To my great surprise, Gemstone Publishing sent me two volumes of their EC Archives reprint series.

First off, a few words about EC Comics: I came of age decades after their inception and, as a great fan of William Gaines’ work on MAD, I was very curious about them as a young lad. Much like video games and industrial music were the MacGuffins for Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold’s murderous rampage in Littleton, EC Comics, thanks in part to persnickety psychologists, had been declared the cause of juvenile delinquency, leaving Gaines to find creative ways to bypass the Comics Code Authority’s often draconian demands.

I spent many years trying to track these mythical comics down and, at first, had very little success. But I did manage to track down a few reprints, inexplicably available at my public library, and began to see why Stephen King was inspired by them for Creepshow. The stories were unapologetically lurid, punchy, and featured all manner of colorful violence. They were often absurd, but they certainly grabbed your attention.

Years later, now that I have a more trained narrative eye, the stories are no less ridiculous; perhaps they are even more so. In the first story contained within Weird Science, Volume 1, a scientist is accidentally sprayed by an atomizer and begins to shrink in size. But this is no mere Richard Matheson ripoff. Each atom is actually a world, which in turn is composed of atoms, and, as the scientist continues to shrink, he encounters all manner of new civilizations. That all this is contained within an eight page story is fascinating enough. And it’s safe to say that this premise is hardly scientific. But in playing fast and loose with the rules of reality and keeping the pace swift, there’s still something oddly compelling about the scientist’s plight.

Of course, women regrettably come second in the EC Comics universe. I find myself troubled that they are reduced to being mere providers, often serving as trophies that men display to other men. (“Beautiful wife” is a recurrent appellation.) There is, in addition, a tendency for older men to call their younger apprentices “boy,” leaving me to ponder hypothetical homoerotic undercurrents.

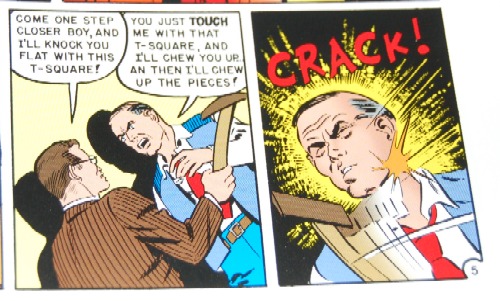

At the same time, where else are you going to find such crazy dialogue like “Come one step closer boy, and I’ll knock you flat with this T-square?” or a monster remarking to surprised humans, “You see, I’m quite friendly! Come here!”

More than twenty years after I experienced EC Comics for the first time, Gemstone offers another chance to experience the strangely entertaining parameters of the EC Comics universe. I’m struck by the attention to unusually tight panels for dramatic emphasis and the eye-popping characters. (It is almost as if every character has their pupils permanently dilated.) But even with often bizarre and unjustified premises (such as a house that inexplicably shifts at various points in time without explanation), you have to admire EC’s narrative audacity, even if it remains permanently rooted in a decidedly 1950s style of subversiveness. And there’s the added bonus of seeing how such artists as Harvey Kurtzman and Al Feldstein fared when they weren’t inking satirical stuff for MAD.