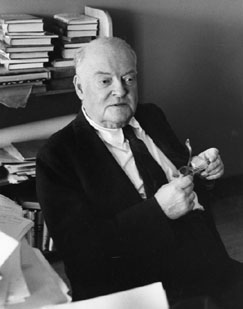

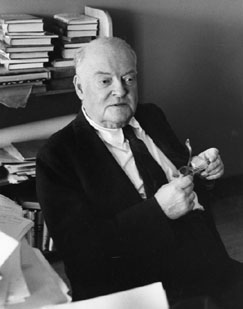

In between books I have to read for work, I’ve sneaked in a few pages of the two-volume Edmund Wilson set recently put out by the Library of America. It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that, when not defending Hemingway against his political critics or concluding that Intruder in the Dust “contains a kind of counterblast to the anti-lynching bill and to the civil-rights plank in the Democratic platform,” the man was a bit of a douchebag. And I say this as someone who enjoys some of his literary criticism. What’s particularly surprising is how dismissive Wilson is of mysteries.

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

You cannot read such a book, you run through it to see the problem worked out; and you cannot become interested in the characters, because they never can be allowed an existence of their own even in a flat two dimensions but have always to be contrived so that they can seem either reliable or sinister, depending on which quarter, at the moment, is to be baited for the reader’s suspicion.

If Wilson protests the detective story so much (as he points out, T.S. Eliot and Paul Elmer More were enchanted by the form), why did he bother to write about it at all? Should not an erudite and ethical critic recuse himself when he loathes a particular form?

It gets worse. If caddish generalizations along these lines weren’t enough, he returns to the mystery subject in the essay, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?,” written in response to many letters that had poured in from readers hoping to set Wilson straight. He dismisses Dorothy Sanders’s The Nine Tailors, openly confessing:

I skipped a good deal of this, and found myself skipping, also, a large section of the conversations between conventional English villa characters: “Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background,” etc.

Aside from the fact that Wilson, in failing to read the whole of the book, didn’t do his job properly, it never occurs to Wilson that Sayers may have been faithfully transcribing the specific manner in which people spoke or that there may actually be something to these “English village characters.” Here’s the full quote from page 57 of Dorothy Sayers’s The Nine Tailors:

“Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background. That’s right, Hinkins. Six in front of this tomb and six the other side — and have you brought those big pickle-jars? They’ll do splendidly for the narcissi….”

In other words, what Wilson has conveniently omitted from his takedown is Sayers pinpointing something very specific about how everyday routine, a fundamental working class component that seems lost upon Wilson despite his Marxism, leads one to disregard the fact that someone has died. Thus, there is a purpose to this conversation.

Yet this is the man being lauded on the back cover of the Library of America volumes as “wide-ranging in his interests.”

Wilson read mysteries for the wrong reasons. He saw trash only because it was what he wanted to see. Wilson’s incompetence is a fine lesson for contemporary readers. A book should be read on its own terms, and it is a critic’s job to try and understand a book as much as she is able to, reserving judgment only when she has fully read the book and after there has been some time to masticate upon the reading experience.

I disagree with Adam Kirsch’s recent assessment that “The best critics, like the best imaginative writers, are not right or wrong — they simply, powerfully are.” A critic, like any other human being, is often wrong, particularly when approaching a book with prejudgment or a fixed notion, such as Wilson did, of a mystery merely being about whodunnit. To avoid being wrong in this way, and to simply exert one’s opinion at the time of reading, requires as much careful reading and accuracy as possible, lest a great novel be thoroughly misperceived. It requires acceptable context and supportive examples. Wilson could not do this with mysteries and, if he is to be lionized, one should be aware that, when it came to Dorothy Sayers, he was no better than Lee Siegel in his tepid reading comprehension.

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding: