Alex Beckstead appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #251.

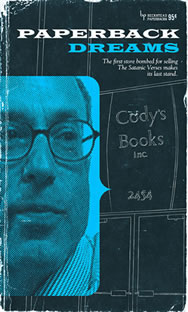

Mr. Beckstead is the filmmaker behind Paperback Dreams, a documentary on independent bookstores. The documentary is now touring around the nation and is making appearances on PBS.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Surrendering to hard-boiled journalists.

Guest: Alex Beckstead

Subjects Discussed: Why Beckstead singled out Cody’s and Kepler’s over other Bay Area bookstores, Kepler’s as a prominent fixture on the Menlo Park town square, the Cody’s “hail Mary” play in San Francisco, business location problems in Union Square, the commercial viability of Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, the Bay Bridge as the cultural Berlin Wall, the question of why Cody’s didn’t survive in the present age when it survived the seedy environment of the 1960s and the 1970s, economic vs. cultural shifts, passion and independents, the absurdity of buying everything online, Amazon, bookstore proprietors who don’t own their buildings, the graying of bookstore customers, Andy Ross vs. Clark Kepler as successful bookseller, the independent bookstore as cultural space, listening to the customer base, the importance of being an entrepreneur, comparisons between bookstores and movie theaters as glorified snack bars, the two storefront dilemma, the bookseller as philanthropist, an independent bookseller’s responsibility to the community, the conglomeration of publishers and the lack of dangerous books on the market, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and the Cody’s firebombing, books vs. music as a medium, whether or not the Internet is bad for books, gatekeepers, the importance of the countercultural movement to independent bookselling, and the ubiquity of Amazon vs. the selection of a bookseller.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Beckstead: I didn’t smell blood in the water. I didn’t go in thinking, “Okay, well this is going to be a failure.” I mean, it was a huge risk. The kind of thing that Andy [Ross] was doing, there was going to be a dramatic outcome one way or the other. Either he wasn’t going to make it and then the losses were going to be catastrophic or he was going to make it and sort of prove that somewhere, somehow, an independent bookstore can still make it. That was the outcome I was still rooting for. But that’s not what happened.

Beckstead: I didn’t smell blood in the water. I didn’t go in thinking, “Okay, well this is going to be a failure.” I mean, it was a huge risk. The kind of thing that Andy [Ross] was doing, there was going to be a dramatic outcome one way or the other. Either he wasn’t going to make it and then the losses were going to be catastrophic or he was going to make it and sort of prove that somewhere, somehow, an independent bookstore can still make it. That was the outcome I was still rooting for. But that’s not what happened.

Correspondent: But simultaneously, you do have footage of Andy Ross, as the bookstore is opening. He’s saying very proudly in the streets how banks won’t lend him money, how he’s putting his entire savings into this “hail Mary” — we’ll call it that, I suppose, because it did indeed go belly up. And at the end of the film, he even says, “This was a colossal act of hubris.” I mean, this store was operational at the expense of the Telegraph store.

Beckstead: Well, the Telegraph store wasn’t making money. That’s what people need to understand. You know, the Telegraph store was not going to survive. It might have limped along for another year or two, had Andy not opened San Francisco. But it was losing a lot of money. The kind of books that historically sold were not selling well there. And I think Andy’s reasoning was that, when they opened the second store in Berkeley in ’98 — you know, Cody’s on Fourth Street — that store became very successful very quickly. It was smaller than Telegraph. There’s a whole other thing about Telegraph. It’s always been a little edgy, but it’s kind of got a little bit seedy. There’s a high rate of vacancies along Telegraph Avenue. I was talking at one point, when we were making the film, with the owner of Ameoba Music. He has a very large record store on Haight Street in San Francisco and then also on Telegraph. It’s still not clear to me exactly who’s to blame for the decline of Telegraph. But it’s clear. He was saying that there’s hardly any vacancies on Haight Street. It’s very similar in terms of the kind of people who spend time there. Similar problems with aggressive panhandling. With drug dealing and all those sorts of things. But Haight Street does fine. For some reason, Telegraph does not.

Telegraph was in decline. Fourth Street was really taking off as a shopping district. I can’t remember the exact number, but it’s something like 20 to 30% of the sales tax revenue for the City of Berkeley comes from Fourth Street. And Cody’s was the biggest shop on the block. They were the anchor on Fourth Street. So I think Andy’s logic was: We opened a second store in a more upscale shopping neighborhood. That quickly became profitable. Not quite profitable enough to hold Telegraph as well. But maybe if we did the same thing on a bigger scale, then we’d have two successful stores and one that was kind of slowly dying. But maybe we could subsidize it long enough to figure out what was going to happen. I mean, there’s been talk of turning around Telegraph Avenue for years. So I think that he was really optimistic that you could do that. But, yeah, it wasn’t the right call at the end of the day.

BSS #251: Alex Beckstead (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Listen: Play in new window | Download

I have learned that Thomas Gladysz, the events coordinator for the now less wonderful San Francisco bookstore Booksmith, has been let go by new owners Christin Evans and Praveen Madan. No explanation given, but presumably it’s “the economy.” Thomas had been at the Booksmith for 21 years, and the man had events coordination down to a science. Not only was he one of the vital guys who held the Haight’s literary community together, but he was always very kind and courteous — even to loudmouth regulars like me. One of his many achievements involved organizing and hosting Allen Ginsberg’s last reading — this, when the man was dying. Without Thomas, the bookstore simply won’t be the same. I recognize the need for change in this ever-shifting economy, but getting rid of Thomas is hardly conducive to making a store “an integral part of the neighborhood,” as the smug Chuck Nevius boasted only a few weeks ago. Evans and Madan owe the San Francisco literary community a transparent explanation for this disgraceful move. Canning veterans like Thomas is hardly “building the independent bookstore for the 21st century,” as the Booksmith’s website now boasts. It’s more like lopping off one of the legs that made the bookstore a serious player in the first place. (Rather criminally, there is no mention of this terrible news at SFist or the ostensibly Bay Area-based litblog, Conversational Reading. What a way to stand up for the little guy. For goodness sake, Smokler, can you look into this story?)

I have learned that Thomas Gladysz, the events coordinator for the now less wonderful San Francisco bookstore Booksmith, has been let go by new owners Christin Evans and Praveen Madan. No explanation given, but presumably it’s “the economy.” Thomas had been at the Booksmith for 21 years, and the man had events coordination down to a science. Not only was he one of the vital guys who held the Haight’s literary community together, but he was always very kind and courteous — even to loudmouth regulars like me. One of his many achievements involved organizing and hosting Allen Ginsberg’s last reading — this, when the man was dying. Without Thomas, the bookstore simply won’t be the same. I recognize the need for change in this ever-shifting economy, but getting rid of Thomas is hardly conducive to making a store “an integral part of the neighborhood,” as the smug Chuck Nevius boasted only a few weeks ago. Evans and Madan owe the San Francisco literary community a transparent explanation for this disgraceful move. Canning veterans like Thomas is hardly “building the independent bookstore for the 21st century,” as the Booksmith’s website now boasts. It’s more like lopping off one of the legs that made the bookstore a serious player in the first place. (Rather criminally, there is no mention of this terrible news at SFist or the ostensibly Bay Area-based litblog, Conversational Reading. What a way to stand up for the little guy. For goodness sake, Smokler, can you look into this story?)

Beckstead: I didn’t smell blood in the water. I didn’t go in thinking, “Okay, well this is going to be a failure.” I mean, it was a huge risk. The kind of thing that Andy [Ross] was doing, there was going to be a dramatic outcome one way or the other. Either he wasn’t going to make it and then the losses were going to be catastrophic or he was going to make it and sort of prove that somewhere, somehow, an independent bookstore can still make it. That was the outcome I was still rooting for. But that’s not what happened.

Beckstead: I didn’t smell blood in the water. I didn’t go in thinking, “Okay, well this is going to be a failure.” I mean, it was a huge risk. The kind of thing that Andy [Ross] was doing, there was going to be a dramatic outcome one way or the other. Either he wasn’t going to make it and then the losses were going to be catastrophic or he was going to make it and sort of prove that somewhere, somehow, an independent bookstore can still make it. That was the outcome I was still rooting for. But that’s not what happened.