[Table of Contents]

Start at the Beginning: The Daily Seven (Chapter 1)

Previously: The Betrayal (Chapter 5)

The door closed with a sealed shudder and the air gelled to a creepy still. We had only the smooth purr of the town car’s motor and the gentle hiss of the air jockeying for some modal answer to white noise. I tossed my beige bulk onto the plush Corinthian leather seat across from Dottie. I could feel her breathing and beaming, her eyes on me like a lackadaisical meat inspector, but I didn’t want to look at her. I didn’t want to be reminded me that sitting before me was the residue of the woman I had once loved and lost. But I did glance up and I met her eyes and the joy was gone. She was one of those people who walked the earth with a dead sardonic look. But in New Amagaca, that was pretty much all of us.

“Are you here to ruin me again?”

She smiled. A smile that once flowed with natural charm, but that now steered you to look into her eyes even if you were glancing out the window.

“Show some gratitude for a lift, Alex.”

“How did you find me?”

“I was canvassing this sector for a retrofit and my phone blipped. It said you were in the neighborhood.”

“So I’m still bookmarked.”

“Oh, I didn’t bookmark you. That was an accident. But the matrix is automated to remind us of loved ones. Or former loved ones. Reconciliation is prized, although, in your case, I forgot to remove you from my contacts. But I figured that since you were probably still working in Midtown and we were both heading in the same direction…”

“Spare me your charity. You broke my heart.”

She smoothed her hands on her bright golden skirt and shifted upward in her seat.

“Now, Alex, we’re supposed to stick together. That’s the Amagacan way.”

“The way you sold out Sheila. The way you led a status downgrade campaign against me.”

“I could downrank you now if I wanted. Have you thought about that?”

I lowered my head. I looked out the window. We were rolling across what had once been called the Williamsburg Bridge, now christened the Scott Baio Memorial Bridge in honor of his service and sacrifice at the Virginia Massacre. The pedestrian walkways above us were still painted pink. That was one of the few parts of New York they still hadn’t painted over. Several people who couldn’t deal with a life of constant pleasure were leaping to their deaths in the designated suicide zone.

“I was about to call in sick.”

“Now that I would have liked to see. But you got in the car, Alex. It was your choice.” She leaned in. Only a few inches, but it felt like she was right next to me, the very inverse of five years of intimacy. “It was always your choice, Alex. That’s why I had to call the police.”

There was a striped leather portfolio on her lap. The Ruler’s crass insignia — an ankh crammed between the two Chinese symbols for joy — was stitched into the polyurethane.

“For what it’s worth,” she said, “I’m glad you’re still alive.”

“You certainly didn’t make it easy.”

I checked her profile on my phone. Not that I needed to.

“I see you’re a five now,” I said.

“And you’re still toiling in the Abrogation Department?”

“Yeah.”

“How many repeals?”

I was still gazing into the addictive light of my phone even though I didn’t need to, given that I knew that the government only distributed these bright spiffy portfolios to the fives. I guess I needed some statistical confirmation of just how much Dottie had changed. The data provided more comfort than the face in front of me. As a lawyer and now an abrogator, I had always been committed to the evidence. Facts always triangulated between the hurt you were feeling in your heart and the pain you were willing to bear in the future. There was only one conclusion that I could ever form from the supportive material: Dottie had once been the most compassionate soul that I ever knew. She’d stop and buy a sandwich if she ever saw a homeless man. She’d surprise me with dinner if I arrived home late after a long day of writing briefs, just to prove that she wasn’t the only one in our flat who knew how to dazzle in the kitch. We were going to honeymoon in Goa and spend part of our time building shelters in Bihar. Maybe we’d both fallen into that neoliberal middle-class trap of being globetrotting do-gooders. The kind that Thomas Friedman used to extol before he was assassinated during a pubic lecture when he claimed that the Virginia Massacre was just a passing phase of capitalism. They sliced the part of his skin where his mustache rested above his dead lips and the barbarians nailed it to a stick and paraded it along Broadway during the time that the anti-intellectual mobs had formed. When the Great Turnover came, the centrists were the first to surrender their principles to save their own skin, much as they’d severely underestimated the rabid American id that led to all the assassinations. And Dottie had been among the first to change.

“More than I’d care to report. How did you land the five star treatment?”

“I earned it. Just as you climbed back to four.”

“You didn’t help.”

“Sometimes we need to fall down to rise up.”

“Tell that to the folks we just passed on the Baio Bridge.”

“Bootstrap capitalism! It’s not as bad as you think. Here, let me show you something.”

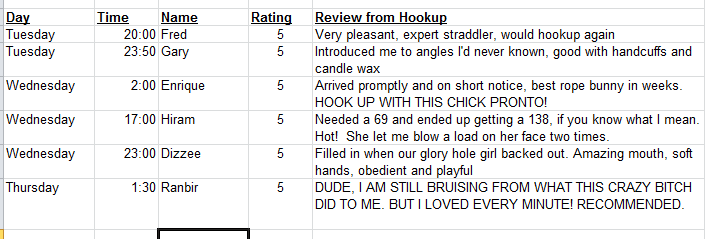

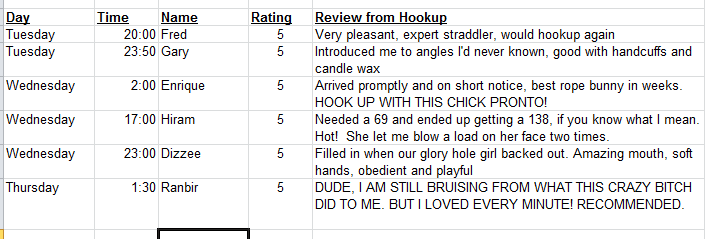

She pulled out a tablet from her portfolio and spun the screen around so I can see the screen. It was an Excel spreadsheet:

You saw many good people shift to such a life, but to see her hookups tabulated like this was too much for me to bear.

“You were always a good data aggregator,” I croaked, fighting back tears. You really couldn’t cry in a climate devoted to pleasure. Crying was forbidden, although you could find a grief hookup if you were careful with the phrases you typed into the search engine.

“Come on, Alex. You asked the question.”

“You didn’t have to do it that way.”

“Are you trying to slut shame me?”

“No. Your life is your life.”

“I’m trying to help!” she said with a freakish enthusiasm. “I was only trying to encourage you! You’re a smart man and you deserve to be a success! I want you to be a five!”

The hell of it was that she really meant this. She really believed that the cold presentation of her dalliances somehow justified her life. It was almost as if she had no memory of the status downgrade. Even the best of us couldn’t always remember the past. We were doomed with the deficiency of our collective memory.

“I’d like to get out of the car.”

“But we’re only ten minutes away. You don’t want to get sick, do you?”

I didn’t, but my stomach was in torrid knots. I was doing everything in my power not to throw up. I didn’t want to fuck anyone after seeing that list. She had known every part of me for five years. We had shared words together that had been burned like the old NYPL catalog. Part of me wondered if my full tabulated essence was memorialized in some way on that tablet.

“Okay,” I said. “Just so long as I’m not cramping your style.”

“Not at all. You know I couldn’t see you when you were a three.”

“You couldn’t love me when the ratings matrix kicked in.”

“Now, Alex, do I have to downvote you? I’m giving you a ride so you can earn your credits! You know we can’t talk about the time before. You’re lucky I didn’t invoke my executive privilege when you started asking your questions. As the Ruler says, ‘Questions are a millstone to progress. Answers are no substitute for pleasure.'”

I was still feeling reckless. Why wasn’t I there with the hopeless cases on the Baio Bridge? Because I had lives to save, that’s why.

“Do you really like being a citizen of New Amagaca?”

“I’m going to pretend I didn’t hear that, Alex, but, yes, it’s been treating me very well.”

“I’m sure.”

“Why can’t you have fun like everybody else? I’ve felt so liberated ever since I changed my focus!”

“What about love?”

“What about love?”

“What about what we had?”

“Alex,” she whispered in a very worried tone. “You know there’s a heavy status fine if you even consider romance.”

“Alright. Romance is dead. Revoked by Ruler decree. So what are you doing these days?”

“They now have me working on the new city grid. Speaking of which…”

She knocked on the window separating us from the driver in the peaked cap.

“Petey?” She turned to me. “You’re near the Citadel, yes?”

“Two blocks away. Near 48th.”

We were stuck in traffic. I was going to be late. The partition slid down.

“Petey, is there any way that we can speed things up?”

“I’m afraid not, Miss Farrell. Bumper to bumper.”

“Oh dear.”

“I’m going to be late.”

She opened her portfolio and took out a military-grade Toughbook. One of those rugged beasts designed to withstand an EMP.

“You’re not going to be late.”

“How?”

“Well, I shouldn’t be telling you this. On the other hand, I could sentence you to death if you spill. So here goes! The Ruler has been developing a new strategic defense grid in every Amagacan city. But we had an infrastructure in place before the Great Turnover. Do you remember the eye in the sky?”

“The elaborate surveillance system that the NYPD had put into effect. They had added audio sensors.”

“It was in the early stages of being weaponized! Watch this!”

I couldn’t really see what she was doing, but, from my vantage point, it looked like she was logging into a shell account. I looked out the window, watching two men paste a new poster of the Ruler onto a fraying billboard.

“This is like that Don DeLillo novel.”

“Don who?”

“Come on. I wasn’t the biggest fan and he wasn’t all that of a favorite. And this wasn’t one of his better novels. Cosmopolis. You remember that one?”

“I don’t know who Don DeLillo is.”

“The only thing missing in this limo is the floor of Carrara marble. And you know damn well who DeLillo is.”

“No, I don’t. Quiet. I’m concentrating.”

I had five minutes to get to the Abrogation Department. There was a chance I could get out and huff it. But as I was considering my plan to be timely, there was a giant rumble outside the car. A gray drone, roughly the size of a storefront, was hovering in the sky outside.

“Aha! It worked!”

“You summoned that?”

“Watch this!”

The drone flew in front of us. I looked ahead and saw that two trucks were tying up traffic.

“Let me check.”

The tapping of keys.

“Nope. Non-essential goods.”

“What do you me….?”

The drone fired a rapid burst of bright purple lasers into the two trucks, targeting the fuel tanks. There was an explosion. The trucks burst into flames. I watched one of the truckers dive out the melting frame of his door, howling at the top of his lungs as the flames charred his body. From one of the spires above us, a sniper locked his rifle on the trucker and put him down with a swift head shot.

“Jesus!”

“Don’t you love new technology? Now let’s see if this works!”

The drone then fired a white spray. The window was cracked and the air around us smelled antiseptic. Some of the cars pulled over, not wishing to be victims of the drone. The spray subsumed the ruined trucks with a fast foam. The drone then hovered above the truck. Two robotic impediments looking like outsize claws designed by a sociopathic MIT genius hopped up on one too many James Cameron movies pushed from the drone, rapidly flattened the truck into scrap metal, and proceeded to lift these resources with it up into the air, where the loud roar dissipated as it flew to who the hell knows where.

Petey put the pedal to the metal.

“It worked!” shrieked Dottie. “We’re going to get you to work on time!”

“You just killed two people.”

“Well, Alex, you’ll probably save two people today when you’re taking in your case load. So it all evens out! I can’t wait until the IT people hear about this.”

What the hell did death mean anymore if everyone was a potential experiment for new tech?

The limo rolled up to my building.

“Dottie, can you do me a favor?”

“Aren’t you going to say thank you?”

“Thank you. I say that only because I have to. Can you do me a favor?”

“Anything for you, four star Alex!”

“If you ever see me wandering around a sector you’re canvassing, please don’t contact me again.”

“Oh.”

“Yes, oh. It was nice knowing you, Dottie.”

I left the limo. I had two minutes to get to my office. As the limo rolled off, I stumbled into the alley where I smoked cigarettes and took deep pulls from my flask after learning that a repeal I had painstakingly tried to make happen did not go through. I threw up, found the polka dot handkerchief already soiled with Grace’s Thursday upset, straightened my tie, and scanned my retina at the security booth for another long day at work.

Next: Elevator Romp (Chapter 7)

10150 / 50000 words. 20% done!