[NOTE: I did live up to the 75 Book Challenge. The current count for the year is apparently 131, with a few more volumes to be finished before the stroke of midnight. And I’m not even halfway through my writeups. (Again, this list is wildly out of order.) But I’m going to do my best to see if I can get these volumes logged. The problem arises from too much rumination on my end. When I try to write a few sentences, I end up with a paragraph. And so forth. So I’ll see what I can do on this front! But if I don’t get to the end, my profuse apologies. You’ll just have to trust me.]

Book #55 was a reread of Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist. I had read this book at the turn of the century, which seemed fitting given this novel’s preoccupation with the 20th, and marveled then at how Whitehead’s use of language served as a skeleton key that sometimes opened doors containing keen observations about racism and sexism. Now that I’m dwelling upon my reread at year’s end, I’m thinking that if Tom LeClair can categorize the early work of Richard Powers, William T. Vollmann and David Foster Wallace as “prodigious fiction,” perhaps Colson Whitehead might be part of a second wave of “prodigious fiction” — a list that might also include Scarlett Thomas. Certainly, taxonomy is as much of a concern in The Intuitionist as it is to this hypothetical “first wave,” particularly the propriety (or lack thereof) we see with the two warring schools of elevator inspectors: the Intuitionists and the Empiricists. But I believe Whitehead is more concerned with how this arranged information affects existence, as opposed to how it is contained within existence, of which more anon. (Podcast interview.)

Book #56 was Colson Whithead’s John Henry Days. This was the first time I had read John Henry Days. I’d been sitting on this book for a while, deliberately holding off on reading it until a special moment arose. When the opportunity to interview Colson Whitehead arose, I knew that the time had come. This book, I’m pleased to report, was more compelling than I expected. Like The Intuitionist, Whitehead’s set up a niche-based coterie — in this case, a group of freelance journalists whose conduct ascribes to a similar set of rules as the elevator inspectors — with which to launch ruminative riffs on the history of John Henry, Meredith Hunter’s death at Altamont (interestingly, Franzen could not bring himself to name Hunter when he reviewed the book), and Paul Robeson, among many others. And I’d argue that these historical tidbits, combined with eccentric moments which challenge our traditional perspective, exist as a way to process arranged information and track its effect upon culture and racism. Ergo, if a second wave of prodigious fiction can be sanctioned, John Henry Days is quite possibly its greatest exemplar. (Podcast interview.)

Book #57 was Colson Whitehead’s Apex Hides the Hurt. So this was it: the third novel by Mr. Whitehead, the novel that certain pals of mine didn’t care for. I didn’t hate this book. I appreciated its frequent inventiveness. But I didn’t find it nearly as enthralling as Whitehead’s other two books. I think this book misfired because Whitehead didn’t surround his unnamed protagonist with advertising figures who challenged his livelihood. Instead, the protagonist is a free agent who operates on his own terms, with a particularly melodramatic figure as one of the foils (a millionaire by the preposterous name of Lucky Aberdeen). The book, as a result, is an enjoyable if pale shadow if the two previous novels. (Podcast interview.)

Book #58 was Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. I can understand the antagonistic reactions to Foer’s second book. I don’t quibble so much over the book’s child genius protagonist or even its associations with September 11, but I think Updike was right to suggest that Foer could use “a little more silence, a few fewer messages.” This book often contains playfulness for playfulness’s sake. Gilbert Sorrentino, this is not. Because of the large volume of “playful” experiments, I was unable to penetrate the novel’s heart. Nevertheless, know that I read and save every Foer book, with the hope of one day being able to treat JSF with the proper adulthood he deserves. Until that day, Extremely Loud is clearly the work of a kid still playing around. (Podcast interview.)

Book #59 was Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying. I was probably the last person on earth who hadn’t read this book. This novel was daring for its time. But I found myself more fascinated by Isadora Wing’s neurotic narration, an introspective juggernaut of questions which suggests that gender relations haven’t changed nearly as much as we believe they have, than Wing’s sexual affairs. Thirty years later, the adultery here is no more daring than Peyton Place. But at some point, I hope to investigate the book’s three sequels. (Podcast interview.)

Book #60 was The May Queen, edited by Nicole Richesin. Some of my thoughts on this light but entertaining anthology are contained within my mammoth report from April. (Podcast interview with May Queen contributors.)

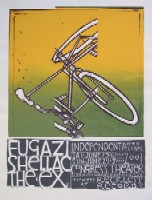

Book #50 was Jay Ryan’s 100 Posters, 134 Squirrels. I was turned onto

Book #50 was Jay Ryan’s 100 Posters, 134 Squirrels. I was turned onto  Book #55 was Sarah Waters’ The Night Watch. Contrary to other reports, this isn’t a total departure from Waters’ other romps, but this fascinating novel is an inevitable evolution — the absolutely right step for Waters to take as an author. I’ve come to the conclusion that, for a literary author, the fourth or fifth novel is often the make-or-break point for stylistic evolution. Consider David Mitchell’s successful transcendence from baroque plots into the deceptively simple Black Swan Green. Or Martin Amis’s Money. Or Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn. Or Richard Powers’ defiant swing into dystopia with Operation Wandering Soul, followed by the metafictional Galatea 2.2. These were all moves that nobody could see coming. And I would argue that The Night Watch can also be added to the long list of transition novels which demonstrate that an author is more than we expect her to be.

Book #55 was Sarah Waters’ The Night Watch. Contrary to other reports, this isn’t a total departure from Waters’ other romps, but this fascinating novel is an inevitable evolution — the absolutely right step for Waters to take as an author. I’ve come to the conclusion that, for a literary author, the fourth or fifth novel is often the make-or-break point for stylistic evolution. Consider David Mitchell’s successful transcendence from baroque plots into the deceptively simple Black Swan Green. Or Martin Amis’s Money. Or Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn. Or Richard Powers’ defiant swing into dystopia with Operation Wandering Soul, followed by the metafictional Galatea 2.2. These were all moves that nobody could see coming. And I would argue that The Night Watch can also be added to the long list of transition novels which demonstrate that an author is more than we expect her to be.