(This is the fourth of a five-part roundtable discussion of Eric Kraft’s Flying. Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Five can be read here.)

Edward Champion writes:

“There was beauty below them, inarguable and unique — many fine things built for the contentment of hardy men — and there was decadence — more ships in bottle than on the water.– but why grieve over this? Looking back at the village we might put ourselves into the shoes of a native son (with a wife and family in Cleveland) coming home for some purpose — a legacy or a set of Hawthorne or a football sweater — and swinging through the streets in good weather what would it matter that the blacksmith shop was now an art school? Our friend from Cleveland might observe, passing through the square at dusk, that this decline or change in spirit had not altered his own humanity and that whatever he was — a man come for a legacy or a drunken sailor looking for a whore — it did not matter whether or not his way was lighted by the twinkling candles in tearooms; it did not change what he was.” — John Cheever, The Wapshot Chronicle

We’ve had many interesting opinions on this book. In favor of Kraft, we have Sarah Weinman, Brian Francis Slattery, Kathleen Maher, Jason Boog, and me. Against Kraft, we have Matt Cheney, Robert Birnbaum; and Dan Green. On the fence (or perhaps on the wing) are Nigel Beale and Anne Fernald.

We’ve had many interesting opinions on this book. In favor of Kraft, we have Sarah Weinman, Brian Francis Slattery, Kathleen Maher, Jason Boog, and me. Against Kraft, we have Matt Cheney, Robert Birnbaum; and Dan Green. On the fence (or perhaps on the wing) are Nigel Beale and Anne Fernald.

Brian has suggested that Kraft is “playing on the same playground as Proust, Nabokov, and several centuries’ worth of other fiction writers and continental philosophers.” And Sarah has evoked Jean Shepherd. But I think Kraft falls somewhere in between. He’s not a full-blown fabulist. But with his libidinous asides and unusual epitaphs and ephemera, I don’t think he can be entirely pinned down as a folk narrative hero (but certainly there is a pining from Peter Leroy to be pinned as a legend). Perhaps a better comparative point is John Cheever (Mr. Birnbaum: I’m sure you’ve read him!), who was neither one nor the other. Much like Cheever’s “The Swimmer” offered a grand fusion between realism and surrealism, with the sense of time attached to the narrative becoming an amorphous expanse. Neddy Merril’s quest begins in a suburb. And perhaps Bolotomy Bay is similar to Cheever’s pool. The headline writer at The New York Times mistakenly declared Cheever “The First Suburbanite” in a recent issue, but such an emphasis clings needlessly to where these stories are set. While Nabokov rather famously declared that he needed to know the lay of the land before writing a narrative, I don’t think these rules apply to Kraft. And with the shifting nature of the characters throughout the Leroy narrative (composites? real or invented?), I don’t think it really matters. My question to the naysayers and the fence-sitters, asked with genuine curiosity, is this: What precisely has prevented you from putting yourself in the shoes of a native son? (And, Matt, I’m not talking about the sentences, but the perspective. While I agree to some degree with Kathleen about the folly of proceeding forward with something you hate, are you so sure that Peter Leroy is so nice? Consider his selfishness. Consider that Albertine is, to a large degree, Peter’s enabler. Consider the prevarications that he is applying to real people. Is playing with the truth so amicable?)

I agree with Brian that Kraft’s jokes would go over well in bars. But I would answer that the bars in question no longer exist in the present. Perhaps they are entirely illusory. Let us consider the DVD that Peter and Albertine discover entitled “Jack and Jennifer’s Dream.” Here is a scenario in which Jack and Jennifer, who run a hotel with a “former-tumbledown-millhouse look,” not only implore our happy couple in the present to enjoy themselves, but present a slim paperback book called “The Story That Is Jack and Jennifer’s.” We are presented with a story detailing how the Yucatan Honeymoon Midnight Snack came to be, and it’s terrible. Mind-numbingly naive. You simply cannot trust it. Kraft then follows this with the DVD found in the room, where the dream becomes a pitch to open a franchise. It’s a sad and hilarious moment. Something that suggests that these nonexistent dreams can now only be communicated through some bizarre entrepreneurship. The desperation contained within this pitch suggests very much that dreams, even terrible and aimless ones, do matter very much. But perhaps these dreams are only attainable through the confines of fiction or Leroy’s “memoirs.” So while Brian may chide our good Marcel for inhabiting his cork-lined room, what’s worse? A tangible set of volumes (a set of Proust in lieu of of a set of Hawthorne) that emerges from this sense of dreaming or unimaginative authorities attempting to rectify or place monetary value on such seemingly aimless drifting?

As to Sarah’s question about earnestness, I’m going to have to disagree with her. And it may be because I had a slightly different reading interpretation than she did. Peter is certainly making a earnest effort (that niceness that Matt mentions) to tell a good yarn, but is he really being all that earnest? The lovely aerocycle may be an amicable chatterbox, but, instead of Peter presenting some of his more negative feelings, the Spirit of Babbington is largely a place for him to kvetch. And Peter betrays the Spirit by leaving her the garage. That particular moment was especially sad and moving for me. Because it represented an emotional transference of what Peter doesn’t have the courage to confess in his memoirs. This imaginary manifestation, who exists in the past almost as a surrogate Albertine (with the stewardess coming in to fill that role later), becomes nothing less than a dumping ground. And that, irrespective of the positive places that Kathleeen brings up, seems to me especially tragic. The idea of dishonoring the wonderful entity that you created in your imagination. Very much like Don Quixote. But unlike Quixote, Peter isn’t really mocked for his efforts. He’s secured an entire subjective realm through his memoirs. But should not some of this be challenged? Should not some of this be mocked? Is it entirely fair to Peter to have him continue like this? Shall we send a case worker over to the Kraft household to ensure that he is treating his creations well?

Maybe this is also where the chapter headings that Jason likes so much come into play. Is it really fair for Peter to label a chapter “THE SECOND MOST REMARKABLE THING IN THE LIFE OF CURTIS BARNSTABLE” when the event in question is really just a replay of the cropdusting scene from North by Northwest? I mean, it’s Peter here who asks Curtis, “Does that sort of thing happen often around here?” “Never,” Curtis replies, “In fact, before that, the most remarkable thing I ever saw around here was you.” As a guy who likes people a lot, I find this especially troubling. Curtis’s two most remarkable things are (a) Peter (a facsimile of the real invented out of whole cloth) and (b) a facsimile of a famous movie scene. Is Peter so self-absorbed that he cannot “remember” what was really great about Curtis? What made him so interesting? What made him a three-dimensional being? Given incidents like this, the ephemera of schematics, magazine ads, and the like becomes more haunting. What right does Peter have to introduce ephemera when his characterizations of the real center first and foremost around him? Or is this the lot of every novelist? I’d be curious to hear what you folks had to say on the subject.

Anne Fernald writes:

I have enjoyed reading and eavesdropping tremendously and have finally more than half the book under my belt. “Taking Off” was slow going indeed, but I am enjoying it more and reading it faster — both seem to help.

Exasperating.

Exasperating would be my one word summary of the Flying trilogy, or what I’ve read of it so far (that would be a bit more than half). I don’t always hate the narrator, Peter Leroy, although I find him cloying. It’s just that the writing is just good enough to make me keep reading and yet, it misses just often enough to make me wonder if my time might be better spent some other way.

For a novel that depends so heavily on boy’s adventure lit, a novel about flying and escape and travel, for a picaresque, these failings are not small.

The successes are not small either. It is really funny and some of the social critique is spot on, some of the observational comedy is genuinely funny. But I don’t find it as funny as Joshua Ferris’ Then We Came to An End, even though this is a much more ambitious, richer, and more allusive book.

Part of the problem is with me: it’s an occupational hazard of my life that I’m reading Kraft’s Flying next to, on the one hand, Ulysses and To the Lighthouse for my teaching, and mountains of the bureaucratic reading of professors (applications, student writing, copyedited book reviews) on the other. Plus, in addition to being in over my head, I am a very, very slow reader and this is a book to gobble. The book is indebted to the big novel of great ambitions without a doubt: it’s full of Shandeisms and Joycean play. But the alternation between memories of the youthful “flight” and the adult reenactment in “On the Wing” rarely arrive at the kind of momentum of the alternation between Mr. Ramsay in the boat and Lily painting at the end of To the Lighthouse — a much more modest journey, but one with tremendous, mythical implications within the book. Time and again, as I page through Ulysses and then return to Flying, I’m struck by how much more Joyce loves Bloom — and makes us love Bloom — than Kraft loves Leroy.

I totally disagree with Sarah’s sense of the heart and mind being widened by the book: I feel myself in the company of a solipsist. I think it’s no coincidence that he has a deep fondness for blowhards, for those loud soliloquists who hang out in bars and diners.

I think Kraft is proud of Leroy and amused by Leroy, I wonder if he is Leroy, but I don’t feel the same intense joyous fondness emanating from Kraft for Leroy nor from me for Leroy.

Sometimes, I even wonder if they are characters to him. It bothers me, for example, that shortly after her release from hospital from a fractured pelvis, Albertine is willing to go along with Peter’s search for a spot to make love en plein air. I’m sorry to be so dogged, but that injury felt really real to me — funny, but also a smart way of showing off their connection, Peter’s failings — and I wanted a line that assured me she was recovered enough for such an adventure. (I know how flat-footed and dumb that sounds, but it broke the illusion for me in ways that were not good.)

Still, there are things that keep me reading and will make me finish the trilogy. I love the trope of the dark-haired woman, always coming on to him, always available, always an anticipation of Albertine; and I love Albertine’s wresting the “truth” of this apparition out of him. In general, I love the intertextual moments where, as Ed promised, the boundaries of memoir and fiction get stretched to their limits. One of the weaknesses of “Taking Off” for me was the lack of such moments of interpretive doubt-casting in the final third or so. I have never read such a funny funny take on the pitiful ways in which small towns try to make their Cheapo Sleepo chain intersections distinct: he has brochure language, of franchises and of unique tourist attractions down pat.

But must there be so many of them? It’s just so damn long. I have a little more patience with it than Dan Green, though if I weren’t reading it for y’all, I think I’d have given up. And then, Sarah’s putting it in the context of the fifties and Kathleen’s elucidation of why Astaire in a blurb is apt was a lot more helpful to me than all the other yammering on about the heavyweights of the history of the novel.

That’s it for now. I am, as Ed suggested, decidedly on the wing.

Nick Antosca writes:

Apologies for weighing in egregiously late, I’m afraid I overestimated my ability to go without sleep for large portions of February. I have only just finished reading, but my delay in getting to this point so was not, as seems to have been the case with others, and others, a result of disinterest or discontent with the book.

My reaction to the first pages was kind of like Matthew’s — uh-oh, the scent of whimsy ahead, and so many pages to go, dear god, the voice and apparent content of this book don’t seem to justify its thickness and weight… but I came around. In the end, I enjoyed it a great deal, even though my experience was fragmented and I probably would have gotten a richer experience by devouring it in a couple sittings, as Sarah (and others?) did.

Flying seems Nabokovian in its playfulness but not in the deftness of its prose, which is extremely clear and easy-to-read but not what might be considered “transcendent” or “transporting” (despite the journey it describes, ha). It’s light and clever and farcicial. And maybe that’s why I kept having the nagging weightiness of content vs. volume of tome issues. That is to say, while I thought the voice was entertaining/amusing/really-well-done, I kept saying to myself, “Does it justify this much? This book is so long!”

One thing that delighted me were the subversions of expectation that happened simultaneously on multiple levels. I particularly liked the moment right near the beginning when Peter’s getting ready to making the aerocycle in the garage and he very unrealistically hopes that all his friends, who’ve begged off, will show up to surprise him with their dedication and support, etc. When he won’t get out of bed yet because he’s “giving his friends time to surprise” him we feel a little pity for him, since we know that it’s a foolish hope; and when he tries to believe they’re assembling outside under his window and convinces himself that the reason he can’t hear them is because “evidently they were a stealthy bunch, those friends of mine,” we’re amused by the extent to which he’s willing to rationalize to avoid acknowledging the fact that his friends don’t want to spend an uncomfortable day abetting his quixotic adventure. But the joke seems to be on us when he goes downstairs… and they’re all there waiting with his father! On immediate further reflection, though, do we believe that they really showed up? Is the appearance of the ready-to-assist mob of friends (and the teacher) just an extension of the delusional expectation that they might show up? If Peter’s willing to delude himself a little bit, why not delude us a lot?

Others have taken issue with the figures and captions. I liked them. I liked the drollery of captioning them with lines taken directly or almost directly from the text as through they were scientific illustrations from a scholarly paper.

I found the brunettes a little eerie, in a very pleasing way–a sort of reverse-Vertigo effect, with the woman who inspires them appearing later and perhaps as a construct or amalgamation — the epitome of the available brunette. What Peter really wants is a perfect foil, so does he conjure one up on the page because she could never exist?

Also, I have to say I’m going to read Flying again — in a sunny place, in a warm time of year. Context is much. It’s a cold and stressful time of year, and simultaneous with this I’ve been reading Brian Evenson novels and Helter Skelter, the Charles Manson book by Vincent Bugliosi, as well as doing readings from my novel that just came out which is about a drowned boy who throws up monster dogs. Flying, I think, didn’t quite fit in, and I had to get into a different mindset every time I picked it up, so I’m honestly very excited to read it again under more salutary conditions.

Matt Cheney writes:

A quick note this time, because much of what I would say has been said quite well by others, most recently Ann and Nick. I’m still inching my way through the book, but my progress is feeling asymptotic at this point, so I doubt I’ll get to the end, but I have certainly developed a better appreciation for the novel(s). My own preferences, proclivities, and prejudices as a reader keep me from being able to embrace Flying with any great enthusiasm, but the responses of the enthusiasts here are certainly helping me expand my appreciation for it.

Ed directed a question toward me that is, I expect, central: “…are you so sure that Peter Leroy is so nice?” He suggests it’s a matter of perspective rather than sentences, and I expect I would agree if I could get past the sentences (by which I mean, I suppose, tone and diction, but the part of me that is revolting against reading the book keeps muttering the word “sentences” in my mind’s ear). Clearly, Leroy possesses many of the qualities of a picaresque rogue, as Jason suggests, and there’s an interesting tension between his presentation of himself and the “reality” that we can guess at beneath the layers of that self presentation.

For some reason, alas, I just can’t draw much energy from that tension in Flying. Though, with Ann, I find Leroy’s narration cloying, that’s not an immediate deal-breaker for me, because cloying narrators can be quite interesting — the problem is what she describes next: “it misses just often enough to make me wonder if my time might be better spent some other way.” Once that wondering begins, I can’t continue, because yes, there are other things I’m reading right now that I’m finding more rewarding.

Nick’s coming around has given me hope, though. If he can make it through Flying while also reading Helter Sketler and Brian Evenson, I’ll keep giving it a shot and hope for more connections.

Nick Antosca writes:

I had trouble with dramatic tension, or lack thereof, too. Somewhere early on, I decided not to hold it against Kraft simply because that wasn’t what he was up to. No fair judging the writer (in most cases) for failing to do what he never tried to do, and so forth. In fairness, I have the same trouble with Pale Fire, a novel I deeply love and respect, which has games aplenty, but which has zero tension or what we might consider dramatic momentum.

Robert Birnbaum writes:

This has been a fine exchange and I especially want to commend the pro Kraftians for their zealous advocacy and scrupulous exegesis.

In one of my conversations with the immensely enjoyable British badboy of letters, Will Self, the subject of his confrontation on a radio program with an English writer of a reactionary bent came up. That writer had a new tome, of which Self, admittedly, had read only a few hundred pages. Self’s adversary took umbrage at Self’s failure to read the book in question in its entirety—to which Self responded, “Did it somehow turn in to War and Peace after two hundred pages?”

On a number of occasions I have arranged to meet an author before I read their current opus — and to my dismay, I found the reading unfruitful. But feeling honor bound to forge ahead, I would — and on occasion I would actually stumble across some kind of code-breaking element and achieve a more felicitous result from my reading. A reward for diligence…

The point, finally, here being what confronts most if not all of us in beginning a new book — what is the fair and respectful threshold of escape for a book with which we are not having a fruitful experience? I ‘d be interested in hearing /reading whether my fellow roundtablers have anything approximating a rule of thumb.

Anne Fernald writes:

In reviewing, I think it’s essential to read the whole thing in order to offer a convincing and fair presentation of just how a book failed or succeeded. If it’s truly awful, I skim. But I cast my eyes on every page.

In a roundtable, like this one, or in broadcast journalism (as in the hilarious but awful Self example), I’m more forgiving of quitting and less thorough skimming.

I felt strongly that I’d just have to beg off this roundtable with an admission of failure unless I finished the first of the trilogy; once that was done, I just kept turning pages: I found that I had some momentum. And I kind of liked it.

If I were the author Self skewered, I’d feel sorely aggrieved: and I think, rightly so. Still, Self’s point, which Kathleen (I think) made earlier with her 100 pages rule of thumb, is right: once you’ve given a work enough of a shake to determine its goals, scope, ambitions, and achievments, it’s ok to bail.

When reading for pleasure, bail at once!

Brian Francis Slattery writes:

I’m sorry to see this discussion go. It’s funny to me that that something as good-natured as Flying should be so divisive. This seems to be further support for Ed’s remark that Kraft isn’t as nice as he seems on the surface; clearly he’s pushing some buttons. Because nobody here has suggested that the book is, you know, stupid. Kraft is a good writer and a smart guy, and it seems that what frustrates people about him is that he never Gets Serious. For instance, why would someone write such a long book that stays so breezy throughout? Aren’t light, comic novels supposed to be short? Why is he screwing with us like this? Even more interesting, those of us who enjoyed the book can’t quite seem to put our fingers on what we like about him. I compared him to Proust and Nabakov, yet as several people have pointed out, the comparison doesn’t really work—which I agree with, but hey, a guy’s got to start somewhere. Then there’s the Hardy Boys/1950s Americana stuff—but that doesn’t cover the games Kraft plays, either.

What I’m saying is that, in some ways, Kraft is something of an original, the sort of guy for whom books by other people only somewhat prepare you to read. He throws together stuff that doesn’t usually get thrown together, and none of us have been quite able to make anything of it. If Kraft were already part of the canon, with imitators and devotees all over the place, we might have the word Kraftian to describe it, because little else would do. Kraft’s doing his own thing, and whether you like it or dislike it, you have to admit that he has a thing he’s doing.

In some ways, Kraft reminds me of John Crowley, another author that some people really like and others find totally maddening. Both set up expectations only to foil them; neither play by rules we’re completely familiar with; both seem to be following a different kind of logic, but refuse to reveal what exactly that logic is—and both seem to like it that way. There’s an interesting second discussion to be had about that, about why we haven’t been able to talk about Flying in the same way that we usually talk about books. Perhaps an interesting critical essay to be written—again, if Kraft were part of the canon, we’d have dozens of such essays—that goes through Kraft’s many novels to pull out the common threads among them and the logic that might weave them all together. I’m not an academic and don’t quite have the mind for that style of reading. But I would love to get a look under the hood of Kraft’s work one of these days, to see how the gears turn.

Robert Birnbaum writes:

I take exception to Brian’s statement “Because nobody here has suggested that the book is, you know, stupid. Kraft is a good writer and a smart guy, and it seems that what frustrates people about him is that he never Gets Serious.”

The fact that Kraft and his effort have not been negatively assessed, I think, stems from a lack of interest. I can’t comment on whether Kraft is smart and a good writer — the first and only threshold has been whether I found him readable — which I did not.

Seeing the author respond to this discussion gave me the possibility that the scales might be removed from my eyes. In short, no go.

Nigel Beale writes:

Somerset Maugham in his introduction to The Ten Best Novels of the World said that the novelist had the right to demand of the reader sufficient imagination, some power of sympathy and “the small amount of application that is needed to read a book of three or four hundred pages.” He also said that a novel is to be read with enjoyment. If it does not give that “it is worthless.”

I wouldn’t say Flying is worthless, however, I’m now twenty pages from the end of “Taking Off,” and still sitting on the runway, not particularly looking forward to the flight. The book, as I mentioned earlier, is amusing enough, but amusing in a TV sitcom sort of way. A few smiles, but a sense that first I could be spending my time much more enjoyably elsewhere; second that the dialogue is inferior to that which I participate in day to day with my more animated, intelligent friends…so why waste the time; why apply myself when I know that rewards are greater elsewhere?

Unless of course, as someone else has said, I’m missing something. Every so often an intriguing concept rears itself in the text, the fallacy of significant coincidence for example: “coincidence is not merely commonplace but constant, a pervasive fact of life and all existence,” which in itself is “ceaseless motion, an uncountable number of events, happening all the time, with an uncountable number of them occurring coincidentally at any moment.” “‘we regard those events as directionless and meaningless until one of them affects us”…we then interpret all events in light of that one that has affected us…

But then this thought, instead of being torn apart, examined, exampled…just sort of drifts off into the fog which hangs over this meandering stream of a story…sure, perhaps the narrative itself is supposed to show and tell and fill out the meanings and themes associated with these big ideas…but if they do, I’m afraid the connections are too loose for me to want to tighten them up myself.

Not sure if I will find the second wind that took Anne to the end of this trilogy.

Megan Sullivan writes:

I’m a late chimer in because I had many problems with this book. Matt’s thoughts echoed mine completely. I made it through the first two sections but have yet to finish the book. Even the obvious set pieces that I know are meant to be funny I don’t find it funny at all. I found a good rhythym at the end of the first section and the beginning of the second, but then it started to drag as the journey progressed. I’m not sure that I have Anne’s fortitude to finish.

I felt Kraft winking at me the entire time I read Flying and that annoyed me. The false cheeriness and throwback language felt flat to me. It’s just not my cup of tea. We can’t all like every book. At least one good thing that came out of reading Flying–this discussion which I’ve been finding very illuminating.

Correspondent: I also wanted to offer an observation. One moment in which Yuka, who is up for Connie, reveals that she was born in Japan. And the production team expresses some concerns because she can’t, in their view, possibly nail the right dialect because she wasn’t born in the States. In fact, Baayork Lee says, “There’s something about being born in America and fighting for a seat on the F train.” Seeing as how Yuka did, in fact, get the part, this is interesting to me. Because if you were to take such a judgment and put it into another occupation, it would be discrimination. So I am curious. If an actor has the chops, should they not be able to essentially get the part irrespective of the background? This is one of the interesting things, I think, about the film, in which you see such a blunt judgment — despite the fact that it’s done in all love — laid down on the table like that. So what of this dilemma?

Correspondent: I also wanted to offer an observation. One moment in which Yuka, who is up for Connie, reveals that she was born in Japan. And the production team expresses some concerns because she can’t, in their view, possibly nail the right dialect because she wasn’t born in the States. In fact, Baayork Lee says, “There’s something about being born in America and fighting for a seat on the F train.” Seeing as how Yuka did, in fact, get the part, this is interesting to me. Because if you were to take such a judgment and put it into another occupation, it would be discrimination. So I am curious. If an actor has the chops, should they not be able to essentially get the part irrespective of the background? This is one of the interesting things, I think, about the film, in which you see such a blunt judgment — despite the fact that it’s done in all love — laid down on the table like that. So what of this dilemma?

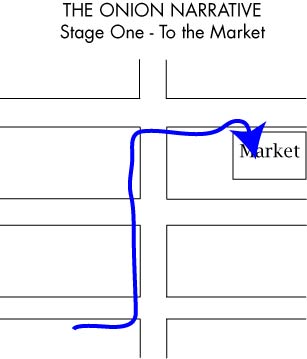

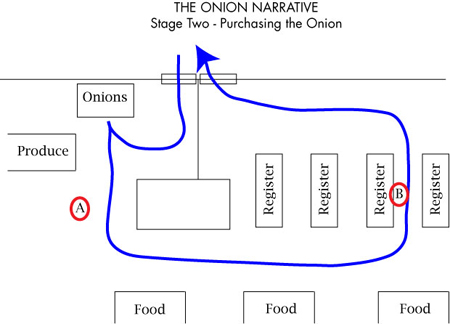

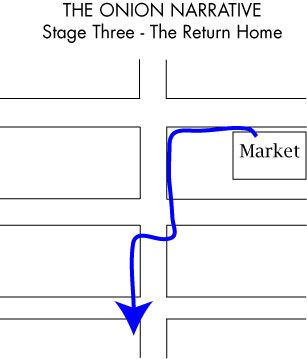

Stage Three of my journey seems less significant than the first two stages. By my own judgment, it is also the least interesting part of the video recreation. The onion has been obtained. I recall that during the original narrative, I found myself observing more people. I was not in a rush to get back. But on the video, I am circling around people rather than approaching them. I do not know if this is because of the camera or because I felt uneasy reproducing the narrative. And why should Stage Three be the least of the three? The primary goal has been obtained. The mind is at ease and can be more spontaneous with the rigid order out of the way. Or so one would think.

Stage Three of my journey seems less significant than the first two stages. By my own judgment, it is also the least interesting part of the video recreation. The onion has been obtained. I recall that during the original narrative, I found myself observing more people. I was not in a rush to get back. But on the video, I am circling around people rather than approaching them. I do not know if this is because of the camera or because I felt uneasy reproducing the narrative. And why should Stage Three be the least of the three? The primary goal has been obtained. The mind is at ease and can be more spontaneous with the rigid order out of the way. Or so one would think.

Boyle: I try to get it both ways. I try to involve you in something in a satiric way. And yet it should also move you. And of course, in this book, I had to do that because of the tragedy of Mamah, which will conclude the book. So you have to set the reader up for that throughout. And I think there is tragedy throughout the book. Tadashi’s life is incredibly tragic in many, many regards. So again, I’m playing one element against the other throughout. And there is commentary upon commentary upon commentary. And, for me, it opened up the structure and it made it fun. It made it invigorating. A lot of the footnotes exist to give you information that I would like you to know about Frank Lloyd Wright and his buildings and where he was at any given time. But a lot of them also, I just express surprise on the part of Tadashi. And I find the hilarious.

Boyle: I try to get it both ways. I try to involve you in something in a satiric way. And yet it should also move you. And of course, in this book, I had to do that because of the tragedy of Mamah, which will conclude the book. So you have to set the reader up for that throughout. And I think there is tragedy throughout the book. Tadashi’s life is incredibly tragic in many, many regards. So again, I’m playing one element against the other throughout. And there is commentary upon commentary upon commentary. And, for me, it opened up the structure and it made it fun. It made it invigorating. A lot of the footnotes exist to give you information that I would like you to know about Frank Lloyd Wright and his buildings and where he was at any given time. But a lot of them also, I just express surprise on the part of Tadashi. And I find the hilarious.

Correspondent: You deem Alec Baldwin a celebutard partly because of the infamous voicemail to his daughter. But I’m wondering if it really is fair, given what you’ve just discussed in relation with Sean Penn and his political sentiments, to take something that was never intended for the public and put it up there with something that is actually in the public record. I mean, is it really fair to deem someone a celebutard for their private actions like this?

Correspondent: You deem Alec Baldwin a celebutard partly because of the infamous voicemail to his daughter. But I’m wondering if it really is fair, given what you’ve just discussed in relation with Sean Penn and his political sentiments, to take something that was never intended for the public and put it up there with something that is actually in the public record. I mean, is it really fair to deem someone a celebutard for their private actions like this?

Correspondent: “This fish is pretty killer.” Well, “killer,” as I understand it, is a recent modifier in the English language.

Correspondent: “This fish is pretty killer.” Well, “killer,” as I understand it, is a recent modifier in the English language.

Correspondent: Has it ever occurred to you to try and make a big score in terms of writing a completely commercial book? In an effort to get people attached into the Peter Leroy universe? Or is such a thing absolutely impossible? Or did you, in fact, try to do this and it turned out to be so quirky and eccentric?

Correspondent: Has it ever occurred to you to try and make a big score in terms of writing a completely commercial book? In an effort to get people attached into the Peter Leroy universe? Or is such a thing absolutely impossible? Or did you, in fact, try to do this and it turned out to be so quirky and eccentric?