My 75 Books post for the past two weeks will still have to wait, but in the meantime, one of the books, Elliot Perlman’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, has been taken up by the remarkable Jenny D. Her verdict: She completely loved it. Again, we have a possible case here of Perlman being misunderstood. But there are easy reasons to love and there are easy reasons to hate the book. I’ll say that I thought Simon, much like all the other cases, an inveterate whiner, and yet an interesting one. I think the biggest point of contention is this: If Simon is an intellectual, why does he not rationalize his way out of loving/stalking Anna, much less kidnapping her son? If you can accept this wild melodramatic premise, then I think you will accept the book. My theory for those who love it and those who hate it: If during some portion of your life you have thought or have been momentarily misguided by such visceral flights, you will “get” it. Perhaps in Australia, where the book was a bestseller, this is more of an unreserved character trait than in lofty New York circles. Then again, reader temperament shouldn’t be a criteria for whether a book is “good” or not.

Month / February 2006

The Bat Segundo Show #22

Authors: Megan Sullivan, Rupert Thomson, Scott Esposito and Edward Falco.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Looking for answers in British science fiction.

Subjects Discussed: How the idea came about, relentlessly cheery Swedish girlfriends, how Rupert Thomson processes his prodigious research, Ian McEwan, inspiration vs. craft, the trappings of being a “speculative fiction writer,” entertaining novels vs. literary novels, the difficulties of first-person narration, George Orwell, Anthony Burgess’ The Wanting Seed, Mikhail Bulgakov and literary influences, definitive grit in rural settings, disturbing characters, sex and death, decorum in fiction, what’s not talked about in fiction, manhood vs. multicultralism, Catholicism, the influence of personal background, Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, World War II, realism vs. postmodernism, hypertext fiction, compulsions, experimental fiction, literary vs. commercial fiction, and writing in longhand vs. writing on computer.

The Bat Segundo Show #21

Authors: Sam Jones, Ander Monson, C. Max Magee and Elizabeth Crane.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Snubbed and self-righteous.

Subjects Discussed: Visceral voice vs. conceptual voice, the book’s origins, the Monson universe of stories, snow, self-help books, postmodernism, the war on ambitious fiction, John Barth, the original expansive form of Other Electricities, Twin Peaks, book design, Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves, experimental fiction, how Other Electricities was almost published by McSweeney’s Books, Rick Moody, Monson’s obsession with snow, mashed potatoes, Jonas Hanway, umbrellas, comparisons with Elizabeth McKenzie’s Stop that Girl, writers named Elizabeth, blatant autobiographical fiction vs. entirely invented fiction, Owen Wilson, the influence of pop culture upon Crane’s writing, numerology, three-minute films, Maury Povich’s sadism, writing for Nerve, the horrors of blueberry bagels, the influence of David Foster Wallce, Michiko Kakutani, the credibility of “by the way” in dialogue, being categorized as chicklit, dicklit, Nick Laird, on being reviewed, the pros and cons of being a woman writer, and New York vs. Chicago.

A Map to the Music of Time

One person’s history of music, as represented on a London Underground map. (PDF)

Questions for Rupert Thomson

This week, at the LBC, Rupert Thomson Week begins. The author himself will be on deck tomorrow (12:30 PM-2:00 PM PST, 3:30 PM-5:00 PM EST) to answer questions from readers pertaining to Divided Kingdom. Feel free to leave a comment in this thread if you have a specific question.

To Buy a Vowell

Keelin McDonnell’s New Republic essay, “The Case Against Sarah Vowell”, would be completely worthless, had he not raised the perfectly valid point that Vowell is unable to convey political events with any sophistication.

Vowell’s recent New York Times columns represent yet another move in the ongoing political commentary shift from serious thinkers to humorists like Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert and, of course, Vowell. Taken as humor pieces, this trio’s collective contributions certainly represent entertaining diversions. There would be nothing wrong with this, provided that those who watch The Daily Show or who listen to This American Life actually understood that what they were watching was entertainment, rather than deep political thought. But it seems clear to me that more people are willing to take The Daily Show‘s “news” as gospel because it entertains them or perhaps because the current television news outlets simply cannot offer a perspective outside of the martial, tickertape headine and multiple windows model.

As intellectual material, however, the collective oeuvre of Stewart, Colbert and Vowell can be categorized somewhere between some high schooler gushing over a dogeared copy of Atlas Shrugged and a starry-eyed undergraduate who believes that Chomsky is God.

Take, for example, Vowell’s February 5 column, “Gimme Torture,” in which the subject of torture is conveyed through the prism of Kiefer Sutherland’s Jack Bauer on 24. Rather than examining how the troubling notion of Bauer, a Dirty Harry-like character who throws the Constitution and due process out the window on a weekly (i.e., hourly) basis, might just be a tad pernicious in getting 24‘s many viewers to remember basic civics (without even mentioning a pro-Patriot Act commercial which aired during the episode Vowell describes), Vowell offers the banal conclusion that she’s “a little less gulty” ordering a DVD set of 24. The essay is certainly amusing, but Vowell eschews using her comic gifts to point out how the show’s tone, much less the commercial, might influence some viewers to feel a little less bad about sacrificing civil liberties.

Perhaps the problem here is that political essays in America are, for the most part, fairly predictable affairs, whether they come from left or right. We all get on the same soapboxes. And inevitably, we all pluck the same unsubtle chords.

To address Bernard Henri-Levy’s recent concerns, I really don’t think that the Left is asleep, nor do I believe that the political essay is necessarily dead. But I do think that the shift to humorists or novelists offering “political writing” for their newspapers — even the half-baked “political fiction” to be found in Stephen Elliott’s Politically Inspired, which is more of an exercise in deferring serious thinking by exploring such predictable associations as a story of Bush in the guise of a Minnesota schoolboy — is counterproductive, if not destructive, to real discourse.

The problem is that when one writes a political essay these days, one is expected to adhere to a predisposed thinking pattern. The American Left, in particular, being so fragile and regularly maimed by its lack of mobilization, risks offending its peers, much less specific groups. One is expected these days to assume that a reading audience will agree with everything you state, rather than questioning another person’s points, much less one’s own, in a civil manner. And for all the tyrannies of the Bush administration, how tyrannical is this kind of groupthink?

I had hoped to talk to Vowell about these issues when she rolled through town, but her very friendly publicist explained to me that these Times pieces were keeping her quite busy. Perhaps the explanation here is that Vowell is working with harder deadlines than she was accustomed to. But I don’t think so. I think the New York Times has set the bar considerably lower than the Baltimore Herald Tribune or the Baltimore Sun ever did for H.L. Mencken. Because today’s m.o. is to entertain. And coming to grips with the sober realities of torture, political corruption and the venal actions of politicians, left or right, seems incompatible with this apparent necessity.

(via Chekhov’s Mistress)

Send Help

The Kills’ “Dead Road 7” is stuck in my head. And now I know, all too painfully, how ridiculous the lyrics are. Any remedies are welcome.

Why Can’t the Nutballs Go After Uwe Boll Instead?

Country Don’t Mean Dumb, Ebert

I haven’t seen Firewall and have no intention to. This is not because I am a film snob (I am) or that I am averse to seeing a popcorn thriller (with enough friends, drinks and/or heavy petting, yes). It’s simply because I saw Firewall the last time it came around — when it was called Air Force One.

However, I must question Roger Ebert’s review, which offers a remarkably unsophisticated argument that is both anti-cultural and anti-intellectual.

Ebert writes:

But there is a larger question: Need a thriller be plausible in order to be entertaining? One of the most common routines in the filmcrit biz, one I have myself performed many times, involves demolishing the credibility of a plot as if you have therefore demolished the movie. I think there’s a sliding scale involved: If the movie is manifestly impossible while you’re watching it, then that can be fatal (unless, of course, it is a movie intended to be manifestly impossible, like a James Bond thriller). If however, the movie holds water or at least doesn’t leak too quickly, I’m not very concerned about whether you can tear it to pieces after you leave the theater.

There is no larger question here. A lousy thriller might be entertaining in a base or déclassé sense if one cannot buy the character motivations, much less the reality of the world portrayed. But should we prop up such a lead balloon as high art? Should a thriller motivated by cardboard characters, formulaic conventions, derivative banter and baseless logic be given a three-star review? If one has any love for culture at all, I should say not.

Ebert has, throughout his career, positioned himself as a populist critic. Had it not been for Ebert, countless smaller films, made with thought, care and a concern for the real, might never have seen the light of day, much less garnered attention on the film festival criticuits.

But if Ebert’s purpose is to educate or inform the public about film through the clear and thoughtful voice one finds in his reviews, his Overlooked Film Festival and his handy Little Movie Glossary, then it seems to me that the critical standards he champions should apply across the board. Rewarding Hollywood for insulting its audience with yet another overhyped and jejune thriller is both a disservice to Ebert’s work as a critic and a disservice to Ebert’s readers.

Granted, as Susan Sontag has pointed out, camp can be appreciated under certain conditions. But I suspect Firewall is not that form of camp. A film without nuance or even a half-assed wisdom can’t really be qualified. The fact is that there’s no real distinction or playfulness in seeing Harrison Ford barking “I want my family back!” for the umpteenth time. It is an image as rote and repeated as an exploding car. It is worse than a trope. It is a redundancy. (By comparison, take a bottom-of-the-barrel film like Cabin Fever. It is dumb yet enjoyable camp. You have to give writer-director Eli Roth some points in Cabin Fever for sending up the silly “Let’s party!” feel of 1980s slasher movies with the backwoods deputy character or playing off of discomfort with the infamous leg shaving scene. The point is, like Cabin Fever or not, there is a clear effort on Roth’s part to attempt something distinct.)

To dignify or to give credence to a film such as Firewall or Flight Plan (a terrible movie with Jodie Foster, which I have seen) simply because it has a Major Star is to handicap a failed serious attempt without any cultural qualifier. It does not follow that the cinematic presence of Foster or Ford alone contributes exclusively to artistic quality, and yet even Ebert gives it a fair pass as he points out that Ford “needs to be in better condition than a 20-year-old triathlon champion” during Firewall‘s final scenes. This remarkable critical position rewards bonehead filmmakers who string together absurd plot holes and have the arrogance to expect audiences to be thrilled when it is clearly impossible to believe.

Ebert should know better. And so should his readers.

The Oxford Comma

Booksquare has written a passionate defense of the serial comma, pointing to Brenda Coulter’s equally vivacious endorsement of a puncutation mark too frequently used by investment bankers.

While I admire their brio, I must respectfully disagree with these two lovely bloggers. The serial comma (also referred to as the Oxford comma, the Harvard Comma, the pretentious comma, the party-pooping comma, the humorless comma, the comma with the chip on its shoulder, the comma that won’t put out, the comma that would never join a Bunny Hop, the monastic comma and the comma that won’t sing “Comma Chameleon”) takes the fun out of a lengthy list. It is utterly redundant. It insults the readers’ intelligence. Most importantly, in nearly every circumstance, it comes across as the most lifeless and stiffest puncutation mark ever devised.

Consider the fun of a sentence like:

The gigolo ordered bananas, peanut butter and jelly.

Now did the gigolo order bananas and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich? Did the gigolo order a bananas served with a side of peanut butter and jelly? Or did he order three separate items? It’s the kind of amiguity that makes life (and the sentence) quite interesting. Do people order bananas in an unusual manner? That’s fun!

Of course, when we add the Oxford comma, the sentence becomes disappointingly clear:

The gigolo ordered bananas, peanut butter, and jelly.

Now granted, as pointed out by Teresa Nielsen Hayden, there are some instances in which being explicit is necessary. The sentence, “On his journey, he encountered George Bush, a genius and cunnilingus expert,” is of course quite problematic. But given that the English language is already a troubling bundle of inconsistencies, why prohibit its use in toto? Why not keep the reader guessing? Can not a reader figure out that George Bush is entirely discrete from the other two parties!

While it is true that Strunk & White endorse the serial comma (under Section II, Rule 2), I contend that this particular puncutation rule does not apply, because their hearts are not completely into it. They write:

This is also the usage of the Government Printing Office and of the Oxford University Press.

And while I’m normally a big Elements of Style booster, let us consider that even the most virtuous and adorable authorities are capable of slip-ups. The Government Printing Office, folks! Was ever a more lifeless entity ever cited by Strunk & White?

Let us also consider that the hard-core serial comma boosters are found most frequently in law firms and investment banking firms. And what business do such lifeless husks have dictating the English language? What we have here is a clear war on fun and ambiguity.

Now a person by the name of Miss Grammar concludes, “Except for journalists, all American authorities say to use the final serial comma,” and remains puzzled by the fact that a substantial chunk of writers and English mavens still rebel against this. Consider that Vassar has issued a supplement to Strunk & White. AP Style is against the serial comma. So perhaps this isn’t a case of total prohibition or complete sanction, but rather a situation in which, like any helpful tool, you can use the tool or not use it.

But it’s certainly reassuring to know that, on this grammatical point, the earth will continue to rumble.

Note to the Government

I am not afraid, you bastards. Accuse my friends and me of terrorism all you want. But I will not let it sully the sting of my pen. If that means going to jail and being tortured by atavistic goons without due process, all because I called Bush a moron (is that really terrorism?), then so be it.

Notice Served

In the meantime, there’s the return of the LATBR Thumbnail.

The 12 Cartoon Trainwreck

If riots weren’t enough, it seems that the top editorial brass of The New York Press has resigned because the NYP publisher got cold feet over publishing the infamous Muhammad cartoons published by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten.

I have little to say on the matter that Laila hasn’t said already, but with the exception that reprinting a cartoon doesn’t necessarily mean that you subscribe to its message or that you are even subconsciously declaring to someone that their views are worthless. If anything, this whole mess limns in full the mighty communicative gulf between East and West, Muslims and Christians, and violent provocateurs and nonviolent provocateurs. But for the Western newspapers, in the end, this is as clear-cut as shouting fire in a crowded theatre. Yes, the freedom and the right to say it is there. (See Brandenburg v. Ohio 395 U.S. 44.) But know what you are unveiling when you say it. The fundamental distinction lies not with the message, but with the separation between speech and action.

Bus 8662

It happened again on the way back from my improv class. On Tuesday night, at around 10:15 PM, on a 43 Masonic bus headed south, I found myself in David Lynch territory. I’ve long believed that the true San Francisco nutjobs can be found in the so-called affluent neighborhoods, and yet, stupidly, I remain puzzled why the “safer” lines in the City prove to be the strangest. (My previous MUNI tale, if you will recall, happened on the 7 Haight.)

I climbed aboard Bus 8662, flashing a smile and my Fastpass. The driver gave me a lengthy leer and stared down at a paper bag I was carrying. My crime? Holding a bag containing an overpriced pita. How dare I take home a long deferred dinner! On his bus, no less!

I was delighted to find one of my classmates on board the bus. So I said hello to him, complimenting him on the progress he had made in the class. As I was getting situated in the double seat across the aisle from him, the bus took a curve through the Presidio at about 45mph, tossing me back into the adjacent seat like a potato bug flicked over by an eight year old.

“Well,” I smiled after my rebound, “this should be an interesting ride.”

“A BUS IS A VERY POWERFUL THING. THERE’S A LOT YOU CAN DO WITH IT,” boomed a flat and ominous voice from the front. “I SHOULD KNOW. I’VE BEEN DRIVING A BUS FOR TWENTY YEARS.”

For some reason, I thought that this had come from some passenger who was experiencing a harmless bout of psychosis and had somehow confused himself for the bus driver. Someone whom I could quite easily ignore while my classmate and I chatted. But when this statement was followed up with diabolical laughter and a sudden shriek of the brakes, causing us all to lurch violently forward, I suddenly realized that the man who had uttered these words was, in fact, driving the bus.

“HAVE A NIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIICE EVENING,” he said to some passenger exiting the back door, sounding distinctly like an undertaker who hadn’t left the mortuary in years. “HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!!”

The bus suddenly grew terribly quiet as this dawning realization settled in. The driver was fond of jerky transitions between lanes, unannounced slams on the brakes and gas pedal, and slight weaving in the lane he was driving in. Thank goodness there were very few cars on the streets.

We were at the mercy of a maniac. I began watching other passengers getting on the bus and they were utterly terrified.

Clearly, there was only one thing to do.

“So anyway,” I said nonchalantly to my classmate, “great work tonight!”

Suddenly, I heard diablolical laughter from the BACK of the bus. One of the passengers, an inebriated, long-haired and quite possible homeless man in his late thirties, had cracked!

Now I should note that my classmate and I were sitting in the middle of the bus. And at each pole of the bus’s axis, there was a maniac! One a driver, one a passenger. It was the perfect metaphor for MUNI’s problems. I wondered if we were part of some psychological experiment, perhaps an homage to Milgram that involved game theory and kinesiology. But then I recalled the MUNI assault that went down on Sunday. Clearly, if I was driving a bus after that, I’d be more than a little frightened myself. But taking it out on the passengers?

“HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!!”

Silence.

“IS ANYONE TAKING NOTES?”

My notepad was in my pocket, but I didn’t need it. I wouldn’t be forgetting this bus ride even if Alzheimer’s struck me down. The number 8662 was clear as a bell — its white permanent digits nestled within the black expanse of the front, where the driver was laughing and weaving and presumably cradling either a .45 or a Zooka Pop Pistol.

I witnessed a cab pull in front of the bus. The driver skirted the bus around it.

“DID YOU SEE THAT CAB? I COULD HAVE DRIVEN RIGHT INTO IT. HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!!”

The drunk at the back laughed again. Clearly, he had found his soulmate. I decided to laugh along with them. After all, shouldn’t psychotic laughter come in threes?

“Well,” I told my classmate, “if I have to die this way, you’re a standout guy to leave the earth with.”

I then asked my classmate if he was a religious man and if he wouldn’t mind a non-ordained, self-declared minister baptizing him in the event of his untimely death.

I pulled the cord for my stop and wondered if the man would actually pull over. To my amazement, he did.

I wished my classmate long-term health and safety.

“HAVE A GOOD NIGHT. HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!!”

“Good night! Good therapy!” I responded in my best Shakespearean theatrical tone.

The pita, incidentally, was quite tasty.

Roundup

- Georgia fundies won’t be able to enjoy their tax-free Bible purchases anymore. (via the new and improved Book Ninja)

- T.C. Boyle’s Talk Talk, not even out yet, is being turned into a movie. (via Manly Man)

- Ed Falco himself is on deck today at the LBC. Do be sure to ask him questions.

- Just when you thought Leo “When I Need You” Sayer had served his purpose and disappeared from the face of the earth (well, only to torture you over the speakers during a late-night Denny’s meal), the 70s pop song falsetto now fancies himself a novelist. The protagonist? A musician, of course. “[A]ll the people I would have loved to have been.”

- Richard Russo, tax incentive booster?

- Working an STD booth: the source of poetic inspiration.

- What the hell? Who killed Curious George co-writer Alan Shellack? Why would anyone want to kill a man who wrote pleasant stories about monkeys?

- Good news: The Electric Company is on DVD. Bad news: Dave Eggers wrote the liner notes.

- Bill Nye: no longer a bachelor.

- B on illicit file sharing.

The Coretta Scott King Funeral: Summary

CARTER: I hope we can take the opportunity to remember what Coretta Scott King stood for.

BUSH, JR.: Coretta, Coretta, terruh, war, don’t listen to Kayne West.

CLINTON: Yes, I too am a white ex-President. I’m sorry. But don’t blame me. I spoke in many African-American churches when I had something to gain, such as a second presidential term. Now, not so much the case. But Hilary, who is likely running for President in ’08, might do this too. This is what Coretta would have wanted: blatant opportunism. Have I finished seducing you?

LOWERY: George Bush doesn’t care about black people.

MICHAEL BOLTON: They put me here because Stevie Wonder’s feeling a little under the weather.

BUSH, SR.: Reverend Lowery, shut up, boy, and shine my shoes.

ANGELOU: I know why the caged bird sings. And so do you. Let’s just hope the press is awake to spot the absurdities we’re experiencing today.

Lying Novels and the Novelists Who Tell Them

Forget James Frey. The real liar is Neil Gaiman. More inveterate than John Banville.

Side By Side On My QWERTY Keyboard

Tim Redmond’s public flailing against Craig Newmark has garnered a few notable responses. Locally, there was a thread over at the SFist, in which mystified San Franciscans responded. More prominent, however, is Anil Dash’s rant against predictable liberalism and defensive newspapers.

But what I see here in all these reactions is hostility and divisiveness from both sides. (I still remain as baffled as Dave Barry was by a Chronicle reporter’s recorded comment, “I have podcasted. I’m not a complete idiot.” And I have, in a few private incidents, been privy to outright hostility from print reporters when trying to piece together a story.) The journalist boosters note the online paucity of what Crooked Timber’s Henry Farrell has identified as a a “comprehensive, neutral and authoritative argument” (emphasis in original). The online boosters decry how out-of-touch the journalists are, pointing out the new playing field requires people to keep current and unfettered. But both parties share an fascinating and one-note view: the reactionary need to keep both forms separate and discrete, as if bloggers and journalists should be neatly arranged into some red state-blue state dichotomy.

Yes, newspapers will dip their toes into the podcast arena, as admirably as the Chronicle has. But they will do so without understanding the podcast’s personal, subjective and, one might argue, authentic and perhaps unpolished form. Because there are innumerable blogs trying to get to a story first, the blogger will leap to get her hands on a story quick. But because the work is rushed, there will be mistakes and corrections — the possibility that misinformation might sneak through the cracks and be further disseminated.

But at the risk of allowing my idealistic side to come through, isn’t this all pretty silly? One would think that journalists, many of whom are intimately familiar with the innovations of gonzos like Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson and George Plimpton, would embrace an alternative after decades banging out the same who what when where why template. Likewise, one would think that the bloggers and the podcasters would see the creative and informational value of limitations, much less holding onto a story until more confirmed information has come in.

As someone who has worked both sides of the spectrum, I’m wondering why, in all the ink that’s been spilled on the subject, so few people are willing to put their bile aside and contemplate some hybrid of the two forms. You want to talk Web 2.0? Let’s try fusion. What if the newspapers hired more bloggers and podcasters? What if bloggers set self-imposed limits on their content or made more phone calls instead of relying exclusively on Google search results?

Anger, arrogance and dismissiveness might make a writer feel good and drum up some initial attention. But take it from a piss-and-vinegar guy like me: it’s the ideas, multilateralism and flexibility that will stand the test of time. I fail to understand why the blogging/journalism war has become as inflammatory as the situation in Beirut. Surely, both sides have much to learn and benefit from each other.

Why I Will Never Have Anything to Do with Reese Witherspoon

He sleeps with the fishes. Will the E! correspondents who mocked Reese’s fashion sense be next? (via Quiddity)

My Kicking Fetish

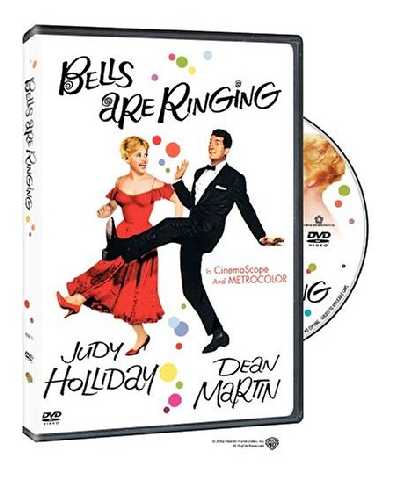

Okay. I’ll confess. Every so often, in a moment of weakness, I’ll jump for something based off of a cover.

EXHIBIT A: The cover of The Bells Are Ringing. This was added to my DVD rental queue because, aside from the strange combination (well, to me anyway) of Judy Holliday and Dean Martin appearing in the same film, who can resist the image of Dean Martin kicking his leg into the air while Judy Holliday is slightly insocuiant about it? I’m telling you. Legs kicking in the air! It’s my downfall.

Yes, I have a kicking fetish.

I should also point out that as a kid, I had an obsession with the Rockettes — in large part because I always associated them with kicking. Which either makes me extremely gay or just plain deviant.

When watching football, I think the punter is the most impressive player. Or at least, I’ve always thought that he does the most work. Because the arm is far more precise, whereas the foot is not. Even if he is a microscopic dot from really bad seating, you’ll always see his leg in the air without binoculars. But a quarterback’s snap? Not always.

My favorite moment during a crime drama was always when they kicked the door in. And the thing that most impresses me about horses is when a horse somehow kicks down a stable door, or when a horse proves to the foolish human trying to tame it that it is the master by whinnying and standing on hind legs.

It’s my firm belief that people should kick more. Or at least realize that their legs are good for a lot more than walking or running.

Leaping, of course, has some acceptance in our society. But kicking? Not so much. It may, in fact, have something of a stigma attached to it. Likely because kicking is considered more of a threatening physical action rather than something which permits excess energy to be happily applied to the leg. In fact, why permit kicking to remain in its default emotional setting? Kicking can be joyful, artistic, and just downright goofy.

The solution here, of course, is to get all happy kickers together in an arena and demonstrate to the world that it’s okay to kick from time to time. There’s no shame in kicking. And yet even sex manual authors sometimes overlook the kick’s possibilities.

Kipen Update

David Kipen, whose The Schreiber Theory has just hit bookstores, sends word that he’ll be hitting numerous California bookstores in February and March. More info on these events can be found at the Melville House site. And an impromptu interview with Kipen can be heard on Show #2 of The Bat Segundo Show.

Time Warner Book Division Sold

Three Hours of Sleep

In lieu of content here today, we direct you to the following places:

- At the LBC site, this week’s it’s Edward Falco week. There’s a podcast interview, as well as the beginnings of a weeklong transcript of beer-fueled discussion with Scott, who quite rightly comes across as more coherent than me.

- And speaking of the LBC, David Milofsky has written an article for the Denver Post. Both Mark and the tireless Dan Wickett get some nice airtime.

- I finished Perlman’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, along with several other books last week. Hope to get to the next 75 Books post soon.

- Even though she lived a long and productive life, I’m still a bit stunned by Betty Friedan’s death, particularly with how metaphorical it is in light of current events, and hopefully I’ll have something coherent to say on the subject later. But in the meantime, check out Bad Feminist. I’m sure more will weigh in throughout the course of the day.

- Tom Baker as disembodied cell phone conduit? WTF? (via Phil)

- You want quirky pairups? The NYTBR may be inept on this score, but the Washington Post has paired George R.R. Martin with Stephen King’s Cell. (via Sarah)

- Brian Sawyer on bookbinding.

- “You don’t even know how to spell Delany, bitch.” The “Rick James, bitch” for speculative fiction fans? You make the call.

- Tayari Jones has posted 175 words of her new book.

- Support Pete.

- David Foster Wallace — is he a cunt?

- The Super Bowl and its commercials? Let me put it to you this way. The cheeseball Patrick Swayze TV movie I had on mute last night while finishing up the podcasts was more enthralling.

- More later.

The Bat Segundo Show #20

Author: Dave Barry

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Reduced to second-string narrator.

Subjects Discussed: Suze Orman, footnotes, Donald Trump, lawsuits, phone calls from Paul Anka, daily affirmations, indices, sex with ducks, buzz cuts (1960 vs. 2005), the boomerang generation, getting reviewed in the NYTBR, Dave Barry deconstructs our Young, Roving Correspondent’s baroque speaking style, snobbery, humor, Lee Eisenberg, commuting, podcasting, reading books and farting, quitting his column, reader expectations, and working with Jeff McNelly.

[LISTENER’S NOTE: This podcast is probably the strangest one we’ve put out.]

Fast Thinking

A brilliant piece of local legislation across the Bay.

A Question for Language & Audio Geeks

In the course of engineering audio, I’ve noticed that the bilabial plosive (meaning the b sound when voiced and the p sound when voiceless) is sometimes recorded with too much gain, even when I have placed the microphone at a reasonable distance from the mouth. Meaning that when I open up an audio file, whenever someone says “book” or “picture,” I must meticulously correct it in postproduction. Not having an expensive processing unit, I am wondering if there is a workaround that would save me such time. (I am guessing that switching to condensers is probably the answer.) I am also curious why the bilabial plosive is so prominent (particularly in deep-voiced male speakers). Could it be the not bad yet dynamic microphone I am using? Or perhaps the signal is simply coming in too high.

[UPDATE: It may in fact be audio compression (PDF), but if other podcasters are having sibilance issues, please offer your thoughts, theories and solutions in the comments.]

RIP Betty Friedan

Details. Damn.

The Office

Earlier in the year, I gave the U.S. version of The Office a shot. I had my doubts. To saunter onto the territory of Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant was tantamount to sacrilege. But after a shaky start, the U.S. Office proved that it had the heart, irreverence, dedication and continuous storyline that, while not as good as Gervais, was nevertheless laudable.

But last week’s episode, which dealt with sexual harassment meetings and organized labor, finally equaled the Gervais-Merchant blend of discomfiting satire and it may very well have surpassed it. Last week’s episode, with its character development, its underlying subtext of corporations crushing the soul out of humanity and the embarassing image of Michael Scott treating a forklift like a toy and driving it into a stack of shelves, pushed The Office into the oxymoron of, dare I say it, vital television.

What makes The Office so important? When was the last time, for example, that you saw any show dramatizing the way a corporation keeps its workers baited for life with impossible dreams (such as the graphic arts training program or the “human” face of a meeting in which extremely personal questions are asked and it’s really more about reporting these things back to HR)? Of course, in a world where you can be downsized tomorrow, these long-term prospects are lilttle more than prospects.

Americans spend forty hours of their week at a job and perhaps ten of those hours stuck in traffic. Out of a 168 hour week, with 56 hours devoted to eight hours of sleep, that’s about half of a waking life devoted to work. And yet there have been very few films and television that have come along to dramatize this middle-class bloc. The reason why a film like Office Space became so celebrated is because there was frankly nothing else out there which has dared to focus on this.

Until, of course, The Office, in both its UK and US incarnations.

To wit: If you are not watching this show, start from the beginning. You will encounter a show that is not only hilarious but has its finger on the pulse of one of the great American hypocrisies.

[ADDITIONAL NOTE: And speaking of television exploring hypocrisy, I should also note that Battlestar Galactica is also strong in its own ways, if only because any program with the line, “One of the nice things about being President: you don’t have to explain yourself to anybody,” is playing quite rightly with fire.]

More YouTube Fun

- William Shatner on a Commodore Vic-20 commercial

- Shatner on computer games: “My problem is…(Shatner pause)…I don’t know how to turn the computer on.”

- Kurt Vonnegut in 1984 “Coffee Achievers” commercial

- Fusion City: hosted by Kate Braverman. “Hey baby.”

- Belgian writer with violinist

- 1985 commercial for Care Bears Books