RIP Denis Twitchett and Doris Muscatine.

Category / Obits

RIP John McGahren

Dead at 71. (via Mark)

RIP Stainslaw Lem

Also

Charles Newman has died, and Sam Jones is on the case.

Sometimes There’s a Little Whammy in Everyone

Peter Tomarken tried to press his luck with a plane but stopped at a whammy. RIP Peter Tomarken. Press Your Luck was a game show staple on lazy summer mornings back in the 1980s. And Tomarken’s enthusiasm was strangely infectious.

As an aside, maybe it’s just me, but why do game show hosts seem to suffer macabre deaths? Consider also:

Larry Blyden, host of What’s My Line? and To Tell the Truth: Goes to Morocco on vacation and dies because of injuries sustained in a car accident.

Ray Combs, host of 1988-1994 syndicated reincarnation of Family Feud: Gets depressed after being canned from Family Feud and hangs himself in psychiatric ward hospital room.

(via Pamie)

Not Another One

RIP, Gordon Parks. A photographic genius and the director of one of the all-time great blaxploitation flicks, Shaft.

RIP Dana Reeve

As if Christopher Reeve’s untimely paralysis death was sad enough, Dana Reeve passed away. She was only 44. She did not smoke and yet somehow died of lung cancer.

[UPDATE: Elizabeth Crane offers some personal thoughts on Reeve’s death.]

And Otis Chandler Too…

Goddam

Dennis Weaver too? Jesus, what a lousy couple of days. I’ll always remember Weaver’s fantastic performance as the Night Man from Touch of Evil.

RIP Frederick Busch

Novelist Frederick Busch also passed over the weekend and Slushpile is on the case.

Octavia

1987. Sacramento. I was in eighth grade and my best friend was African-American. And he was a handful of African-Americans in a school comprised almost entirely of whites. This made no difference to me. I was simply relieved to meet someone who dug Full Metal Jacket and Doctor Who as much as I did and who liked to contemplate some of the strange observations around us. The girls we blushed over at recess. (Embarassingly, I still blush around women to this very day and I can’t help thinking of my old friend every time I do.) We’d go crawdad fishing and ride away long weekends on our bikes. We exchanged rap tapes. Kool Moe Dee, Too Short (before the $ sign), Ice-T. He introduced me to his friends and I’d hang out with the posse contemplating Arsenio Hall’s appearance in Amazon Women on the Moon and trying to figure out which girls had the best booties. His mother, who raised my friend on her own, was kind enough to let me stay over and she somehow knew that things weren’t exactly scintillating at home. But no matter.

What I had no way of knowing back then, what indeed was a horrible mystery to me, was when I came home with black eyes and bruises and horrible aches in my pale and skinny limbs simply because this boy was my best friend. I was called “Nigger Lover.” I was punched and beaten, thrown into trash cans and mercilessly taunted between periods. For what crime? Partly because I was poor, but mostly because I hung out with a kid who was not of my race. This was not the South, but suburban California. How could this be? I asked myself. Hadn’t these days passed?

Eventually, my friend had to move away to St. Louis. His mother had found a better-paying job. And I lost track of him. I’ve made several attempts over the years typing his name into search engines, aching to know what happened to him, wanting to make sure that he made out all right. But I’m pretty sure he made out okay. He was a good kid.

Back in those days, I was a heavy reader of science fiction. Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Robert Sheckley, Richard Matheson, Harlan Ellison, Robert Bloch, and Douglas Adams were all names that graced the covers of the books I read. Fantastic worlds reflecting the phantsmagorical awaited me in the library. But when I checked out a mass-market paperback of Kindred from the library, I had no way of knowing that it would be Octavia E. Butler who would tell me, perhaps more substantially than the others, just what speculative fiction was all about and why my schoolmates had beaten the shit out of me more than a century after emancipation. For in Butler’s hands, speculative fiction wasn’t just “speculative.” It was fiction that stood on its own, going well beyond what even my English teachers often dismissed as “flying saucers and bug-eyed monsters.” It unearthed human ambiguity. In one glance from a character, Butler revealed untold decades of subconscioius behavior that our contemporary society had failed to discuss, much less address. And she did so with a clearly written and utterly compelling tale involving time travel and years waiting for one’s lost love to return. It was Kindred which explained to me why I had been hurt and taunted and abused.

That was no small task.

To me, Kindred was one of those key books that told me that literature was about something. Years later, in my late twenties, I reread the book and was astonished by how well it had held up. And with more than decade of life experience accumulated, the chasm between Kevin and Dana hurt even more.

It’s difficult to sum into words just what Octavia E. Butler did for fiction. At the risk of coming across as a jejune generalist, Butler didn’t just demonstrate that science fiction wasn’t the exclusive territory of white male writers, but she proved more adeptly than most writers that issues of race, environment, ideals in a dystopic state, and the like were the stuff of Fiction. Period.

So when Tayari Jones tipped me off this morning with the possibility that Butler had died, before Butler had even had the chance to celebrate her sixtieth birthday, I couldn’t believe it. I had to find out for sure. Surely, the woman who had planned to be an “80-year-old writer” and who had, with Kindred, rediscovered the great joy of writing after the dystopic Parables wasn’t gone. And when I confirmed the news this morning, I was numb and more than a little dumbstruck and really couldn’t do much of damn anything all day.

I’m extremely grateful that I had the chance to talk with her and to thank her. What I can tell you about Octavia Butler from the hour I shared with her is this: I had taken her to a cafe that I thought would be relatively depopulated, but to my great surprise, it was extremely noisy and crowded. I remember buying her a bottle of mineral water, which I had initially misheard as “water.” I remember Butler wincing and raising an eyebrow every time the report of the espresso machine went off. But I also recall her being extremely relaxed and diligent with her answers, even though she didn’t really care much for doing press, much less being in public. Because I knew Ms. Butler had a heart condition, I offered to walk her back from the hotel. But she was a self-sufficient woman and she preceded the walk back to her hotel with an unexpected “It was nice meeting you” and a disappearing act that was so rapid that I rushed out the doors to find no trace of her. I had horrible nightmares that she wouldn’t make it to her City Lights reading that night. But thankfully she did.

In the end, Butler’s work will live on. But there is nobody who can replace her. I can’t imagine any other author who could have helped me understand that I wasn’t alone when the preteen thugs tried to dissuade me from my friendship but completely failed in the process.

[UPDATE: Tayari has more words, as does On the Verge of Dating White Girls and Cory Doctorow.]

[UPDATE 2: And, thanks to Gwenda, more from Jenny D, Scott Westerfeld and Known Forms.]

[UPDATE 3: Still more. Cyborg Demoracy, L. David Wheeler, Earthseed poetry, Kelly Sear Smith, and Pantry Slut, who remembers Butler as a Clarion instructor.]

Octavia Butler Dead

Octavia Butler died on Saturday as a result of a fall from her home in Seattle. I talked with the King County Medical Examiner’s office. They have confirmed that they have an Octavia Butler there. Damn.

This is a major loss to American letters and I’m a bit shaken up by this. I’ll have more to say about Octavia Butler’s importance as soon as I collect myself. But I was extremely fortunate enough to talk with Octavia just before she passed away. You can listen to the podcast here.

The email currently making the rounds:

“Yesterday Octavia Butler fell outside her house during what neighbors thought was a stroke. A neighbor kid found her outside her house. They rushed her to the hospital, and found blood had pooled in her brain, they operated but she passed away today.”

(Source: Steven Barnes’ blog.)

RIP Don Knotts

ROBERTA: Who is this, Enid?

ENID: It’s supposed to be Don Knotts.

ROBERTA: And what was your reason for choosing him as your subject?

ENID: I dunno…I just like Don Knotts.

ROBERTA: I see…interesting.

From Ghost World

Three Items

1. RIP, Coretta Scott King.

2. Most. Predictable. Nomination List. Ever. (More importantly, the Razzies have been announced. Go Uwe Boll!)

3. If you miss tonight’s 2006 State of the Union address, have no fear. It’s exactly identical, word for word, to the 2002 State of the Union. Read the 2002 address and you’ll hear all you need to know about the State of the Union.

RIP Wendy Wasserstein

Dead or Alive?

I died two weeks ago. (Thanks, Mary!)

RIP Vincent Schiavelli

Damn. Another great character actor gone.

RIP John Spencer

Only 58. Damn.

RIP Richard Pryor

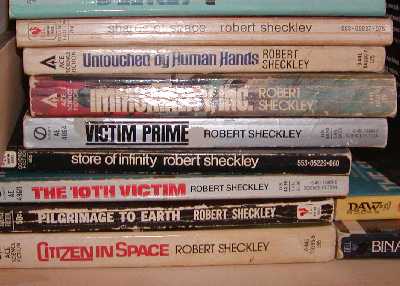

RIP Robert Sheckley

The great satirical science fiction author Robert Sheckley passed away on December 9, 2005. He was 77.

Before Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett (and perhaps Connie Willis), there was Robert Sheckley. Far from a mere wiseacre (although he was that and much more), Sheckley was one of the first authors to fuse satire with science fiction. Years before Stephen King ripped off the idea for The Running Man and decades before the crazed spate of reality television shows, Sheckley had written a short story, “The Seventh Victim,” in 1953, devising a futuristic world in which game show contestants were designated Hunters and Victims and competed for cash by murdering contestants. A film and a novel followed: The Tenth Victim (1965). Here is an excerpt that shows Sheckley in top goofball form:

Before Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett (and perhaps Connie Willis), there was Robert Sheckley. Far from a mere wiseacre (although he was that and much more), Sheckley was one of the first authors to fuse satire with science fiction. Years before Stephen King ripped off the idea for The Running Man and decades before the crazed spate of reality television shows, Sheckley had written a short story, “The Seventh Victim,” in 1953, devising a futuristic world in which game show contestants were designated Hunters and Victims and competed for cash by murdering contestants. A film and a novel followed: The Tenth Victim (1965). Here is an excerpt that shows Sheckley in top goofball form:

Long legs flashing, sable coat clutched beneath one arm, Caroline ran past the tawdry splendors of Lexington Avenue and fought her way through a crowd gathered to watch the public impalement of a litterbug on the great granite stake at 69th and Park. No one even reamrked on Caroline’s progress; their eyes were intent on the wretched criminal, a lout from Hoboken with a telltale Hershey paper crumpled at his feet and with chocolate smeared miserably on his hands. Stony-faced they listened to his specious excuses, his pathetic pleas; and they saw his face turn a mottled gray as two public executioners lifted him by the arms and legs and lifted him high in the air, positioned for the final plunge onto Malefactor’s Stake. There was a good deal of interest just then in the newly instituted policy of open-air executions (“What have we got to be ashamed of?”) and not much current interest in the predictably murderous antics of Hunters and Victims.

Note the specific details nestled within these lengthy sentences. We have here a ridiculously picayune offense attracting a mob, complete with the attention given to the “telltale Hershey paper crumpled at his feet.” Not only is this “criminal” being executed for a trivial offense, but this is no mere hanging, but a more atavistic “impalement.” There is an enduring rivalry between New Jersey vs. New York, as if the crowd completely expected some lout from Hoboken to sully their neighborhood. Further, murder, by way of being televised, has been marginalized and is now devoid of the appropriate horrific response.

When Sheckley came along in the 1950s, speculative fiction needed a swift kick in the ass. While early innovators such as Alfred Bester and Fritz Leiber were just beginning to expand the genre’s limits (all to come full circle in the so-called “Golden Age” of the 1960s) beyond alien empires, robots and humanity’s skirmishes with extraterrestrials, Sheckley had a decidedly more mischevious purpose.

Immortality, Inc. (1958) imagined a world in which science had proven that an afterlife existed, but corporations charged exorbitant fees to get there. Dimension of Miracles (1968) concerns a man who wins the lottery, but must return to Earth to get his prize. And getting to Earth, much less the right Earth in the right time, proves a greater struggle than expected.

But Sheckley was far from a mere funnyman. He wasn’t afraid to experiment. His novel, Options (1975), was composed of seventy-seven brief chapters, resulting in a Flann O’Brien style collection of phantasmagorical imagery which may or may not be real.

It’s really too bad that Sheckley spent much of his latter years writing novels for Deep Space Nine and Babylon 5 (sadly, among the few of his works still in print) and never received the full credit he deserved. His work will be truly missed. However, if you’d like to sample, Nesfa Press has issued The Masque of Mañana, which contains Sheckley’s major short stories. They’ve also published Dimensions of Sheckley, an omnibus collection that contains five of his novels.

Failing that, the Robert Sheckley website has preserved a television appearance which was recorded in Romania last year.

Another Day, Another Childhood Icon Gone

RIP Stan Berenstain (via Galleycat)

RIP Link Wray

Link Wray, the father of the power chord, has died. The man who launched a million punk and metal bands through a staggeringly simple concept: top string at set fret, second to top string two frets down. Slide finger formation up and down with sharp strikes of plectrum, feed through loud Marshall amp. Repeat until you stumble upon wonderful noisy song.

Had not Wray come up with this magical concept, I would never have enjoyed so many hours in garages and basements with other like-minded goofballs as a teenager. (Some of the songs I penned during that period include “The Last of My Kind” and “The Cat Must Die.”) Thank you, Mr. Wray, for democratizing rock and roll for those of us whose grasp of pentatonic scales were shaky at best.

John Fowles Dead

BBC: “Fowles died at his home in Lyme Regis, Dorset on Saturday after battling a long illness, his publisher said.” Does this mean a moratorium on scathing reviews for any posthumous journal volumes released from Cape? (via MeFi)

[UPDATE: More on Fowles from Jenny D, who feels that Fowles’ passing marks “the end of an era.”]

[UPDATE 2: Mark has a smorgasbord of links.]

[UPDATE 3: Another tribute from Litkicks.]

China Nishiura Dead

Terrible news for Shonen Knife fans. Shonen Knife and DMBQ drummer China Nishiura was killed last week in a car accident.

RIP Michael Piller

Michael Piller, the man who penned “The Best of Both Worlds” and caused me, in my teenage zeal, to get the satellite feed of Part II days before it aired, has passed on. He was only 57.

Aw Damn…

Don Adams has passed on. Damn.

I grew up with that curious generation just at the beginning of the Internet (i.e., the Usenet days) and near the end of UHF saturation (before I gave up television). And Adams was one of my unspoken comic heroes. If I learned anything from watching Get Smart, it was this: deadpan ardor with dollops of sincerity can get you through a lot of life’s unexpected scrapes. It didn’t help that Smart worked with a damn sexy and damn smart gal named Agent 99.

The Maxwell Smart persona was dug up somewhat with the Inspector Gadget cartoons, but Gadget was only Adams’ voice. And while Adams’ voice, in itself, was intoxicatin, you needed the expressive eyes and the benign look of confusion to get the full schtick. It was not dissimilar to John Astin’s Gomez Adams, an equally exuberant comic figure. But where Gomez invited destruction, Maxwell Smart unwittingly did so. So it’s Maxwell Smart that I remember and I mourn, wondering if there is a single comic actor (let alone an ambitious producer actually concerned with developing a comic character) who can ever fill Adams’ shoes.

RIP Robert Moog

RIP Shelby Foote

As noted elsewhere, Shelby Foote has passed on.

Technorati Tags: Shelby Foote

Miller Gone

Arthur Miller has passed away. He was 89.

I have a tremendous amount of words to unload for just how important Miller was to me, along with considering the influence of The Crucible and Death of a Salesman. But it will have to wait until I get some time.

For now, all that needs to be said is that another genius has left the world, and we are all the lesser because of it.

Guy Davenport Dead

First Sontag, then 100,000+ lives from the tsunami, then Will Eisner, now Guy Davenport. This is a pretty shitty week. Wood S Lot has plentiful Davenport links.