It’s a drizzly Tuesday afternoon in the Meatpacking District. I’m waiting outside a hotel suite. It’s just before a junket interview that will be my last. A film publicist wanders in the hallway, jitters in her stride. She’s gabbing into her cell, calmly trying to placate a difficult client who doesn’t realize how difficult he’s being.

Being a journalist, I’m invisible. I’m the barista or bartender of the media system. I’m considered too dimwitted to pay attention to the dismal and terrible things that actors and filmmakers sometimes say. The expectation is that I won’t write about it. The idea here is that I can’t inquire, lest this prevent future interview opportunities from surfacing upon my shoals. I truly don’t care who I talk with, so long as there’s a fun and somewhat enlightening conversation. But this modest goal is incompatible with what is expected. I’m expected to offer softball questions along the lines of “Where do you get your ideas?” or “What’s next?” But I can’t. Just can’t. Don’t have it in me to dumb things down. This simply isn’t what journalists do. I feel compelled to present a film person with a goofy or thoughtful inquiry into his craft. Perhaps it’s naivete. But it worked back in the day for Mike Wallace. But if I do inquire, and I’m just about to, it’s considered “inappropriate.” No explanation or specific solecism given.

Being a journalist, I’m invisible. I’m the barista or bartender of the media system. I’m considered too dimwitted to pay attention to the dismal and terrible things that actors and filmmakers sometimes say. The expectation is that I won’t write about it. The idea here is that I can’t inquire, lest this prevent future interview opportunities from surfacing upon my shoals. I truly don’t care who I talk with, so long as there’s a fun and somewhat enlightening conversation. But this modest goal is incompatible with what is expected. I’m expected to offer softball questions along the lines of “Where do you get your ideas?” or “What’s next?” But I can’t. Just can’t. Don’t have it in me to dumb things down. This simply isn’t what journalists do. I feel compelled to present a film person with a goofy or thoughtful inquiry into his craft. Perhaps it’s naivete. But it worked back in the day for Mike Wallace. But if I do inquire, and I’m just about to, it’s considered “inappropriate.” No explanation or specific solecism given.

I’m expected to be dazzled by the limitless canapes, the endless stream of sandwiches, the food and drink that publicists are expected to provide, the tab paid by a studio with money to burn. But I don’t care about any of this. Because I’m a journalist. Not a freeloader. And I want to do my job.

I don’t know who the client on the phone is, but this publicist has a difficult task on her hands. I learn that the client has had press. Regis, a profile in the Los Angeles Times, and numerous other places. Not bad. But it’s simply not enough. This client wants more.

“I understand,” says the publicist, “but it’s been difficult to get in touch with you. You don’t return my calls. And it would help…”

The publicist is interrupted.

I learn that the publicist has been leaving several voicemails a day. The publicist has been trying to book this client — who could be an egotistical filmmaker or a self-important actor — on several shows. But without that pivotal communication on the client’s end, the all-encompassing media tsunami he demands can’t happen. And even if it can happen, it simply isn’t enough. The publicist is expected to make this happen regardless of the client’s recalcitrance. And in this way, the publicist isn’t all that different from the junket journalist. If an actor detects even the faintest slight, then it’s the journalist who takes the fall and the publicist is chewed out by another publicist just higher up the ladder, but all publicists are equal and just as expendable. The assumption is that the journalist will continue to dun his nose because he needs the high-profile interviews. I, however, don’t need or care to dun my nose. Thanks to a spectacularly bitchy publicist named Betsy Rudnick, a senior account executive at Falco Ink who I haven’t yet met, but who I learn later doesn’t like me but can’t tell me why, I’m about to commit unanticipated hari-kari and I don’t know it.

A film person wants to be on every radio and television show, wants to grace every newspaper. But the film person abdicates all control to the publicist. The film person is expected to be placated, taken care of, have his ego massaged, and who knows what else.

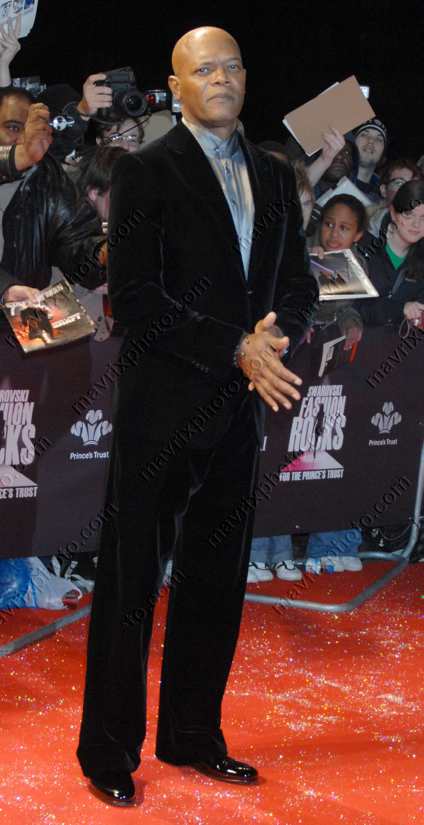

Some New York junket veterans — like a man named Brad Balfour who I have run into at press screenings and interviews and who has eyed my audio equipment not so out of bonhomie or curiosity, but with the hope of discerning some way that he can use me* — boast about having ten minutes with Samuel L. Jackson. I heard Balfour shrieking at the top of his lungs about a Jackson chat at a screening a few months ago. He had bagged Jackson. But what kind of sustained inquiry can you have in ten minutes? In the case of Balfour, the inquiry involves such insipid questions like “What inspired you to do In Country?” and “How did you prepare for this role?” Questions that nearly any junket journalist is going to ask.

Some New York junket veterans — like a man named Brad Balfour who I have run into at press screenings and interviews and who has eyed my audio equipment not so out of bonhomie or curiosity, but with the hope of discerning some way that he can use me* — boast about having ten minutes with Samuel L. Jackson. I heard Balfour shrieking at the top of his lungs about a Jackson chat at a screening a few months ago. He had bagged Jackson. But what kind of sustained inquiry can you have in ten minutes? In the case of Balfour, the inquiry involves such insipid questions like “What inspired you to do In Country?” and “How did you prepare for this role?” Questions that nearly any junket journalist is going to ask.

This take-no-chances approach goes much further. There’s something called a roundtable interview, in which multiple junket journalists band together to offer the same questions with the same answers for the same outlets, where they can then take the same credit for being the “exclusive” interlocutor.

As a result, quotes from the same conversation have a magical way of popping up everywhere. You may think that Balfour got the scoop on Javier Bardem. But wouldn’t you know it? The same quotes — in particular, observe the “How am I with women?” answer and the specific references to Woody Allen and Milos Forman — show up in interviews with Coming Soon’s Edward Douglas, the Boston Globe‘s Michelle Kung, Collider’s Frosty (a nom de plume for a double-dipping journalist?), and the Sunday Mirror. (And if you want to have some real fun, Google a quote. You may be surprised by how frequently a specific phrase appears in interviews. If it doesn’t come from the same conversation, then it’s likely to be a phrase that a film person latches onto. An actor, after all, must know his lines. Boilerplate is an amazing thing.)

This fiction of a perceived exclusive allows readers to think that they’re getting something unique. But when an actor hits New York, “friendly” interviewers are selected to obtain quotes, and the results are nothing less than a mass dissemination of the same material. Junket journalists often team up to collect their work. One group interviews the actor, another a director. The film person maintains the practice of repeating the same quotes, ad nauseum, to these “journalists.” It all becomes a journalistic circlejerk.

The junket has been around longer than you might expect. One of Hollywood’s earliest moments of junket excess came in 1963, when a then whopping $250,000 was spent promoting Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Kramer was summoned to defend the crazed financial excess. It set a precedent. Now nearly every film released by a studio spends a remarkable sum of money on junkets.

And if you think junket journalists are bad, there are other hacks who go much further. The Hollywood Foreign Press Association‘s ignoble relationship with Hollywood has the studios picking up the airfare and hotel bill for journalists. There are sometimes gift bags. Bribery. (For what it’s worth, the HFPA also oversees the Golden Globes, in the event you actually believed that there was some integrity.) And then there’s Ain’t It Cool News’s Harry Knowles, an online “journalist” regularly flown out by studios to premieres. In 2006, Eric D. Snider revealed more, writing a candid column entitled “I Was a Junket Whore,” in which he chronicled further indiscretions. Snider remains banned from Paramount screenings for telling the truth.

I was at Soho House to talk with film people behind Santosh Sivan’s film, Before the Rains. I set up the interview because I had admired Sivan’s 1999 film, The Terrorist, championing it when it had played during the San Francisco Film Festival that year. I had intended to talk with Sivan about his stunning visuals. But the deal was this. I could talk with Sivan, but only if I likewise talked with actors Linus Roache, Jennifer Ehle, Nandita Das, and Rahul Bose. No problem. I set up a roundtable conversation. I figured that questions could be bounced off Sivan and the actors. And all of us would have a fun time. I had set up the interview with an amicable and adept publicist named Caitlin Speed, a lively woman whom I had booked previous interviews with, and who simply got the inquisitive intent and nature of The Bat Segundo Show. But when I showed up, another publicist asked me who I was and who I had set up the interview with. I told her. And eventually, Caitlin and I found each other.

The atmosphere was chaotic. Das was on her way out. Sivan hadn’t arrived. No reason was given. No problem. I’d carry forth an impromptu discussion with the remaining actors. And if Sivan showed up later, he could nudge his way in. This was, after all, the natural flow of conversation.

Actors are, on the whole, very friendly. They are, after all, people. But there are some who have chips on their shoulders the size of Montana. And it is these prima donnas who tarnish the profession. I began my conversation with Bose — easily the best actor in Before the Rains and, as it turned out, the smartest guy at the table — and Ehle, given a relatively thankless role as the wife to Roache’s adulterer. Things started off okay, with Bose claiming to be Ehle and “very sexy.” But when Roache, the film’s leading man, arrived, flashing his pearly whites, I was expected to break off my conversation with Bose to acknowledge his presence. (You can hear this awkward pause in the podcast. I’m presenting the audio file below unedited. I leave others to make up their minds over whether I went over the line with my questions or whether the actors I talked with were incapable of working without a script.) The problem was that I was in the middle of a query with Bose on how Sivan had placed his character at the top of a cliff, and I was curious to know how landscape and position affected his performance. And I thought it very rude to break off this conversation in media res. When Bose was finished with his answer, I then introduced Roache. Roache was getting fidgety, presumably because he was not the center of attention.

Actors are, on the whole, very friendly. They are, after all, people. But there are some who have chips on their shoulders the size of Montana. And it is these prima donnas who tarnish the profession. I began my conversation with Bose — easily the best actor in Before the Rains and, as it turned out, the smartest guy at the table — and Ehle, given a relatively thankless role as the wife to Roache’s adulterer. Things started off okay, with Bose claiming to be Ehle and “very sexy.” But when Roache, the film’s leading man, arrived, flashing his pearly whites, I was expected to break off my conversation with Bose to acknowledge his presence. (You can hear this awkward pause in the podcast. I’m presenting the audio file below unedited. I leave others to make up their minds over whether I went over the line with my questions or whether the actors I talked with were incapable of working without a script.) The problem was that I was in the middle of a query with Bose on how Sivan had placed his character at the top of a cliff, and I was curious to know how landscape and position affected his performance. And I thought it very rude to break off this conversation in media res. When Bose was finished with his answer, I then introduced Roache. Roache was getting fidgety, presumably because he was not the center of attention.

Me: I should point out that Linus Roache has just joined us. How are you doing?

Roache: I’m very good. How are you?

Me: Doing fantastic. I alluded to — I was talking with Jennifer about the scene with you and Jennifer in the bedroom, where both of you are positioned in a manner in which — you’re both diagonal to the bed frame. We were talking about this notion of performance in relation to landscape. And I was wondering if you had any particular thoughts on how landscape or the environment in this film — because this is a very environment-specific film — pertains to your performance. Or working within these limitations.

Roache: Wow! What a question.

Ehle: I didn’t talk about that at all. Ed was talking about that. I said I had no idea about the landscape or anything.

Roache: I don’t know how to answer that. Uh….

Bose: I did the mountains. Landscape and the mountains were mine. She said she did the tea gardens.

Ehle: Yeah.

There was nervous laughter. And at this point, Roache then shifted into boilerplate.

Roache: I don’t know. I just loved being there. I was just out of my mind being there. It was just such an incredible environment to make a movie in. I literally like — I had tears in my eyes when I left. Because I had never been in such beauty for so long. So I understand why my character didn’t want to leave there. The way he fell in love with it. So.

Okay. So he wasn’t getting it. So I thought I’d try a goofier approach to loosen Roache up. Something predicated upon an observation I had of the film, something I was curious about, and something he might have some fun with.

Me: There was one aspect to your character that actually disturbed me. And that was the fact that your hair does not move — with an exception near the end. There’s a stray follicle that actually sticks out. But for the most part, your hair is completely slicked back.

There was a confused look on Roache’s face. Bose tried to bail him out.

Bose: He was very particular about it. Linus, you know, I won’t say he’s vain. But there’s definitely a hair thing going on there. And he just — if his hair would move, he would call for a cut and take the shot again. He said, “Let me know if my hair ever moves.”

Me: No, but I mean was this an actual plan on your part? Because not even the wind can knock your hair out of place.

Ehle: Did you enjoy the movie?

Me: No, serious! It was like a Steven Seagal motif or something.

Roache: I never noticed that. I’ve got scenes where I’m covered in water. And I’ve got scenes where my hair’s all over the place.

Me: Even…really? Because every single time, your hair is like completely pomaded.

Roache: Well, they did use pomade in 1939. But yeah.

Me: Well was there any particular Brylcreem thing?

Roache: Yeah, we used hair pomade that they used in 1937.

Me: What research did you do to get the exact nature of Brylcreem right?

Roache remained baffled. He glared at Bose, annoyed that Bose, a mere supporting actor, was the better wit.

The hair angle seemed right at the time. Knowing of the mothballs that Marlon Brando had placed into his mouth for Don Corleone, I was genuinely curious about the question of how slicking back one’s hair affected an actor’s performance. But I also wanted to have fun with this. And I can now see how an oversensitive “Serious Actor” might take the Steven Seagal comparison the wrong way. It is worth observing that Roache’s Gaia Community profile page has “to help define human relationship beyond ego” listed as his singular Goal.

I then asked a question to the group about how Sivan’s color schemes — green devoted to the colonialists, brown devoted to the tribes, and red foreshadowing a tragic event — might have affected performance. I wanted these three actors to understand that this was an inquiry. Roache then burst in with an answer.

Roache: This movie was more about a kind of creative, you know, rock and roll, jazz fusion situation. Because you had a creative genius like Santosh Sivan. I mean, there weren’t a lot of huge decisions being made in this kind of arty level like that. It was more like a creative process that was unfolding. And some of it was crazy and chaotic. And some of it was just like following what was there and making the most of it. And that’s what a genius like Santosh does. So…

Me: Yeah, but I…

Ehle: If there was anything intellectual about the film, it was streaming out of Santosh. I don’t think anybody ever sat down. It was a very unconstipated process.

In other words, any interview was a matter of parroting the press notes. Any remotely intellectual query was “constipated” and verboten.

Roache: Yeah, yeah. The script though was well thought through and multi-layered. In terms of taking a domestic story, extrapolating that out into something epic. So that’s why you had structure. That’s where you had structure. But within that, you had this guy who was like, “No no no, that shot isn’t about you. It’s about an insect.”

Me: Yeah. Well, landscape is very important. In your house, in your character’s house, there is this particular color scheme going on. So as a result, this has to affect your performance on some level. There’s the red carpet. The red that’s kind of a foreshadowing of what’s going to happen later on in the particular film. And so when you are dealing with colors that are this dominant on the set, and in your particular environment, this has to have some effect upon your performance.

Roache was having none of this. And so I brought up the way in which his eyebrows had moved up and down as the events unfolded in the film. Roache mentioned something about training at the “eyebrow school” and was then ushered away from the table.

The conversation continued with Bose and Ehle, and there were a few interesting thoughts exchanged about acting with gesture limitations. But the mood had permanently altered. I had committed the unpardonable crime of “going after” the leading man. When the actors left the table, they used a common status exercise to turn their backs to me and not offer me any kind of eye contact. Ironically enough, I had brought up the question of eye contact during the course of the interview.

My friend, serving as a technical assistant, and I left the room to ponder what had just happened. She had helped me out with a few other multiple person interviews. And she had observed another actor run away after I had asked a question about the relationship between backstory and performance. This interview, she told me, had outdone that.

We then returned to the white room for my turn to talk with Sivan. I had been told by Caitlin that I would get five minutes. Another woman — the aforementioned bitchy publicist, Betsy Rudnick, as it turned out — then told me that there was “no time in his schedule.” I told her that I only needed five minutes and that I had prepared specific questions, that one of the reasons I had come was to talk with Sivan. But talking with Sivan was impossible. A phoner was offered. My friend, who was utterly appalled by the way I was being treated, then said, “We don’t do phoners….ever.” I then tried to smooth things over by asking how long Sivan was in town for, suggesting that I could come back the next day to conduct the interview. Perhaps we could make more of this and have a serious conversation about the film. Rudnick retreated away.

We waited some more. I observed Rudnick laying into Caitlin, who stood shell-shocked by the window. I approached Caitlin and asked what the problem was. She said, “I don’t understand. The guys from The Signal loved you. So did the Hennegan brothers.”

I then approached Rudnick and asked again what the deal was with Sivan.

Rudnick snapped at me, telling me that there would now be no interview with Sivan. The reasons and conditions were changing by the minute. She told me that I had made the actors uncomfortable. That my questions were “inappropriate.”

“What specific questions?” I asked.

She would not say. So we left without causing a stink.

Out in the streets, I was overcome with rage. Not for the unprofessional manner in which Rudnick had handled the Sivan interview, but because I then fully understood how the junket system was a sham. I was upset by the manner in which Rudnick had said something terrible to Caitlin, who is a good person, and how all this had presumably originated from a minor affront to Linus Roache’s ego. He seriously believed that he could coast by on his generic answers. He seriously expected to be the center of attention.

I felt compelled to smoke a rare cigarette.

I resolved then and there never to do a junket interview again. And, at least for the time being, I do not want to talk with actors. I will have nothing to do with Falco Ink or any agency that Betsy Rudnick is a part of. I am not interested in being a marketing tool. I’m interested in inquiry. I’m interested in maintaining the mix of goofy and intellectual questions that have long been at the center of The Bat Segundo Show.

Again, I leave the listeners to judge whether my questions were “inappropriate.” The audio can be listened to at the end of this post. Yes, there were some tangents involving Roache’s hair and the way that he used his eyebrows. I suppose that what makes my conversation different from, say, David Letterman interviewing Gwyneth Paltrow about her knee is that I opted not to stare in awe at Roache’s middle-aged mien or worship his almighty presence, whereas Letterman’s intent involved soothing Paltrow. And it says something that James Lipton, the man considered by many to be the finest actor-oriented interviewer, often has actors spill their guts out to him on personal matters — most notably, Jack Lemmon confessing his alcoholism. Curtis White has identified this tendency to prioritize the personal over the intellectual as symptomatic of the Middle Mind, represented by interviewers like Terry Gross. Citing an author whose real-life husband had dropped dead shortly before this author’s book was published, White observed that “[t]his was the point at which the book became interesting for Terry. If her poor husband hadn’t dropped dead, Terry would never have been interested in her or her book for this ‘show of shows.’ ‘What did it feel like to suspect you’d killed your own husband with your art?’ Fresh Air? How about Lurid Speculations? It’s like Dr. Laura for people with bachelor’s degrees. Car Talk has more intellectual content.”

The “inappropriateness” was the idea that aspects of an actor’s performance were open to playful or even quasi-intellectual questioning, and that this served in sharp contrast to the lurid soothing and constant ego-stroking that today’s celebrity interviews require. It wasn’t as if I had asked Roache what his favorite sexual position was. Although I suppose that this question would have been more “appropriate” than trying to query Roache about his acting process.

But if a film journalist does not play the fool, if he asks an actor to use his brain, or if does not spend his time assuaging the actor in some way, it is a contumely to the control that the film industry wishes to maintain. Any trade secrets or insights for the public are reserved for the DVD commentaries, which generate more money for both the studios and the paid participants. And the Betsy Rudnicks of our world demand a climate in which journalists are supplicant sycophants, but the perception of inquiry is sustained because the interview is framed in a Q&A format predetermined by unreasonable conditions and unvoiced demands. The film journalism world is as phony and fabricated as the film world. And from these execrable conditions, self-serving hacks like Brad Balfour boast and profit.

These people believe that you are stupid. They believe that you will buy anything they tell you to. And as the film industry has extended its control over the types of questions and the types of journalists that actors and directors will talk with, the only spirit of resistance comes from celebrity gossip reporters determined to dig up any bit of nastiness. And the public, hoping for one small shred of the truth, laps this up. But despite this, the pursuit for intellectual truth is abandoned.

Because of this, I have decided to abandon my brief flirtation with film journalism. I’m sticking with books, comics, and a few other things. When I wrote about movies in the late ’90’s, there was still the possibility of conducting interviews with inquiry in mind. But that time has now passed. Conversation has been replaced by kissing an actor’s ass. Current film coverage, given what I have described above, is not in any true sense journalistic. It also isn’t much fun. The true sign that it’s over is that opportunist typists like Brad Balfour seriously believe that they are journalists, and they do not recognize the sad solipsistic leeches staring back in the mirror.

* — Balfour does indeed use people, such as this poor guy who was “[e]ager enough to get sucked into becoming a transcriber for Mr. Balfour: transcribing many of his interviews for eventual publication on the website.”

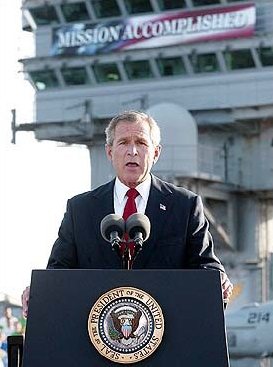

Others will likely perceive this film to be mostly about the visuals atop the visuals, the analysis atop the analysis, the meta within the meta. But the real “standard operating procedure” explored in this film isn’t so much the pedestrian issue of how war caused the lines of basic human decency to become fuzzy, but the manner in which a great filmmaker has partially abandoned his subtleties to get Americans hopping mad. The faults lie not in the filmmakers and not, as White suggests, the critics. They’re doing their best to continue the dialogue, but their efforts have increasingly fallen upon deaf ears. For Abu Ghraib does not entertain. And neither does moral outrage.

Others will likely perceive this film to be mostly about the visuals atop the visuals, the analysis atop the analysis, the meta within the meta. But the real “standard operating procedure” explored in this film isn’t so much the pedestrian issue of how war caused the lines of basic human decency to become fuzzy, but the manner in which a great filmmaker has partially abandoned his subtleties to get Americans hopping mad. The faults lie not in the filmmakers and not, as White suggests, the critics. They’re doing their best to continue the dialogue, but their efforts have increasingly fallen upon deaf ears. For Abu Ghraib does not entertain. And neither does moral outrage.

Brown: Well, it’s something. And I haven’t entirely figured out why. I mean, there’s something about when you know it’s true. There’s something about that honesty, that authenticity, that kind of heightens the impact of things sometimes. Which is why I’ve avoided doing more fictionalized autobiography. And sometimes I’ve thought about moving in that direction. And then it just doesn’t feel right for what I’ve done so far. But on the other hand, books — like some of the Bighead stuff — there are some very personal autobiographical elements sort of in there. So in a way, I kinda do it occasionally. In various half-assed ways.

Brown: Well, it’s something. And I haven’t entirely figured out why. I mean, there’s something about when you know it’s true. There’s something about that honesty, that authenticity, that kind of heightens the impact of things sometimes. Which is why I’ve avoided doing more fictionalized autobiography. And sometimes I’ve thought about moving in that direction. And then it just doesn’t feel right for what I’ve done so far. But on the other hand, books — like some of the Bighead stuff — there are some very personal autobiographical elements sort of in there. So in a way, I kinda do it occasionally. In various half-assed ways.

There’s a scene at the end of the first issue of Secret Invasion in which duplicates of many Marvel characters dressed as they appeared in the seventies show up. I asked Quesada if there was any worry about cognitive dissonance with all the characters in seventies’ clothing. Because in the Marvel Universe continuity, none of them are old enough to have been around in the seventies. The extreme example of this is Luke Cage—Power Man—walking around with a giant afro and a tiara on his head. He said, “Yeah, Power Man had that tiara and it was six years ago [in Marvel continuity], he was just having a real fashion problem then. You know, that’s the least of the problems with the Marvel Universe. Every story practically contradicts other stories because we’re coming out with so many of them all the time. That’s what a lot of people don’t understand. You can’t get caught up in these things.” And then he leaned in conspiratorially, “I’ll tell you something about comics. We just make this shit up. Every day we go in there and just make this shit up.”

There’s a scene at the end of the first issue of Secret Invasion in which duplicates of many Marvel characters dressed as they appeared in the seventies show up. I asked Quesada if there was any worry about cognitive dissonance with all the characters in seventies’ clothing. Because in the Marvel Universe continuity, none of them are old enough to have been around in the seventies. The extreme example of this is Luke Cage—Power Man—walking around with a giant afro and a tiara on his head. He said, “Yeah, Power Man had that tiara and it was six years ago [in Marvel continuity], he was just having a real fashion problem then. You know, that’s the least of the problems with the Marvel Universe. Every story practically contradicts other stories because we’re coming out with so many of them all the time. That’s what a lot of people don’t understand. You can’t get caught up in these things.” And then he leaned in conspiratorially, “I’ll tell you something about comics. We just make this shit up. Every day we go in there and just make this shit up.” Correspondent: Anna is actually a palindrome. Is that intentional?

Correspondent: Anna is actually a palindrome. Is that intentional?

I listened to Kipen talk. He described his apparent frustration with the San Francisco Chronicle failing to hire another full-time book critic to replace him, conveying the reality of newspaper book sections facing serious cuts, and suggesting that the Big Read campaign was intended as a partial answer to the

I listened to Kipen talk. He described his apparent frustration with the San Francisco Chronicle failing to hire another full-time book critic to replace him, conveying the reality of newspaper book sections facing serious cuts, and suggesting that the Big Read campaign was intended as a partial answer to the  (To give you a sense of how little this idea would cost, $104,000 could pay for five reviews a week, 52 weeks a year, with each writer paid $400 per piece. Given this math, I’m wondered how much it had cost Kipen to rent out the Commerce Building and to pay for hotels, flights, food and drink. $10,000 maybe? Kill ten social functions along these lines and give the money to writers.)

(To give you a sense of how little this idea would cost, $104,000 could pay for five reviews a week, 52 weeks a year, with each writer paid $400 per piece. Given this math, I’m wondered how much it had cost Kipen to rent out the Commerce Building and to pay for hotels, flights, food and drink. $10,000 maybe? Kill ten social functions along these lines and give the money to writers.)

The music, however, seemed to be dying. The actual old-timers, the ones who had taught the hippies how to do it in the 1970s, were actually dying, one after the other. On my first visit to a festival down south in 1997, I seemed to be one of about five musicians under the age of thirty. Old-time music had seen a big comeback with the folk revival—people my parents’ age—but from where I stood, it seemed like that might be the end of it, for reasons I couldn’t fathom.

The music, however, seemed to be dying. The actual old-timers, the ones who had taught the hippies how to do it in the 1970s, were actually dying, one after the other. On my first visit to a festival down south in 1997, I seemed to be one of about five musicians under the age of thirty. Old-time music had seen a big comeback with the folk revival—people my parents’ age—but from where I stood, it seemed like that might be the end of it, for reasons I couldn’t fathom.

This film may be something of a gamble for Wong Kar-Wai, but the die is miscast. You simply don’t hire a hunky leading man like Jude Law to be a cafe proprietor. Not if you care about verisimilitude. Law is as flagrant as John Wayne’s Roman centurion supervising Christ’s execution in The Greatest Story Ever Told. The good people who work in the service sector remain largely anonymous, and it would have behooved Wong Kar-Wai to settle for a more interesting character actor in this part. And you don’t hire a doe-eyed cipher like Norah Jones to play a character who has no goal in life other than to work all the time and wander aimlessly around the States. Let me put it to you this way: The paint currently peeling outside my window has more personality than Norah Jones’s execrable Elizabeth, who learns nothing from being mugged on a subway or being dumped by her main man.

This film may be something of a gamble for Wong Kar-Wai, but the die is miscast. You simply don’t hire a hunky leading man like Jude Law to be a cafe proprietor. Not if you care about verisimilitude. Law is as flagrant as John Wayne’s Roman centurion supervising Christ’s execution in The Greatest Story Ever Told. The good people who work in the service sector remain largely anonymous, and it would have behooved Wong Kar-Wai to settle for a more interesting character actor in this part. And you don’t hire a doe-eyed cipher like Norah Jones to play a character who has no goal in life other than to work all the time and wander aimlessly around the States. Let me put it to you this way: The paint currently peeling outside my window has more personality than Norah Jones’s execrable Elizabeth, who learns nothing from being mugged on a subway or being dumped by her main man.  I should also observe that Darius Khondji’s cinematography is taken with doors. There are conversations in doors. A PULL sign on the door of a Memphis bar gets prominent coverage. If My Blueberry Nights doesn’t work as Food Network counterprogramming, then it will certainly excite any JELD-WEN employee who remains convinced that his hard work is a thankless job.

I should also observe that Darius Khondji’s cinematography is taken with doors. There are conversations in doors. A PULL sign on the door of a Memphis bar gets prominent coverage. If My Blueberry Nights doesn’t work as Food Network counterprogramming, then it will certainly excite any JELD-WEN employee who remains convinced that his hard work is a thankless job.

National Book Award-winning writer William T. Vollmann stunned the Penguin offices when he submitted a 22-page children’s book to Viking editor Paul Slovak this morning.

National Book Award-winning writer William T. Vollmann stunned the Penguin offices when he submitted a 22-page children’s book to Viking editor Paul Slovak this morning.