think there’s a whole lifestyle that plastic facilitates in this emblematic. Will it do the trick? I mean, that sort of depends upon what the trick is. If we want to live in more sustainable fashion, we’re going to have to learn how to get away from that throwaway mindset. Which is an incredibly modern thing.

Correspondent: Yes. But we’re talking about two throwaway mindsets. The throwaway of a single use plastic. And the lifestyle we live. Well, it’s inescapable. We’re locked into the smartphone multiyear contract. At the end, there’s something else. And if we actually want to keep up with the Joneses, so to speak, or even keep up with the latest software or the latest hardware, we’re at the behest of our own technology. Is there really a solution other than cut down on single use? Does that do the trick?

Freinkel: Well, again, it depends on what doing the trick means. If we stop using so many single use things like these lovely plastic cups and straws that we’re drinking from right now…

Correspondent: I’m filled with remorse.

Freinkel: (laughs) You know, that would reduce the amount of plastic that we make. And it would certainly reduce a lot of the plastic pollution that we are troubled by now. I think the reason that we’re having such a hard time grappling with the grocery bag issue, the reason there are these huge political fights around it, isn’t just that the plastic industry that is fighting those efforts to, say, ban bags. It’s also that we’re very ambivalent. We have developed a whole mindset that expects to be continually refreshing ourselves with new things in turn. And, yeah, you need a new smartphone. You want to stay up with the latest technology. But we also have a whole economy and a whole consumption orientation that presumes we need to do that. So I’m not really troubled by the use of plastic in durable goods. I love my computer. I love my cell phone. I don’t want to give those up. I don’t know if I need to replace them every two years. But I surely don’t need to do this. If I was really a good advocate for my book, I would have come with my own reusable cup.

Correspondent: (flourishing towards the plastic cups) I said, “She’s going to see me with this. And I’m going to be outed right here.” I’m thankful we’re both just as guilty here.

Correspondent: (flourishing towards the plastic cups) I said, “She’s going to see me with this. And I’m going to be outed right here.” I’m thankful we’re both just as guilty here.

Freinkel: I actually debated whether to bring a reusable cup with me. To bring it across the country. And I said, “God, I do not want to schlep that cup.” I did bring my reusable bag.

Correspondent: That’s good. Well, I have this backpack, which has received much usage. But I mean, to go back to this problem. Biodegradability. You point to credit cards in the book. The card market is very much being dictated by what the card issuers decide. It’s not necessarily NatureWorks — this effort to try and have biodegradable plastic. So if the free market or the private industry decides the course of everything, I mean, what recourse is there? Does it require austere government measures such as San Francisco banning plastic bags? What of this? It almost seems like you have to prohibit everybody in order to actually get them on the program.

Freinkel: Yeah, the free market right now — green stuff, sustainable stuff is a cool market niche. And so companies are responding. They’re creating biodegradable products. They’ve been creating products that don’t have toxic chemicals. Blah blah blah. But the free market is also this fickle enterprise. And it can decide, as you saw — I mean, the Times had a story a couple of weeks ago about how all these companies are retrenching on their clean household cleaning products. Because they cost more. And in this economy, people aren’t willing to shell out an extra dime to have something that’s more environmentally preferable. So I’m not advocating austere government measures to deal with it. I think that government is doing more to encourage research in those areas. And in some cases, like dealing with toxins and dealing with the chemicals that are in commerce, people who are concerned about that — I don’t think that if you’re concerned about those synthetic chemicals and the lack of our knowledge of what synthetic chemicals are in consumer products, I don’t think that’s something that consumers can shop their way out of. I think that we need government regulation on that. On the other hand, I think consumer interest in cleaner stuff has helped stimulate that.

Correspondent: Well, you do point, for example, to the plastax — a lexical blending I’m not particularly fond of, but we’ll use it for the purposes of this discussion. A tax on plastic bags in Ireland that has actually proven to be very successful in cutting down on plastic bags. I mentioned just in the previous question about San Francisco and its plastic bag ban. This has had great results. But what is the best result outside of outright bans and taxes on getting people to change their lifestyles, so to speak, on plastic bags or something else?

Freinkel: It sort of depends on what we’re talking about. So if we’re talking about something like plastic bags — single use plastics — I personally feel, I’m not big on the idea of bans. Because they really tick people off. And in San Francisco, the ban on the bag was just on plastic. It didn’t apply to paper bags. And consequentially, a lot of stores in San Francisco, and the stores — if they’re small stores, they’re still giving out plastic bags; if they’re the big chain stores, they’re giving out paper bags. And so people are still using single use bags. They’re not as resistant in the environment as the plastic. But they’re still paper. Part of the problem with single use stuff is that we get a lot of this stuff for free. And so we don’t actually have to think about the fact that they have costs. The cost is built into my ice coffee here. It probably costs a little bit extra because the store has to pay for these single use cups that they give out. And there’s environmental costs associated with these that you pay in your taxes, you pay in your garbage bills, and whatever. So I like the idea of using the market as a way to alert people to the fact that this stuff has a cost. And I also really believe that all of us are penny-pinchers. And if we’re forced to pay five or ten cents for a plastic bag, or pay an added premium to get it in a non-reusable cup, that’s going to make people think a little bit. It’s not going to drive them off the scene. And some people just want to completely get rid of them. But it does reduce them. In Ireland, that “plastax” — that twenty-five cent fee on plastic bags, that dropped the use of plastic bags by about 90% in its first few months. In Washington DC, where it’s just five cents on plastic bags, they’ve substantially reduced the plastic bags. And that’s money being collected to clean up the Anacostia River.

Freinkel: It sort of depends on what we’re talking about. So if we’re talking about something like plastic bags — single use plastics — I personally feel, I’m not big on the idea of bans. Because they really tick people off. And in San Francisco, the ban on the bag was just on plastic. It didn’t apply to paper bags. And consequentially, a lot of stores in San Francisco, and the stores — if they’re small stores, they’re still giving out plastic bags; if they’re the big chain stores, they’re giving out paper bags. And so people are still using single use bags. They’re not as resistant in the environment as the plastic. But they’re still paper. Part of the problem with single use stuff is that we get a lot of this stuff for free. And so we don’t actually have to think about the fact that they have costs. The cost is built into my ice coffee here. It probably costs a little bit extra because the store has to pay for these single use cups that they give out. And there’s environmental costs associated with these that you pay in your taxes, you pay in your garbage bills, and whatever. So I like the idea of using the market as a way to alert people to the fact that this stuff has a cost. And I also really believe that all of us are penny-pinchers. And if we’re forced to pay five or ten cents for a plastic bag, or pay an added premium to get it in a non-reusable cup, that’s going to make people think a little bit. It’s not going to drive them off the scene. And some people just want to completely get rid of them. But it does reduce them. In Ireland, that “plastax” — that twenty-five cent fee on plastic bags, that dropped the use of plastic bags by about 90% in its first few months. In Washington DC, where it’s just five cents on plastic bags, they’ve substantially reduced the plastic bags. And that’s money being collected to clean up the Anacostia River.

Correspondent: Yes. Let’s go to the beginning, so to speak. You point out that the plastics industry was, in its early days, monopolized by the military. Largely from the 1930s through World War II. After this production, hey, no war is on! So let’s transfer it to the consumer market! You suggest that much of this had to do with, as you say, “a public weary of two decades of scarcity.” I’m wondering how much of this had to do with just the industry wanting to sustain a production level that was equal or greater to what it had going during the war. I mean, war is very profitable!

Frienkel: War is very profitable. What actually happened was that a lot of the plastics that are the modern plastics that we come into contact with every day today. A lot of those were actually invented in the 20s and 30s and didn’t really get into circulation. Because World War II came along. And the military substituted plastics for a lot of strategic materials. And I don’t think that there was any great conspiracy. You had this huge production capacity built up and the companies needed to find markets. And at the same time, again, you have this new lifestyle developing that was very amenable. Suddenly, people had a lot of money in their pockets. They were moving out to the suburbs. They were buying homes. There was a whole society and economy built and gearing up for consumption. And the plastics made that really possible and helped that.

Frienkel: War is very profitable. What actually happened was that a lot of the plastics that are the modern plastics that we come into contact with every day today. A lot of those were actually invented in the 20s and 30s and didn’t really get into circulation. Because World War II came along. And the military substituted plastics for a lot of strategic materials. And I don’t think that there was any great conspiracy. You had this huge production capacity built up and the companies needed to find markets. And at the same time, again, you have this new lifestyle developing that was very amenable. Suddenly, people had a lot of money in their pockets. They were moving out to the suburbs. They were buying homes. There was a whole society and economy built and gearing up for consumption. And the plastics made that really possible and helped that.

Correspondent: But was it really about consumer spending and upward mobility? I mean, the public rejected plastic for a long period of time. And when companies such as DuPont started thinking very small — such as the disposable lighter — and also thinking very low-cost, this was when the public snatched it up. So was it really a matter of forcing all these low-cost goods such as the monobloc chair or the disposable lighter onto the markets? So that they would have to buy it?

Freinkel: I don’t think — the public didn’t reject plastic. They just didn’t have them there. You had celluloid and Bakelite and a few other plastics out there in the early decades of the 20th century. But they just weren’t there yet. And the production capacity, you didn’t literally have the technology to make stuff out of a lot of these new plastics. And a lot of that technology got perfected in the process of serving the needs of World War II. In some cases, you would have products that really got foisted onto the public. Plastic bags were foisted onto the public. Polyethylene companies — they gradually replaced paper bags with plastic baggies. They replaced paper dry cleaning bags with plastic dry cleaning bags. They replaced newspapers that people used to use to line garbage bins with big Hefty bags. And there was a very deliberate and strategic decision that, now, the next front was the checkout stand. And they were going to develop a plastic bag. They found a plastic bag in Europe and brought it to the States and went to great efforts. I mean, some of these companies sent trainers to the grocery stores. To train grocery stores how to pack these bags so that customers wouldn’t get ticked off that the bags tipped over. That was a very deliberate decision. And that was one in which people’s choices really got limited. Because soon grocery stores were only using plastic bags. And in other cases, with something like the disposable lighter, that’s just pure convenience. And again there were campaigns with the disposable lighter. When there’s convenience and when there’s abundance on the cheap, it’s never been unappealing to people.

Correspondent: Well, in the case of the disposable lighter, as you point out in the book — you know, I used to be a smoker. And Zippos were far more effective than any disposable lighter. Especially that really kickass sound.

Freinkel: Did you use Zippos?

Correspondent: I did use a Zippo. Until I lost it. And then I went back to disposable. Cigarettes went up here, thank goodness. I don’t smoke anymore. But the point is that there was a durability quality that had to be replaced with cheap. Was it a matter of flooding the market with cheap goods? Or was it a matter of training, so to speak, the consumer in almost a Bernaysian-like fashion? “Oh, hey! This is so instant. Disposable’s okay.” You have that photo that you allude to in the book.

Freinkel: Right. I think there was a whole push starting in the late 50s. Immediately after the war, the first push was to put plastics into durables. And then I think there was this recognition on the part of the industry that, if you want to keep going in the market, disposability was the way to go. But I don’t mean to paint that as some grand conspiracy. Because I think it fit really well into, and was appealing to the kind of society that we were becoming. Soda bottles, another one of the objects that I look at in the book. Those replaced glass bottles, which the beverage companies started getting rid of in the 50s. Why were they getting rid of them? Partly because the interstate highway system enabled them not to have to send all those back across huge regions to bottlers and bottle washers. They could now have more fragmented distribution facilities. And you started having one way bottles instead of glass. And into plastic. So it’s like disposable diapers. What parent hasn’t loved disposable diapers? For all of the environmental cost, it sure is a lot easier than cloth diapers. Is that an industry conspiracy? Well, Kimberly Clark and the other companies saw a niche and parents loved them.

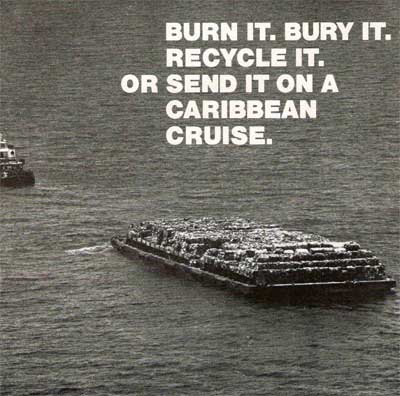

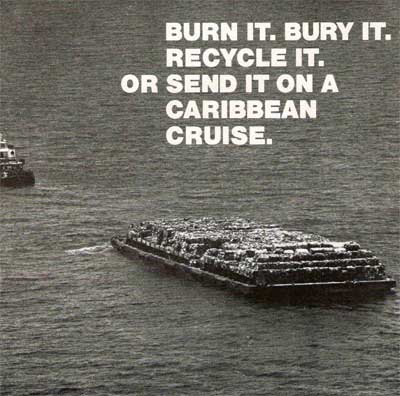

Correspondent: I don’t wish to imply that it’s a conspiracy. I’m more just thinking in terms of what a business is thinking versus what a consumer is thinking. And maybe I have another way of getting at this issue by bringing up packaging. Which as you point out is one of the largest portions of the waste system. Up until the early 20th century, as you point out in the book, people tended to maintain this informal recycling system. They would reuse material. They would find new ways of putting things to use. But I’m wondering: if it takes a Mobro 4000 going up and down the East Coast or, hey, there’s all these gyres! There’s all these garbage patches in the ocean. Does it take this kind of visibility to get people to rethink their disposable habits? What happened here? Can we blame the perception of regular people who are starting to understand that there’s a consequence to their behavior? Or can we also blame governments and corporations that failed to employ enough safeguards or failed to predict the consequences of a sheer mass production in plastic?

Correspondent: I don’t wish to imply that it’s a conspiracy. I’m more just thinking in terms of what a business is thinking versus what a consumer is thinking. And maybe I have another way of getting at this issue by bringing up packaging. Which as you point out is one of the largest portions of the waste system. Up until the early 20th century, as you point out in the book, people tended to maintain this informal recycling system. They would reuse material. They would find new ways of putting things to use. But I’m wondering: if it takes a Mobro 4000 going up and down the East Coast or, hey, there’s all these gyres! There’s all these garbage patches in the ocean. Does it take this kind of visibility to get people to rethink their disposable habits? What happened here? Can we blame the perception of regular people who are starting to understand that there’s a consequence to their behavior? Or can we also blame governments and corporations that failed to employ enough safeguards or failed to predict the consequences of a sheer mass production in plastic?

Freinkel: Well, I think one of the points that I make in the book is that, if you look at packaging, packaging and manufactured products are the major part of the waste stream now. And that wasn’t true a hundred years ago. And what that has done in terms of who deals with that waste is, as you put, what someone would argue as a kind of unfunded mandate on local governments. Because all this packaging and all these disposable manufacturing products go into the waste stream. And it’s on the backs of municipal governments to deal with them. In some places, they have effective recycling programs that can deal with that waste. But for the most part, they don’t. And they just landfill it. I think one of the answers to that is that you have companies be held financially responsible for the packaging products in the marketplace. And when you say to a company, “Great. You can package this thing any way you want. But you’re going to have to pay for getting that packaging back. And you’re going to have to pay for the recycling and the disposing of it,” well guess what happens? What Europe has found is that, when you do that, companies are a lot more prudent with their packaging. They use much more recyclable materials. Recycling rates go up. There are nice cascading effects that come out of that. And you no longer have municipal governments and consumers/taxpayers carrying the burden of this kind of waste that we didn’t ask for. I mean, we don’t have a choice when we go into a store of what kind of packaging. We can say, “I’m not going to buy this overpackaged thing.” But we’re limited by the choices of what’s on the shelves. And if it’s all overpackaged stuff, that’s all we have to deal with.

Correspondent: Well, we may be limited, say, in terms of buying produce. That’s a terrible thing, where you have to put all the produce in separate plastic bags so that the checker knows which produce is which. But on the other hand, you can do what I do. We go shopping and we bring our backpacks. And instead of using this wasteful plastic, we put the groceries into the backpacks. On the other hand, Styrofoam nuggets and all this wasteful packaging — this isn’t exactly a new situation. This has been going on for decades. Why do you think there has been a lack of awareness or a lack of enforcement or a lack of appropriate legislation to respond to the obvious glut of waste that comes from something like this?

Freinkel: You know, it’s funny. It wasn’t until I started researching this book that I realized the issues that are coming up now have come up before. And there’s been at least two cycles of outrage over packaging and fast food packaging and so forth.

Correspondent: Twenty year cycles there. (laughs)

Freinkel: You know, the first was in the 50s, where there was this whole hysteria of dry cleaner bags. Infants had choked, suffocating on dry cleaning bags that parents were following the instructions on the bags: reuse. And they were using them to cover their cribs. And their babies were horribly suffocated. And those incidents sparked legislation to ban plastic dry cleaner bags. And the plastics industry fought back very hard. PR. All these campaigns to quelch those efforts to ban the bag. And that’s been the pattern that’s come up. In the late 80s, Suffolk County, New York was the very first place to propose a ban on takeout containers. And the plastics industry took them to court. And by the time the court case got settled, they also poured money into the recycling industry and started to build up a recycling infrastructure. By the time the court case resolved, which was four years later, Suffolk County had the court’s okay to go ahead with the legislation. But public interest had moved onto other stuff. The Mobro 4000 barge had sparked a lot of interest in the late 80s. And that petered out. Now, I argue, we’re really seriously at a turning point. And I think the specter of all this plastic in the ocean — this huge vast areas, where you’ve got the water swirling with plastic bits — really speaks to the long reach of our waste and our stupid use of plastic. Whether this has more staying power, I don’t know. Once again, the plastics industry is responding with a renewed push for recycling, though not putting a lot of money into recycling. You have the sustainability buzz word that’s in business. Because companies now see that it’s in their financial best interest to reduce packaging. You know, you hope that it lasts. But I don’t know. If I was looking at the history of this, I would be quite cynical about it.

Freinkel: You know, the first was in the 50s, where there was this whole hysteria of dry cleaner bags. Infants had choked, suffocating on dry cleaning bags that parents were following the instructions on the bags: reuse. And they were using them to cover their cribs. And their babies were horribly suffocated. And those incidents sparked legislation to ban plastic dry cleaner bags. And the plastics industry fought back very hard. PR. All these campaigns to quelch those efforts to ban the bag. And that’s been the pattern that’s come up. In the late 80s, Suffolk County, New York was the very first place to propose a ban on takeout containers. And the plastics industry took them to court. And by the time the court case got settled, they also poured money into the recycling industry and started to build up a recycling infrastructure. By the time the court case resolved, which was four years later, Suffolk County had the court’s okay to go ahead with the legislation. But public interest had moved onto other stuff. The Mobro 4000 barge had sparked a lot of interest in the late 80s. And that petered out. Now, I argue, we’re really seriously at a turning point. And I think the specter of all this plastic in the ocean — this huge vast areas, where you’ve got the water swirling with plastic bits — really speaks to the long reach of our waste and our stupid use of plastic. Whether this has more staying power, I don’t know. Once again, the plastics industry is responding with a renewed push for recycling, though not putting a lot of money into recycling. You have the sustainability buzz word that’s in business. Because companies now see that it’s in their financial best interest to reduce packaging. You know, you hope that it lasts. But I don’t know. If I was looking at the history of this, I would be quite cynical about it.

Correspondent: Yeah. One thing I did not know until I read your book, and it seems rather obvious in hindsight and it makes perfect sense: if China is flooding the United States with all these cheap goods, well they have to take something back. And I was alarmed to learn that they’re taking 70% of the world’s used plastics and a good chunk of what we use here. When we think of something like that, is it really a matter of all these issues hiding in plain sight? Why isn’t there a discussion about the way we use something as obvious as plastic cups and the like? We’re starting here, I guess. (laughs)

Freinkel: I’m hoping to start that conversation. Because I think it’s an important conversation. Unfortunately, I think it’s been a long time. It’s kind of the province of the left and environmental activists. And even then, I think there’s a huge amount of misinformation about plastic. There’s a lot of people who look at things like the Pacific Gyre and say, “Well, I just don’t want anything to do with plastic.” Which is, in its own way, as wrongheaded as saying, “This isn’t a problem. I don’t need to worry about it.” I don’t know. It varies from place to place. In San Francisco, for instance, we have very aggressive recycling. And we walk down the street. And there are recycling cans all along the street. We were walking around Brooklyn today. And both my daughter and I were noticing that there’s no recycling cans. It just goes in the trash.

Freinkel: I’m hoping to start that conversation. Because I think it’s an important conversation. Unfortunately, I think it’s been a long time. It’s kind of the province of the left and environmental activists. And even then, I think there’s a huge amount of misinformation about plastic. There’s a lot of people who look at things like the Pacific Gyre and say, “Well, I just don’t want anything to do with plastic.” Which is, in its own way, as wrongheaded as saying, “This isn’t a problem. I don’t need to worry about it.” I don’t know. It varies from place to place. In San Francisco, for instance, we have very aggressive recycling. And we walk down the street. And there are recycling cans all along the street. We were walking around Brooklyn today. And both my daughter and I were noticing that there’s no recycling cans. It just goes in the trash.

Correspondent: Well, to be clear on how it operates in Brooklyn, it’s really ridiculous actually. If you want to get your stuff picked up, you have to put it in a very specific bag. And even then, it all depends on the person who’s picking it up. They often won’t pick up your stuff. And so your stuff has to sit there. And you basically play this Russian roulette, hoping that they’ll pick it up one of the three days — Monday, Wednesday, or Friday. I’ve had stuff out there for two weeks. And the thing is, there’s no agreed upon conformity of the method in which one picks up cans and bottles.

Freinkel: It’s a total patchwork in this country. There are only ten states that have bottle bills where you can redeem bottles. And those have much higher recycling rates for those bottles, even if they don’t have good recycling rates for other types of plastics. You know, I think part of the problem is, because so much plastic goes into the cheap stuff, we consider it a junk material. Look at a lot of our waste. We just don’t think of waste as a resource. And instead of looking at this as stuff that you can mine for all sorts of useful purposes, we’re just very happy burning and burying them. That’s not just plastic. That’s also electronics. It’s metal. It’s fabric. Again, the way that we treat plastic is emblematic of the whole mindset that has evolved in the last fifty years. And this is very different from what our great grandparents lived by. By the ethics of reuse and conservation.

Correspondent: Let’s talk biodegradability. You point out that it does indeed have its problems. You write that even though plastic is more difficult to break down than wood, the biodegradability is a function of a polymer’s structure rather than its starting ingredients. You use the example of a tree toppling in the desert. There aren’t any microorganisms there to go ahead and eat it up. Therefore, you have petrified wood. Why is petrified wood any worse than nonbiodegradable or even slowly biodegradable plastic?

Freinkel: Well, there’s a whole lot less petrified wood than there is plastic. I think that’s the main issue. We don’t find petrified wood everywhere. And if it gets in the ocean, it might still be petrified wood. But the problem with nonbiodegradable plastic is that so much of it ends up in the environment. So much of it ends up in the ocean, where there’s really no method to break it down. And then it just fragments into smaller and smaller fragments. And the fear is that it can get into the food web. But biodegradable plastics, what they solve depends on what your problem is. I shouldn’t say biodegradable plastics. I should say bioplastics. Plant-based plastics. If you’re looking for a plastic that’s going to break down, there’s no guarantee just because you’re using plants as opposed to fossil fuels that’s going to biodegrade, if you’re looking for plastic that has a lower carbon footprint, you’re better off with that. If you’re looking for plastic that’s cleaner and is less likely to contain troublesome or toxic chemicals, that totally depends on how that bioplastic is made. I mean, that’s the thing about plastic. We talk about plastic like it’s one thing. But there’s a lot of different types of plastic out there. And we talk about the problems that plastics generate. And there’s a lot of different solutions. There’s not a silver bullet answer to all the problems associated with plastic.

Correspondent: Well, since you brought up bioplastics, let’s talk about that as well. You write that these bioplastics “may or may not be an improvement on their fossil fuel-based relatives.” In the interest of getting more specificity here, are there any disadvantages to bioplastics? Is it essentially that uncertainty? It may be a lower carbon footprint, but is it really better when compared to fossil fuels?

Freinkel: Well, it’s funny that you bring that up. Because I was just writing a little blog post about compostable dog poop bags.

Correspondent: Aha!

Frienkel: Which are the hot thing. Everybody who’s got a dog is thinking, “Oh, you know, I should get one of these disposable bags. And those are great if you live in a city which will compost them. Or you put them on your backyard compost. But if you take those compostable dog poop bags and throw them in the trash, and think “at least they won’t last in the landfill forever,” well, you actually don’t want things to biodegrade in the landfill. Because in the atmosphere of the landfill, once something biodegrades, it generates methane. Which is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. So I think we need to create a new generation of plastics that are true cradle-to-cradle plastics, where they can either be recycled back in the industry or they can be recycled back into nature, composting or whatever. That could move a lot of different plastics. There’s no one single bioplastic that’s going to serve that purpose. Coca-Cola has their plant bottle — this much ballyhooed plant bottle which is made from plant-based plastics. And they’ve come under fire. Because people say, “It’s just like regular PET plastic. It’s not a totally new plastic. It’s not biodegradable.” But to a lot of people, and I kind of agree with them, at least it’s a recyclable plastic. And it fits very easily into a pretty well developed recycling strain. Right now, the technology is ahead of the infrastructure that we need to have support it. Compostable plastics only really make sense if you have a composting infrastructure. And that doesn’t exist in many parts of the country right now.

Frienkel: Which are the hot thing. Everybody who’s got a dog is thinking, “Oh, you know, I should get one of these disposable bags. And those are great if you live in a city which will compost them. Or you put them on your backyard compost. But if you take those compostable dog poop bags and throw them in the trash, and think “at least they won’t last in the landfill forever,” well, you actually don’t want things to biodegrade in the landfill. Because in the atmosphere of the landfill, once something biodegrades, it generates methane. Which is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. So I think we need to create a new generation of plastics that are true cradle-to-cradle plastics, where they can either be recycled back in the industry or they can be recycled back into nature, composting or whatever. That could move a lot of different plastics. There’s no one single bioplastic that’s going to serve that purpose. Coca-Cola has their plant bottle — this much ballyhooed plant bottle which is made from plant-based plastics. And they’ve come under fire. Because people say, “It’s just like regular PET plastic. It’s not a totally new plastic. It’s not biodegradable.” But to a lot of people, and I kind of agree with them, at least it’s a recyclable plastic. And it fits very easily into a pretty well developed recycling strain. Right now, the technology is ahead of the infrastructure that we need to have support it. Compostable plastics only really make sense if you have a composting infrastructure. And that doesn’t exist in many parts of the country right now.

Correspondent: Capitalism seems to be one of the key problems in maintaining a feasible recycling system. Aside from the fact that you have companies like Coca-Cola more likely to manufacture more expensive bioplastics or even ban plastic bags when they’re told by the government, you discovered in San Francisco, when you followed the recycling people, that the homeless are swiping a good chunk of the cans and the bottles. And in San Francisco, the state of California is getting the lion’s share of all this recycling revenue. Because the homeless pick it up. And then San Francisco loses five million dollars a year to professional poachers. You grabbed those figures in May 2010. Has there been any traction in the last year to sort out this disparity between state and local governments. I know California is in a bit of a clusterfuck right now. (laughs)

Freinkel: I know. There are so many problems associated with California and its redemption problem. If I remember right, I think Arnold Schwarzenegger took money out of that program to cover other deficits in the budget. It’s kind of a mess. But the amount that a homeless guy or even these professional poachers pull out, they’re pulling it out of — it’s actually not a City-run program; it’s a private company that contracts with the City — I don’t really fault those guys. I mean, they’re taking advantage of an economy that exists. You know, they’re recognizing what a lot of people don’t recognize. Which is that this stuff has value.

Correspondent: But on the other hand, when you’re dealing with the idea that this has value — we can’t actually put this back into the system so that it comes back into the City and the like — you have a problem in maintaining a system through one authority, whether it be the City or a private industry. The sense I get from your book is that, even if you can get people to agree on something, you’re going to have situations along these lines. You’re going to have problems unless you have hard enforcement, as we saw with Ireland and also with the Green Dot Program. But going back to California, I’m wondering if it’s even possible for California to come up with a recycling system that is financially self-sustaining for resident, for recycler, and for poacher. Do you have any ideas?

Freinkel: I really don’t. Great idea? I don’t know. To me, the biggest issue in recycling is developing those secondary markets. Right now, the only really sustainable secondary markets are for PET plastics, the stuff that soda and water bottles are made out of, and high density polyethylene, like milk jugs and detergent bottles. But there’s still a whole lot of other plastics that we don’t have secondary markets for. And if they can’t be developed, then maybe we shouldn’t be using them so much. And California, I know, at one time, they were putting money into trying to stimulate these secondary markets for particularly kinds of plastics. I don’t really know how much is happening right now.

Correspondent: Can private industry offer a solution where California can’t?

Freinkel: If private industry stepped up to the bat, if the makers of polypropylene stepped up to the bat, it would be very helpful. Actually, there’s this private program. Polypropylene is #5 plastics. It’s the stuff used in yogurt containers. It’s a great plastic. It’s a very clean plastic. And there’s a company called Preserve that was founded by this guy in Boston who was disturbed by the fact that it’s almost never recycled. Because there are very few secondary markets. But it’s a very processable plastic. So he started this company and started trying to collect polypropylene and he started off making toothbrushes and trying them in Whole Foods. And it’s since developed into this program where Whole Foods and Stonyfield Yogurt, where they’ve got this program called Gimme 5 that encourages people to bring back yogurt containers that can then be recycled by Preserve. And toothbrushes. And cutlery. As far as I know, that’s mostly a private program in which private businesses step up to the bat. It’s sort of win win for everybody.

Freinkel: If private industry stepped up to the bat, if the makers of polypropylene stepped up to the bat, it would be very helpful. Actually, there’s this private program. Polypropylene is #5 plastics. It’s the stuff used in yogurt containers. It’s a great plastic. It’s a very clean plastic. And there’s a company called Preserve that was founded by this guy in Boston who was disturbed by the fact that it’s almost never recycled. Because there are very few secondary markets. But it’s a very processable plastic. So he started this company and started trying to collect polypropylene and he started off making toothbrushes and trying them in Whole Foods. And it’s since developed into this program where Whole Foods and Stonyfield Yogurt, where they’ve got this program called Gimme 5 that encourages people to bring back yogurt containers that can then be recycled by Preserve. And toothbrushes. And cutlery. As far as I know, that’s mostly a private program in which private businesses step up to the bat. It’s sort of win win for everybody.

Correspondent: Well, what about carnival barkers, such as this guy Roger Bernstein from the American Chemistry Council? I thought he was quite interesting. You point out that he sees paper vs. plastic fights as sideshows. How much of this is reflective of American recycling policies? Is there a particular temperament or precedent in American policy that causes these carnival barking, sideshow, big blowups at town hall meetings and the like that you don’t see in Europe? Europe effectively mandates and introduces things such as the Green Dot Program.

Freinkel: Well, Europe has a more European policy that tends to have more government involvement instead of that ideology of rugged individualism.

Correspondent: Especially in California too.

Freinkel: Yeah. There isn’t that same, really strong commitment to letting the free market have its way. And so I think it’s easier for Europe to get these sorts of things true. Europe also has a problem that the US doesn’t, which is that they have almost no landfill space. So dealing with waste has a kind of urgency in Europe that it just doesn’t here — particularly the further west you go, where there’s just eminent room to go. Again, I think it’s not just plastic. It’s nuclear technology. We build nuclear power plants and say, “Oh, we’ll find a good place to bury this stuff. Eventually somebody will take it.” It’s a kind of mentality. We don’t like to look at ways to deal with waste and think through full implications.

Correspondent: But you’re giving me so many fantastic ideas! We could just ban the usage of all landfills and have this Wall-E situation where every amount of trash that we produce is right outside our homes! And then suddenly we see that there’s an actual consequence to this.

Freinkel: I think we’ll have to. At the end of the book, I did this challenge. This woman, Beth Terry, who you mentioned at the start, has been trying to go plastic free and has dramatically reduced the amount of plastic she uses. She is so far beyond anything that I ever tried. But Beth, on her blog, challenges people to spend a week collecting plastic trash. So you can just see what you’ve got there. And I resisted doing this. Because I just knew that it was going to be ugly. And at the end of my research, I said, “Okay, I’ll take the challenge.” And sure enough, I had this huge pile of stuff. And aside from the fact that it was a lot of waste, it also reflected a lot of waste. It reflected the fact that I was buying stuff that I didn’t really need or that I was throwing out bread because my kids won’t eat the heels. I had been throwing out food that had gotten to the back of the refrigerator. I had forgotten about it and now I had to toss it, along with the dirty wrapper.

Correspondent: You really should be baking your own bread, Susan.

Freinkel: (laughs)

Correspondent: We all should be. That would solve a lot of problems.

Freinkel: I mean, we have to figure out where we’re going to draw the line and how extreme we want to be. And I don’t know if I want to bake my own bread. Because I really like that bread from the bakery. But I could also be much careful about how much I buy and be more mindful about the way that I do this.

Correspondent: So you’re advocating communes and geodesic domes?

Freinkel: (laughs)

Correspondent: Is that what’s going on here?

Freinkel: Not quite. I’m just advocating going to the store and being more careful about how you use stuff. And if you want to take it further than that. I don’t want to make my own ketchup and my own deodorant, which is what some people do. But I can buy my grains and my ketchup in bulk and not buy the packets. I don’t have to buy the snack packs.

Correspondent: On the other hand, that is the kind of luxury that someone who is middle class or upper class can take. At Grand Army Plaza, which is north of Park Slope, there’s a farmers market. I went by there with some friends this last weekend and the prices had jacked up considerably to have this organic stuff in the last six months. So if you want to go ahead and live green and live fresh and live responsibly, and get away from the “lifestyle,” it literally creates a new affluent lifestyle that not everybody is going to be able to afford.

Freinkel: Absolutely. As I mentioned earlier, if you want to buy household cleaners that are cheaper and don’t have all sorts of toxic crap in them, those typically cost more. And not everybody is going to do that. And people live in poor neighborhoods generally don’t have access. If there’s a grocery store, it’s going to be a pretty crappy grocery store. And it’s not going to have a lot of fresh produce or organic produce.

Correspondent: We’ll have to become farmers. You point out that while experts have discovered some of the chemicals used in IV bags, kitchenware, toys, and furniture fire retardants are harmful, we don’t really know the full health implications of our exposure to all these plastic chemicals. How has this industry been allowed to flourish without considering, “Well, if we’re putting our food or our clothes or our bodies into these plastic environments, maybe we should think about what we’re doing here”? Has oversight mostly been passed on to private industry for this?

Correspondent: We’ll have to become farmers. You point out that while experts have discovered some of the chemicals used in IV bags, kitchenware, toys, and furniture fire retardants are harmful, we don’t really know the full health implications of our exposure to all these plastic chemicals. How has this industry been allowed to flourish without considering, “Well, if we’re putting our food or our clothes or our bodies into these plastic environments, maybe we should think about what we’re doing here”? Has oversight mostly been passed on to private industry for this?

Freinkel: There is no oversight. Stuff that comes into contact with food goes to the FDA. And there’s some debate about how well they study it. But the main chemical law in the country — the Toxic Substances Control Act — was passed in 1976. At that time, there were about 60,000 chemicals in commerce. They were all grandfathered in under the Act. They didn’t have to be subjected to any kind of market review. And it’s estimated that another 20,000 or so have been developed and brought into the market since then with very minimal oversight. The basic crux of the law is a chemical is assumed to be safe unless it’s proven to be otherwise. But the way the law is written, it’s very difficult to establish that it may not be safe. And of those 20,000 chemicals, the EPA has only been able to get reviews from about 200. And the law is so toothless that the Agency could not have even successfully bar asbestos, which is an incontrovertible carcinogenic. So it’s just a law that pretty much has let industry have free reign. And as a consequence, we don’t really know what chemicals we’re being exposed to. You buy a plastic product. [pointing to cup] There’s nothing on this plastic cup to tell me what might be in this. What chemicals might be in it. Presumably because it’s got food in it, I can hope that it’s a safe plastic because the FDA has said that it’s a safe plastic. But otherwise, there’s nothing on this microphone [gesturing to my mike, worried expression from me about the dust that has accumulated on the windscreen] to indicate what plastic chemicals there may be.

Correspondent: Well, you’ve lost two days of your life by talking with me in this environment.

Freinkel: (laughs)

Correspondent: But on the other hand, you did point out in the book that Europe banned DEHP from children’s toys nine years after America did.

Freinkel: Nine years before.

Correspondent: Nine years before! I’m sorry. Well, what are some of the differences in terms of getting legislation oversight from Europe?

Freinkel: Europe has more of a history and some ideological predisposition toward more government intervention policies. Europe has passed a set of chemical policies where they take what’s called a cautionary approach. And the assumption is that, if there is suspicion that a chemical is dangerous, if there is some indication that a chemical is dangerous, it’s up to the manufacturer to prove that it’s not. So the burden is on the manufacturer to prove safety rather than on the government or the regulators to prove lack of safety. What that means is that they take much tighter and harder scrutiny of chemicals that come through. Now that’s just sort of getting underway. And it’s unclear what the final result of it is. Because some of the chemicals have been really controversial in this country, Europe has said it’s simply not worth the risk. That said, not only do we not know the chemicals that are in plastics, but we just really don’t know if they’re dangerous. DEHP, this softener that’s used in vinyl, there’s a lot of suggestive evidence that it may be an endocrine disrupter, that it may interfere with testosterone in the body, and that may have an effect on reproductive health in boys and men.

Correspondent: Don’t say that to me! (laughs)

Freinkel: We don’t know for sure. But the effects are subtle. These aren’t chemicals that are going to cause this massive wave of cancer. Not like asbestos, where you can draw a straight line. It’s more subtle.

Correspondent: Good. I was getting concerned about my virility.

Freinkel: (laughs) Well, it must have been like chewing on vinyl every day. You’re probably okay.

Correspondent: All those vinyl collectors. (laughs) Well, your book closes with the Wharton State Forest Bridge, a crossing that has been constructed entirely of recycled plastic that costs less to build than bridges, such as our lovely three crossing from here into Manhattan — the Brooklyn, the Manhattan, and the Williamsburg Bridges. But since plastic itself is so new, and we’re only just comprehending its environmental effects, how can we know that these plastic bridges will last as long as the 200 years that the engineers say they will? I mean, I also understand that some of the recycled plastic is being held up by fiberglass. Because there’s this creep that kicks in. And that’s also vinyl ester that they’re using in the fiberglass. So we may be reusing our resources. But could it just be as reckless as not knowing the plastic chemicals around us?

Freinkel: I guess that’s conceivable. That bridge is a short bridge. You’re not going to replicate the Manhattan Bridge or the Tappan Zee out of fiberglass.

Correspondent: I’d like to see them try the Brooklyn or the Golden Gate. (laughs)

Freinkel: It certainly wouldn’t be this beautiful kind of structure. The guy who invented the process for recycling plastics — I mean, he took milk jugs and car bumpers. The guy who invented that process claims that he has solved the problem of creep and that these are, in fact, really strong, really durable bridges. I mean, time will tell. It’s hard to know. Certainly I don’t see any reason to think that they’re going to have the kind of chemical footprint of chemically treated wood. But you’re right. There is a risk there. All we can sort of go for right now — those aren’t generally plastics that have a lot of stuff in them to leach out. Milk jugs are made up of polyethylene. Again, it’s a pretty clean plastic. I use the bridge. I close the book with the bridge really as a way to suggest rather than taking this kind of fabulous material and putting it into a milk jug that will end up in a landfill and maybe some future generation 200 years from now will come across this layer of plastic wrap and wonder what the hell is this thing. Put it into something that is meant to last and take advantage of the fact that it lasts a long time.

Correspondent: Well, it’s certainly a more efficient use of government resources than the Bridge to Nowhere. Susan, thanks so much. It was a pleasure chatting with you.

[Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to DDHT as “the softener that’s used in vinyl.” It has been corrected to DEHP.]

Correspondent: You write that Scientology “was not a ‘cult’ insofar as it did not require separation from mainstream society — though it encouraged its acolytes to ‘disconnect’ from those who were critical of Scientology.” Now sociologist Howard Becker’s idea of a cult generally emphasizes the private nature of personal beliefs or a group of people that isn’t especially organized. Given how private and sequestered Scientologists are about their beliefs, I’m wondering. If you took away the organization, could you call them a cult? How is Scientology not a cult?

Correspondent: You write that Scientology “was not a ‘cult’ insofar as it did not require separation from mainstream society — though it encouraged its acolytes to ‘disconnect’ from those who were critical of Scientology.” Now sociologist Howard Becker’s idea of a cult generally emphasizes the private nature of personal beliefs or a group of people that isn’t especially organized. Given how private and sequestered Scientologists are about their beliefs, I’m wondering. If you took away the organization, could you call them a cult? How is Scientology not a cult? Reitman: I don’t think any of it was designed as “a matter of practical business” originally. I mean, I think that L. Ron Hubbard grew up in the ’20s. He was born in 1911. He essentially grew up, so to speak, into the ’20s and the ’30s during the Depression. He was a young man in the Depression. And he found himself in Los Angeles after World War II. And Los Angeles, during that period of the mid to late ’30s and the ’40s (and also the ’20s), was this booming religious ground, where all kinds of weird offshoot faiths, new faiths and offshoots of Christianity as well, were then really popular. And one of those areas was the Western esoteric tradition that he found himself getting to know very well through this association he had with Jack Parsons, who was a famous astrophysicist and secret wizard. Follower of Aleister Crowley. It’s one of everybody’s favorite stories: L. Ron Hubbard’s association with Jack Parsons. But I think that he took those aspects of esoteric thought, which were things like secret knowledge, ascending the ranks to gain more and more knowledge. And that was very common in L.A. It wasn’t just through Crowley. The Rosicrucians had a big church. There were lots of societies that were based on that kind of tradition. The sort of alternative, new-agey stuff that was really popular in the early 20th century and then became popular again towards the end of the 20th century. And I think that Hubbard was a guy who was really interested in philosophy and was interested in power. And he took probably some of the best parts, as well as some of the dysfunctional parts in terms of Freudian thoughts that Freud had discarded years earlier. But he took a wide variety of ideas. He manufactured them in a way that made them palatable to people who were not well-educated. That’s very important to know. People who did Scientology were very middle-class. They weren’t uneducated people. Some of them were extremely well-educated. But they were, for the most part, very average, mainstream in that this was religion or this was self-help or psychiatry, or an alternative to psychiatry for the masses. And at the time, these things were very exclusive. You couldn’t do psychiatry for example. You couldn’t go to a psychiatrist unless you had a tremendous amount of money to pay for a psychiatrist. There were only a few psychiatrists even in the United States practicing.

Reitman: I don’t think any of it was designed as “a matter of practical business” originally. I mean, I think that L. Ron Hubbard grew up in the ’20s. He was born in 1911. He essentially grew up, so to speak, into the ’20s and the ’30s during the Depression. He was a young man in the Depression. And he found himself in Los Angeles after World War II. And Los Angeles, during that period of the mid to late ’30s and the ’40s (and also the ’20s), was this booming religious ground, where all kinds of weird offshoot faiths, new faiths and offshoots of Christianity as well, were then really popular. And one of those areas was the Western esoteric tradition that he found himself getting to know very well through this association he had with Jack Parsons, who was a famous astrophysicist and secret wizard. Follower of Aleister Crowley. It’s one of everybody’s favorite stories: L. Ron Hubbard’s association with Jack Parsons. But I think that he took those aspects of esoteric thought, which were things like secret knowledge, ascending the ranks to gain more and more knowledge. And that was very common in L.A. It wasn’t just through Crowley. The Rosicrucians had a big church. There were lots of societies that were based on that kind of tradition. The sort of alternative, new-agey stuff that was really popular in the early 20th century and then became popular again towards the end of the 20th century. And I think that Hubbard was a guy who was really interested in philosophy and was interested in power. And he took probably some of the best parts, as well as some of the dysfunctional parts in terms of Freudian thoughts that Freud had discarded years earlier. But he took a wide variety of ideas. He manufactured them in a way that made them palatable to people who were not well-educated. That’s very important to know. People who did Scientology were very middle-class. They weren’t uneducated people. Some of them were extremely well-educated. But they were, for the most part, very average, mainstream in that this was religion or this was self-help or psychiatry, or an alternative to psychiatry for the masses. And at the time, these things were very exclusive. You couldn’t do psychiatry for example. You couldn’t go to a psychiatrist unless you had a tremendous amount of money to pay for a psychiatrist. There were only a few psychiatrists even in the United States practicing.

Correspondent: This book started off with your own personal effort not to touch plastic. But even

Correspondent: This book started off with your own personal effort not to touch plastic. But even  Correspondent: (flourishing towards the plastic cups) I said, “She’s going to see me with this. And I’m going to be outed right here.” I’m thankful we’re both just as guilty here.

Correspondent: (flourishing towards the plastic cups) I said, “She’s going to see me with this. And I’m going to be outed right here.” I’m thankful we’re both just as guilty here. Freinkel: It sort of depends on what we’re talking about. So if we’re talking about something like plastic bags — single use plastics — I personally feel, I’m not big on the idea of bans. Because they really tick people off. And in San Francisco, the ban on the bag was just on plastic. It didn’t apply to paper bags. And consequentially, a lot of stores in San Francisco, and the stores — if they’re small stores, they’re still giving out plastic bags; if they’re the big chain stores, they’re giving out paper bags. And so people are still using single use bags. They’re not as resistant in the environment as the plastic. But they’re still paper. Part of the problem with single use stuff is that we get a lot of this stuff for free. And so we don’t actually have to think about the fact that they have costs. The cost is built into my ice coffee here. It probably costs a little bit extra because the store has to pay for these single use cups that they give out. And there’s environmental costs associated with these that you pay in your taxes, you pay in your garbage bills, and whatever. So I like the idea of using the market as a way to alert people to the fact that this stuff has a cost. And I also really believe that all of us are penny-pinchers. And if we’re forced to pay five or ten cents for a plastic bag, or pay an added premium to get it in a non-reusable cup, that’s going to make people think a little bit. It’s not going to drive them off the scene. And some people just want to completely get rid of them. But it does reduce them. In Ireland, that “plastax” — that twenty-five cent fee on plastic bags, that dropped the use of plastic bags by about 90% in its first few months. In Washington DC, where it’s just five cents on plastic bags, they’ve substantially reduced the plastic bags. And that’s money being collected to clean up the Anacostia River.

Freinkel: It sort of depends on what we’re talking about. So if we’re talking about something like plastic bags — single use plastics — I personally feel, I’m not big on the idea of bans. Because they really tick people off. And in San Francisco, the ban on the bag was just on plastic. It didn’t apply to paper bags. And consequentially, a lot of stores in San Francisco, and the stores — if they’re small stores, they’re still giving out plastic bags; if they’re the big chain stores, they’re giving out paper bags. And so people are still using single use bags. They’re not as resistant in the environment as the plastic. But they’re still paper. Part of the problem with single use stuff is that we get a lot of this stuff for free. And so we don’t actually have to think about the fact that they have costs. The cost is built into my ice coffee here. It probably costs a little bit extra because the store has to pay for these single use cups that they give out. And there’s environmental costs associated with these that you pay in your taxes, you pay in your garbage bills, and whatever. So I like the idea of using the market as a way to alert people to the fact that this stuff has a cost. And I also really believe that all of us are penny-pinchers. And if we’re forced to pay five or ten cents for a plastic bag, or pay an added premium to get it in a non-reusable cup, that’s going to make people think a little bit. It’s not going to drive them off the scene. And some people just want to completely get rid of them. But it does reduce them. In Ireland, that “plastax” — that twenty-five cent fee on plastic bags, that dropped the use of plastic bags by about 90% in its first few months. In Washington DC, where it’s just five cents on plastic bags, they’ve substantially reduced the plastic bags. And that’s money being collected to clean up the Anacostia River. Frienkel: War is very profitable. What actually happened was that a lot of the plastics that are the modern plastics that we come into contact with every day today. A lot of those were actually invented in the 20s and 30s and didn’t really get into circulation. Because World War II came along. And the military substituted plastics for a lot of strategic materials. And I don’t think that there was any great conspiracy. You had this huge production capacity built up and the companies needed to find markets. And at the same time, again, you have this new lifestyle developing that was very amenable. Suddenly, people had a lot of money in their pockets. They were moving out to the suburbs. They were buying homes. There was a whole society and economy built and gearing up for consumption. And the plastics made that really possible and helped that.

Frienkel: War is very profitable. What actually happened was that a lot of the plastics that are the modern plastics that we come into contact with every day today. A lot of those were actually invented in the 20s and 30s and didn’t really get into circulation. Because World War II came along. And the military substituted plastics for a lot of strategic materials. And I don’t think that there was any great conspiracy. You had this huge production capacity built up and the companies needed to find markets. And at the same time, again, you have this new lifestyle developing that was very amenable. Suddenly, people had a lot of money in their pockets. They were moving out to the suburbs. They were buying homes. There was a whole society and economy built and gearing up for consumption. And the plastics made that really possible and helped that.  Correspondent: I don’t wish to imply that it’s a conspiracy. I’m more just thinking in terms of what a business is thinking versus what a consumer is thinking. And maybe I have another way of getting at this issue by bringing up packaging. Which as you point out is one of the largest portions of the waste system. Up until the early 20th century, as you point out in the book, people tended to maintain this informal recycling system. They would reuse material. They would find new ways of putting things to use. But I’m wondering: if it takes a

Correspondent: I don’t wish to imply that it’s a conspiracy. I’m more just thinking in terms of what a business is thinking versus what a consumer is thinking. And maybe I have another way of getting at this issue by bringing up packaging. Which as you point out is one of the largest portions of the waste system. Up until the early 20th century, as you point out in the book, people tended to maintain this informal recycling system. They would reuse material. They would find new ways of putting things to use. But I’m wondering: if it takes a  Freinkel: You know, the first was in the 50s, where there was this whole hysteria of dry cleaner bags. Infants had choked, suffocating on dry cleaning bags that parents were following the instructions on the bags: reuse. And they were using them to cover their cribs. And their babies were horribly suffocated. And those incidents sparked legislation to ban plastic dry cleaner bags. And the plastics industry fought back very hard. PR. All these campaigns to quelch those efforts to ban the bag. And that’s been the pattern that’s come up. In the late 80s, Suffolk County, New York was the very first place to propose a ban on takeout containers. And the plastics industry took them to court. And by the time the court case got settled, they also poured money into the recycling industry and started to build up a recycling infrastructure. By the time the court case resolved, which was four years later, Suffolk County had the court’s okay to go ahead with the legislation. But public interest had moved onto other stuff. The Mobro 4000 barge had sparked a lot of interest in the late 80s. And that petered out. Now, I argue, we’re really seriously at a turning point. And I think the specter of all this plastic in the ocean — this huge vast areas, where you’ve got the water swirling with plastic bits — really speaks to the long reach of our waste and our stupid use of plastic. Whether this has more staying power, I don’t know. Once again, the plastics industry is responding with a renewed push for recycling, though not putting a lot of money into recycling. You have the sustainability buzz word that’s in business. Because companies now see that it’s in their financial best interest to reduce packaging. You know, you hope that it lasts. But I don’t know. If I was looking at the history of this, I would be quite cynical about it.

Freinkel: You know, the first was in the 50s, where there was this whole hysteria of dry cleaner bags. Infants had choked, suffocating on dry cleaning bags that parents were following the instructions on the bags: reuse. And they were using them to cover their cribs. And their babies were horribly suffocated. And those incidents sparked legislation to ban plastic dry cleaner bags. And the plastics industry fought back very hard. PR. All these campaigns to quelch those efforts to ban the bag. And that’s been the pattern that’s come up. In the late 80s, Suffolk County, New York was the very first place to propose a ban on takeout containers. And the plastics industry took them to court. And by the time the court case got settled, they also poured money into the recycling industry and started to build up a recycling infrastructure. By the time the court case resolved, which was four years later, Suffolk County had the court’s okay to go ahead with the legislation. But public interest had moved onto other stuff. The Mobro 4000 barge had sparked a lot of interest in the late 80s. And that petered out. Now, I argue, we’re really seriously at a turning point. And I think the specter of all this plastic in the ocean — this huge vast areas, where you’ve got the water swirling with plastic bits — really speaks to the long reach of our waste and our stupid use of plastic. Whether this has more staying power, I don’t know. Once again, the plastics industry is responding with a renewed push for recycling, though not putting a lot of money into recycling. You have the sustainability buzz word that’s in business. Because companies now see that it’s in their financial best interest to reduce packaging. You know, you hope that it lasts. But I don’t know. If I was looking at the history of this, I would be quite cynical about it. Freinkel: I’m hoping to start that conversation. Because I think it’s an important conversation. Unfortunately, I think it’s been a long time. It’s kind of the province of the left and environmental activists. And even then, I think there’s a huge amount of misinformation about plastic. There’s a lot of people who look at things like the Pacific Gyre and say, “Well, I just don’t want anything to do with plastic.” Which is, in its own way, as wrongheaded as saying, “This isn’t a problem. I don’t need to worry about it.” I don’t know. It varies from place to place. In San Francisco, for instance, we have very aggressive recycling. And we walk down the street. And there are recycling cans all along the street. We were walking around Brooklyn today. And both my daughter and I were noticing that there’s no recycling cans. It just goes in the trash.

Freinkel: I’m hoping to start that conversation. Because I think it’s an important conversation. Unfortunately, I think it’s been a long time. It’s kind of the province of the left and environmental activists. And even then, I think there’s a huge amount of misinformation about plastic. There’s a lot of people who look at things like the Pacific Gyre and say, “Well, I just don’t want anything to do with plastic.” Which is, in its own way, as wrongheaded as saying, “This isn’t a problem. I don’t need to worry about it.” I don’t know. It varies from place to place. In San Francisco, for instance, we have very aggressive recycling. And we walk down the street. And there are recycling cans all along the street. We were walking around Brooklyn today. And both my daughter and I were noticing that there’s no recycling cans. It just goes in the trash.  Frienkel: Which are the hot thing. Everybody who’s got a dog is thinking, “Oh, you know, I should get one of these disposable bags. And those are great if you live in a city which will compost them. Or you put them on your backyard compost. But if you take those compostable dog poop bags and throw them in the trash, and think “at least they won’t last in the landfill forever,” well, you actually don’t want things to biodegrade in the landfill. Because in the atmosphere of the landfill, once something biodegrades, it generates methane. Which is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. So I think we need to create a new generation of plastics that are true cradle-to-cradle plastics, where they can either be recycled back in the industry or they can be recycled back into nature, composting or whatever. That could move a lot of different plastics. There’s no one single bioplastic that’s going to serve that purpose. Coca-Cola has their plant bottle — this much ballyhooed plant bottle which is made from plant-based plastics. And they’ve come under fire. Because people say, “It’s just like regular PET plastic. It’s not a totally new plastic. It’s not biodegradable.” But to a lot of people, and I kind of agree with them, at least it’s a recyclable plastic. And it fits very easily into a pretty well developed recycling strain. Right now, the technology is ahead of the infrastructure that we need to have support it. Compostable plastics only really make sense if you have a composting infrastructure. And that doesn’t exist in many parts of the country right now.

Frienkel: Which are the hot thing. Everybody who’s got a dog is thinking, “Oh, you know, I should get one of these disposable bags. And those are great if you live in a city which will compost them. Or you put them on your backyard compost. But if you take those compostable dog poop bags and throw them in the trash, and think “at least they won’t last in the landfill forever,” well, you actually don’t want things to biodegrade in the landfill. Because in the atmosphere of the landfill, once something biodegrades, it generates methane. Which is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. So I think we need to create a new generation of plastics that are true cradle-to-cradle plastics, where they can either be recycled back in the industry or they can be recycled back into nature, composting or whatever. That could move a lot of different plastics. There’s no one single bioplastic that’s going to serve that purpose. Coca-Cola has their plant bottle — this much ballyhooed plant bottle which is made from plant-based plastics. And they’ve come under fire. Because people say, “It’s just like regular PET plastic. It’s not a totally new plastic. It’s not biodegradable.” But to a lot of people, and I kind of agree with them, at least it’s a recyclable plastic. And it fits very easily into a pretty well developed recycling strain. Right now, the technology is ahead of the infrastructure that we need to have support it. Compostable plastics only really make sense if you have a composting infrastructure. And that doesn’t exist in many parts of the country right now. Freinkel: If private industry stepped up to the bat, if the makers of polypropylene stepped up to the bat, it would be very helpful. Actually, there’s this private program. Polypropylene is #5 plastics. It’s the stuff used in yogurt containers. It’s a great plastic. It’s a very clean plastic. And there’s a company called Preserve that was founded by this guy in Boston who was disturbed by the fact that it’s almost never recycled. Because there are very few secondary markets. But it’s a very processable plastic. So he started this company and started trying to collect polypropylene and he started off making toothbrushes and trying them in Whole Foods. And it’s since developed into this program where Whole Foods and Stonyfield Yogurt, where they’ve got this program called Gimme 5 that encourages people to bring back yogurt containers that can then be recycled by Preserve. And toothbrushes. And cutlery. As far as I know, that’s mostly a private program in which private businesses step up to the bat. It’s sort of win win for everybody.

Freinkel: If private industry stepped up to the bat, if the makers of polypropylene stepped up to the bat, it would be very helpful. Actually, there’s this private program. Polypropylene is #5 plastics. It’s the stuff used in yogurt containers. It’s a great plastic. It’s a very clean plastic. And there’s a company called Preserve that was founded by this guy in Boston who was disturbed by the fact that it’s almost never recycled. Because there are very few secondary markets. But it’s a very processable plastic. So he started this company and started trying to collect polypropylene and he started off making toothbrushes and trying them in Whole Foods. And it’s since developed into this program where Whole Foods and Stonyfield Yogurt, where they’ve got this program called Gimme 5 that encourages people to bring back yogurt containers that can then be recycled by Preserve. And toothbrushes. And cutlery. As far as I know, that’s mostly a private program in which private businesses step up to the bat. It’s sort of win win for everybody. Correspondent: We’ll have to become farmers. You point out that while experts have discovered some of the chemicals used in IV bags, kitchenware, toys, and furniture fire retardants are harmful, we don’t really know the full health implications of our exposure to all these plastic chemicals. How has this industry been allowed to flourish without considering, “Well, if we’re putting our food or our clothes or our bodies into these plastic environments, maybe we should think about what we’re doing here”? Has oversight mostly been passed on to private industry for this?

Correspondent: We’ll have to become farmers. You point out that while experts have discovered some of the chemicals used in IV bags, kitchenware, toys, and furniture fire retardants are harmful, we don’t really know the full health implications of our exposure to all these plastic chemicals. How has this industry been allowed to flourish without considering, “Well, if we’re putting our food or our clothes or our bodies into these plastic environments, maybe we should think about what we’re doing here”? Has oversight mostly been passed on to private industry for this?