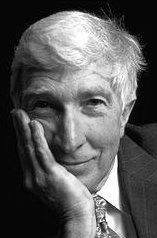

PICTURED LEFT: John Updike: “This middle-aged affluent will self-destruct in five seconds.”

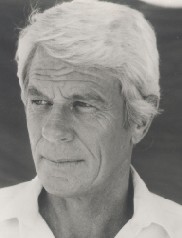

PICTURED RIGHT: Peter Graves: “This message will self-destruct in five seconds.”

Los Angeles Times: “Offers keep coming in, such as the $15 million dangled by Cadillac last year to lease the song ‘Break On Through (to the Other Side)’ to hawk its luxury SUVs. To the surprise of the corporation and the chagrin of his former bandmates, [drummer John] Densmore vetoed the idea. He said he did the same when Apple Computer called with a $4-million offer, and every time “some deodorant company wants to use ‘Light My Fire.’ ”

Laila Lalami asks, in a Powell’s essay, why the impoverished are so underrepresented in current literature. I suspect that there might be similar reasons for why the American novel also fails to acknowledge work or employment, or, for that matter, tales outside that socioeconomic rank favored by our plutocratic society.* It may be too quotidian for those hermetics accustomed to reading flaacid tales of a middle-class, middle-aged Caucasian man having yet another midlife crisis (that hackneyed literary genre best represented by Richard Ford and John Updike that I would style the “middle novel”).

Do the majority of the pepole who read books (i.e., heavy readers who are likely to buy and read at least 50 books a year) have an expendable income with which to afford these books? Is the publishing industry aware of this particular type of consumer and, in some small way, marketing directly to him? Further, are these possibly affluent heavy readers even interested in novels which deviate from their own comfortable class, ethnic and monetary trappings?

Here in America, we’re so accustomed to asking “What do you do?” to someone at a party. If one answers “plumber” or “barista,” an elitist interlocutor will often categorize that person as beneath his class and education, rather than basing his judgment on the individual. If such a mentality has been transposed to how people select and read fiction, then I hope that there’s someway it can be averted. For it’s often the plumbers and baristas who often have pivotal perspectives and important existential answers that are worth considering — particularly, if you’ve lived a lifetime without ever missing a hot meal.

* — The following observation doesn’t deal specfically with literature, but it’s worth considering. Kieslowski’s Bleu tries to explore how much one can find personal liberty while shutting one’s self off from society. But even a master like Kieslowski couldn’t do this without making Bleu‘s protagonist financially solvent. Since most people wouldn’t be lucky enough to live in such a condition, is Kieslowski’s rhetorical question invalidated because it’s not true liberty? Or did Kieslowski take the easy way out? Or have we become so accustomed to the habit of an affluent protagonist that a major overhaul of our hard wiring is in order?

From the What the Fuck Department comes this Caitlin Flanagan review (no surprise) of Peggy Drexler‘s book Raising Boys Without Men (as discovered by Scott). Flangan’s essay originally appeared in The Atlantic and has, much to a thinker’s regret, invaded Powell’s fortifications. Drexler has apparently posited a fascinating thesis: boys raised by women without men (read: lesbians and single mothers, referred to here as “maverick moms”) turn out better than boys raised by mothers and fathers. Instead of examining this interesting premise with some nuance, Flanagan takes umbrage against it, failing to realize that a son “better” raised by a maverick mom doesn’t necessarily translate into a “flawless” adolescence or, obversely, a mom and dad there to “fuck you up” — to use Flanagan’s hyperbole.

Scott argues that the problem with Drexler’s book is that there’s no middle ground. But I would argue that it is Flanagan herself who is incapable of walking the middle ground. This means we have a great problem with how the book is being presented. Because when it comes to something as complex as parental roles and child development, a critic cannot cling to cheap dichotomies like a life preserver if she expects to think her way up the river.

Even if we accept Flanagan’s notion that Drexler presents “the low-down rottenness of men” (nowhere in her review does she present a quote from Drexler’s book supporting this idea, other than the “wounded rhinos” thing, which strikes me as more metaphor than calumny), I’m wondering if Flanagan is threatened by the idea of someone not only pointing out “competition, dominance and control” as male issues, but also Drexler’s suggestion that women can instill some variant of these issues. (By way of contrast, both this review from the San Francisco Bay Guardian and this Library Journal review seem to suggest that Drexler is only stating that “maverick mom” relationships exist as a viable alternative and that might, in fact, be better for the developing child.)

A real critic, even a cogent conservative (cogency seems to have escaped Ms. Flanagan from Day One), might have challenged Drexler on whether or not paternally imbued masculinity is essential to child development. Instead, Flanagan puts crass metaphors into Drexler’s mouth (“In her opinion, maleness is a bit like Jiffy Pop”) and then proceeds to categorize Drexler’s book as “the latest entry” in “‘You go, girl!’ studies,” ending with an antifeminist tirade that has little to do with the book, much less Drexler’s argument.

This is reviewing? I certainly hope that this sort of black-and-white depiction of gender roles isn’t what the Atlantic considers to be the apotheosis of criticism.