Another one of “The Young Writers I Admire” from my 1979 essay was Peter Cherches. Over 30 years ago I was in the first class of MFA students at Brooklyn College and Pete was in an undergrad fiction writing class with my teacher and mentor, Jonathan Baumbach, who introduced us. But I’d already read and liked Pete’s work; like me, he’d published a story he wrote as an undergrad in the London-based Transatlantic Review. Pete is one of the smartest, funniest, nicest writers I know. He uses language with a sense of play that ranks him among the best “experimental” writers. But I’ll let Pete tell his own story:

Long before I reinvented myself as a food and travel blogger, long before there were blogs, I was a “downtown” writer and performance artist.

The recent publication of the anthology Up Is Up, But So Is Down: New York’s Downtown Literary Scene, 1974-1992 (NYU Press) has inspired this reminiscence.

Over the years I’ve published fiction and other short prose pieces (which some choose to call prose poems) in many literary magazines, most with pretty small circulations. Anthologies have exposed my work to wider and quite different audiences. In The Big Book of New American Humor I shared pages with Woody Allen, Seinfeld, Peter DeVries, Garrison Keillor and Philip Roth, among others, a fact that led me to proclaim that I was the only writer in the book I had never heard of. Poetry 180, Billy Collins’ website and anthology originally aimed at exposing high school students to contemporary American poets, surely garnered me my largest audience yet. My entry in Guys Write for Guys Read, Jon Scieszka’s adolescent boys’ literacy project, surely garnered me my youngest audience.

This new anthology represents my work within the sociocultural context in which it came to maturity, the downtown scene of the 1980s. A large, sprawling compendium of texts and documents, Up Is Up, But So Is Down is a scrapbook of an era. The interesting thing about that time in that place is that while there were surely many individual “scenes,” one could also truly speak in terms of an overarching downtown scene.

Of course, downtown New York was always the hotbed of Bohemianism and experimentation. By the time of my downtown, however, Greenwich Village no longer had any real significance in the equation. I’d say that the downtown scene I worked within was born largely of the convergence of the sixties East Village counter-culture and the genre-crossing SoHo scene of the seventies (even if that was really just a heating up of things that had started brewing in the sixties). While collaborations among artists, writers and musicians had a long history in New York, in my downtown the distinctions between who was what had blurred. My downtown was a stew.

I moved to the East Village from Brooklyn in 1979. I had found the perfect apartment to be a downtown writer in. It was a dark, gloomy first-floor tenement apartment on East 10th Street, just west of Tomkins Square Park, on the block with the Russian Baths, a Ukrainian Church, and the Boys Club, not to mention Carlo Pittore’s Galleria dell’Occhio, the mail artist’s window gallery. My apartment had a bathtub in the kitchen, a tiny water closet, crumbling walls and a ceiling that once ended up on my floor. At least I had my own toilet. Some buildings still had shared toilets down the hall.

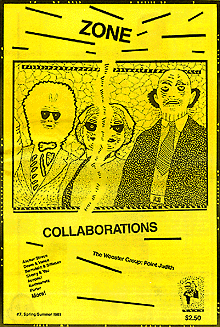

By this time I had been publishing my work in literary magazines for a couple of years and was also editor of my own magazine, Zone. I had moved to the East Village because all sorts of interesting things were happening there, and at age 23 I needed to be in the thick of it. Over the next eight years, which I’ll nostalgically declare the chronological heart of the downtown scene, things got out of control in all the best ways. New magazines and performance venues seemed to be launched every week. Writers and painters formed rock bands. Painters made performance pieces, writers made performance pieces, writers, painters and musicians collaborated on performance pieces. I started performing.

To read the rest, go here