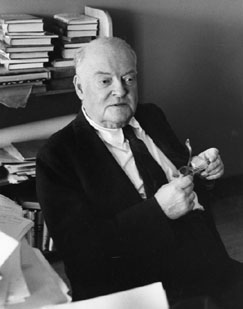

In between books I have to read for work, I’ve sneaked in a few pages of the two-volume Edmund Wilson set recently put out by the Library of America. It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that, when not defending Hemingway against his political critics or concluding that Intruder in the Dust “contains a kind of counterblast to the anti-lynching bill and to the civil-rights plank in the Democratic platform,” the man was a bit of a douchebag. And I say this as someone who enjoys some of his literary criticism. What’s particularly surprising is how dismissive Wilson is of mysteries.

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

You cannot read such a book, you run through it to see the problem worked out; and you cannot become interested in the characters, because they never can be allowed an existence of their own even in a flat two dimensions but have always to be contrived so that they can seem either reliable or sinister, depending on which quarter, at the moment, is to be baited for the reader’s suspicion.

If Wilson protests the detective story so much (as he points out, T.S. Eliot and Paul Elmer More were enchanted by the form), why did he bother to write about it at all? Should not an erudite and ethical critic recuse himself when he loathes a particular form?

It gets worse. If caddish generalizations along these lines weren’t enough, he returns to the mystery subject in the essay, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?,” written in response to many letters that had poured in from readers hoping to set Wilson straight. He dismisses Dorothy Sanders’s The Nine Tailors, openly confessing:

I skipped a good deal of this, and found myself skipping, also, a large section of the conversations between conventional English villa characters: “Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background,” etc.

Aside from the fact that Wilson, in failing to read the whole of the book, didn’t do his job properly, it never occurs to Wilson that Sayers may have been faithfully transcribing the specific manner in which people spoke or that there may actually be something to these “English village characters.” Here’s the full quote from page 57 of Dorothy Sayers’s The Nine Tailors:

“Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background. That’s right, Hinkins. Six in front of this tomb and six the other side — and have you brought those big pickle-jars? They’ll do splendidly for the narcissi….”

In other words, what Wilson has conveniently omitted from his takedown is Sayers pinpointing something very specific about how everyday routine, a fundamental working class component that seems lost upon Wilson despite his Marxism, leads one to disregard the fact that someone has died. Thus, there is a purpose to this conversation.

Yet this is the man being lauded on the back cover of the Library of America volumes as “wide-ranging in his interests.”

Wilson read mysteries for the wrong reasons. He saw trash only because it was what he wanted to see. Wilson’s incompetence is a fine lesson for contemporary readers. A book should be read on its own terms, and it is a critic’s job to try and understand a book as much as she is able to, reserving judgment only when she has fully read the book and after there has been some time to masticate upon the reading experience.

I disagree with Adam Kirsch’s recent assessment that “The best critics, like the best imaginative writers, are not right or wrong — they simply, powerfully are.” A critic, like any other human being, is often wrong, particularly when approaching a book with prejudgment or a fixed notion, such as Wilson did, of a mystery merely being about whodunnit. To avoid being wrong in this way, and to simply exert one’s opinion at the time of reading, requires as much careful reading and accuracy as possible, lest a great novel be thoroughly misperceived. It requires acceptable context and supportive examples. Wilson could not do this with mysteries and, if he is to be lionized, one should be aware that, when it came to Dorothy Sayers, he was no better than Lee Siegel in his tepid reading comprehension.

Huh — I listened to an unabridged audio version of The Nine Tailors years ago on a cross-country trip, and it was clear that Sayers was writing a novel of village life that happened to be disguised as a mystery. The solution to the mystery, while ingenious (and probably groundbreaking at the time), was a secondary pleasure.

Wilson didn’t “get” Lovecraft either.

It’s probably in there at some point, but Wilson also famously hated Tolkien, calling The Fellowship of the Ring “juvenile trash.”

Come on not everyone needs to love everything Ed. Besides if literary fiction sold even close to the way mysteries and other “genres” do they wouldn’t need champions. (hah, haha) I think the snobbery of literary writers and critics (much like the snobbery of poets towards prose writing) has to do with the sense of embattlement one gets from being not widely read, not necessarily understood, generally ignored.

Wait, not everyone thinks that Tolkien is clumsy and juvenile? That is more surprising than Wilson’s correct opinion of it.

I have tried, I really tried to appreciate Wilson and I have never found him anything but a tremendous bore.

About mysteries, they ARE essentially whodunits! Or are you going against your advise that a book “should be read on its own terms”?

No, Seriously, some of us kinda like Tolkien and don’t find his insights juvenile.

Hope the failed novel about nothing in particular is coming along swimmingly.

I’m afraid it may have been Bunny Wilson’s snobbery, rather than his great essays on such topics as Dickens, Wharton, Hemingway’s misogyny, Casanova’s old age, and Joyce, that allowed him to remain a revered figure in the Fifties and Sixties. Only one side of the Left’s populist/High Culture battles of the Thirties stayed respectable after the war, at least in literature; and it wasn’t the side that welcomed Hammett and Pohl but the side that was more easily co-opted by the CIA.

You know what else? “The Wound and the Bow” is an utterly pedestrian essay, mostly comprising plot summary, that’s had a pernicious effect on the use of Disease as Metaphor.

You know, Wilson does have value: critics like Wilson help fellow snobs avoid the hack books, whether they are juvenile and clumsy, but bestsellers. It’s a brotherhood that I like. Where Wilson failed is in his judgement that a mystery has no value. He just didn’t see it as value and didn’t allow anyone else to believe they had value. He was a hammer and everything else a nail.

Ooh, can we have an essay on Stanley Edgar Hyman next?

[…] a douchebag.” To be clear on this, I wrote “the man was a bit of a douchebag” and offered an argument supporting why I felt this to be the case. Nevertheless, I will inform the editors who hire me on a professional basis that Lee Siegel has […]

Edmund Wilson incompetent? ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha. Then again this is the INTERNET-dummyville.

Wilson is easily the finest American critic of the 20th century. Mr. Champion helps us chart the decline of the American intellect….and his own.

Here again we see the “narcissism of small differences…” at which Mr. Champion is champ.

To paraphrase someone’s comment, Edmund Wilson’s mission was to prove that he was the only adult in the room.

heres to bunny wilson

who set the table at a roar

was best at criticism

and always managed to score

and now its po mo polemic

and writers who can’t parse

farewell to edmund and his age

alas: we’ve now just farce

Wilson is a bit of a complicated person. If he was a snob at times, it harkened back to his days as a privileged youth, going to a fine prep school and then to study under Gauss at Princeton. He read voraciously, traveled all over Europe, Russia, Canada in addition to the US. But, he had a love for the common man, despite appearing snobbish at times. Consider his in depth study of the Iroquois Indians and his genuine empathy for them. I truly believe he was also a believer in integration and that all human races are equals. I would not consider him “boorish.”

Wilson tended to get carried away by charming and good looking younger women. Perhaps Anais Nin owed him her professional career for his overly enthusiastic reviews of her early works. Also, Wilson drank too much. If you read “The Fifties” and “The Sixties” you will see his thinking is often clouded by alcohol. But, I enjoyed reading these plus “Upstate”, the “Old Stone House” and a few of his other writings. I do not think you can truly call Wilson a snob after you see how he truly enjoyed mixing with the country people who lived around his beloved Talcottville Old Stone House.

The sad thing about wilsons snotty ( self admittedly absent and incompetent criticism ) of genre’s such as mystery, horror and fantansy, is that those genres have replaced the “serious” forms of his generation. younger reasers of wilson (if there are any) must be wondering if he was on some heavy druge, or just insane

He may be a snob, but that’s ok. I like critics with strong opinions, it would be boring, if there were no critics like him. When it comes to art, a little snobbishness is necessary, otherwise it would be pretty lame and wishy-washy. When you have taste (and I mean real taste, something elaborate, something to work on, not only consisting of “like it”, “not like it”) then there are things that you hate. And I like eloquent haters in criticism, they are entertaining and important.

This article sounds as if the person who wrote it felt offended by Wilson’s criticism. That’s ok, but it’s not ok to call someone like Wilson incompetent and bash upon him in this way. He has done so much for literature, he wrote some very fine pieces and he had taste. Not your taste, not mine, but his own. So you have to accept, that he had opinions that you don’t like on subjects which are important to you.

And, seriously, although I like Agatha Christie and this whole genre: it is not high literature when you compare it with people like Dostoevski, Shakespeare, Cechov or Proust. It is pretty good entertainment. But literature, for me, is more than that. It is deeper, richer, more complex, it tells me something about life, about psychology, about philosophy and the way we perceive things and if it is really really good literature it may change our perspective on many things. Last but not least, in literature language and style are very important things. For Christie language is just the means to tell a good story, for Proust or other writers, it is more, it represents the personality of the writer with all his idiosyncrasies, it is the medium of his art, it is itself art. All these things have no importance for Christie, she just wants to tell her story, she wants to present a mystery and the solution to it, for entertainment (and in this respect, she was extremely talented).

I know, it always sounds arrogant, when someone distinguishes between mere entertainment and art, but I think, that it is right and justified to distinguish between these two forms. Of course, in between these two, there is a grey area, there is a mix, especially in modern times. But I think it’s a failure to completely give up these borders.

RE Gorundium

Love your insightful words about the differences between mysteries and literature. I’m glad there are admirers of both, and won’t label those who prefer literature as snobs. Some people read for entertainment, others prefer to be moved and challenged with stories that convey truths about the human condition, with masterful use of language.

Gorundium:

The difference between literature and entertainment, that’s a worthy topic for a critic, so much so it’s kind of a cliche of critical literature. Who is to say what is or what is not, entertainment. You may say you read Proust or Dostoievsky to gain insight on the “human condition” in order to engage with writers whose fiction is self consciously dealing with philosophical themes, yet this is still fiction it’s not producing concept their aim is still to create an alternate world and to tell a story and in a way to entertain, it entertain in that it seeks to gain our attention in a way that is directed toward anything “useful” in the common sense of the word. It entertain in the sense that whatever level of realism and reflection they contain they distract us (literally) from our day to day reality. This is what entertainment is.

So maybe they have another goal, they are reflecting upon social structures, political issues of the day, metaphysical or theological concept, great moral question, yes it’s true, Proust, Dostoievsky, Dickens, Victor Hugo, George Elliot, Balzac, Tolstoy all the great luminaries of the 19th century were writing to impact society and make their contemporary think about their condition. Yet one of the most influential books of the era is Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, certainly not a literary masterpiece but a huge popular success and one that contribute to awake public consciousness against slavery. I am not saying it lead to its abolition but it’s political influence without doubt was huge, and arguably more so than any of Dostoievski (who never wrote for an elite) or Tolstoy, or even Dickens or Hugo who wrote similarly popular and political minded books. In Hugo’s case for exemple Les Misérables takes part of its inspiration in Les Mystère de Paris a hugely popular serial that is not in any way comparable to Hugo’s titanic masterpiece in terms of literary achievment, but was arguably a much more influential books on the politics of 19th century France (and in even Europe since it was widely imitated and at somepoint every major cities in Europe had its “mystéres”). So where is that other quality that supposedly separate “literature” from “entertainment” since entertainment can also engage with serious themes even when it’s not particularly well written, and may in fact be more effective as a vehicle a for wider political or moral ideas and questions than much more sophisticated (and I agree worthy in an aesthetic or even intellectual) piece of literature.

One answer, maybe the most evident, would be, it’s in the quality of the writing, in the way the writer use language, in its style that showcase his personality, that shape his worldview and to some extent how we will respond to it. It’s in the way in makes us feel, in the way he may challenge our expectation both in terms of narrative craft and in lingusitic turns. But then we are entering the realm of art for art sake. And Although I would agree that it may be a much deeper, much more sophisticated pleasure than that of just having a story told, is it not in some way an entertainment? how does it differ? how does the sensual pleasure one took in reading a beautiful piece of writing is that different than the excitement of a good story? It’s not. It is entertainment, it is equally a leisurely activity, something we usually do in our spare time (unless you are a teacher of literature, and editor or a literary critic). I do think Les Misérables is a much better book than Les Mystéres de Paris or Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but it’s still an entertainment in many ways, one that enjoy because I happen to belong to the kind of public that read classic literature, one that has studied literature and understand the codes through which so called literary fiction appeals to it’s reader. But it’s no less an entertainment than a so called cosy murder mystery.

Back to Agatha Christie, now. It’s true she is no Proust, her prose appears to be, well, prosaic. We don’t read her for the beautiful cadence of her sentences, or her evocative imagery (although she does have her moments on both these accounts, and she is, at her best, a rather witty writer in her dialogues and she shows a great sense of comedy in her description). But is it purely “functionnal” though? I mean she does not just tell a story, the point of her wodunit is to manipulate us into dead end while also giving us clues to resolve the mystery, she does this through her mastery of narrative point of view and ellipsis, that in itself is worthy of a literary appreciation (because narrative art, in the sense of how you built a plot, and how you transmit to the reader is clearly part of literature as an art), she does it by playing with stereotypes and expectations linked to stereotypes (therefore she rarely pander to simplistic clichés in her best book it often goes with a kind of distanciation that can, again, be rather sophisticated), and she does so through language. Words in a murder mystery (any murder mystery) cannot be used randomly, they have to be carefully, the sentence carefully built, because they are integral to the labyrinth of the plot. Also the reasons why Agatha Christies books are so successful is precisely because they are not just about the “mystery”. Granted she is not a deep psychologist, but she does give insight about her characters life (both interior and exterior) that actually gives them enough depth for them to carry our interest. Contrary to the much used cliché by those who never really read her, her books are not mere puzzle, they actually have a human interest, the victim is often a quite complex figure and so are the murderers, they are very rarely integral monster and while the end shows the victory of good and order over crime and evil (in some way) there is a kind of moral grayness in Christie and yet it is never relativistic. Because this melodramatic morality (and I am not using melodrama as derogatory term here but rather as, like the great critic and academic Peter Brooks has shown, a mode of excess and heightened morality in response to the perceived chaos of a post-sacred world) is integral to the success of the whodunit. Not just because they are reassuring, in fact they are ambivalent, they reassure and frightens us at the same time. The very seriality of the books suggest that there is never a definitive victory, that there can’t be in fact a definitive victory. The ordinariness of the killer, often someone well established in society someone above all suspicion is also a way to destabilize the sense of order the books is otherwise trying to maintains, this makes the murder mystery a rather fascinating genre when you take it seriously.

I am not suggesting Agatha Christie is an unknown George Elliot, she did write inside a formulas, but it is a formula that she managed to renew and expand, so much in fact that she does not pale in comparison to her distinguished predecessors Poe, Wilkie Collins, Leroux or Conan Doyle. And that is not a small achievement, her best books such as And then there were none, Five Little Pigs, Crooked House, The Hollow, Murder on the Orient Express, Murder at the Vicarage, A Murder is Announced, Death on the Nile, Roger Ackroyd are not just shallow and fugitive entertain they actually sustain re-reading and close reading. They may not have the sophistication of Proust or the profundity of Dostoievski (but nobody is claiming this mainly because it would be an absurd and shallow comparison that does not say anything remotely interesting on either christie and the murder mysteries or these “great canonic novelists”), they offer a complete mastery of the genre in which they are written, they go beyond the expectation in fact and often manage to be innovative inside the genre formula, and they offer convincing and engaging and even disturbing character. Her prose is clear but is not as transparent as one may think, it has its poetic moment (all the more effective due to their infrequency) and is often wity with an effective satire of a certain english society of her time. I don’t find it cosy or complacent toward this society, in fact she often shows the hypocrisie and short sightedness of such people and in a work like The Hollow for example, Christie shows herself a really nuanced psychologist. In short yes this is entertainment, but the very fact that it endures should be enough to warrant more caution than dissmissing it out of hand.

Now to criticism. I am not saying there is no value, no good or bad, I do think there are good and bad books, I also think this should never be examined in terms of genre, because usually what the critic display (as does Wilson in his essay on Tolkien or Murder Mysteries) is his own prejudice and his failure to actually engage with the works in their own terms. What insight does Edmund Wilson gives us on the murder mystery in his review? what insight does he give us about the great literary work he admires in comparison? almost none. He actually do not go beyond a simple “I don’t like it, I think it’s shit”. He does not give any literary analysis (granted he probably did not have the space to do that in this essay, but I am pretty sure had he be given that space it would have amounted to a summary of the plot a few derogatory remark on how it’s simplistic and stupid and how the style is trite, with very few effort in explaining what that triteness might be). He does not even really try to understand this “bad literature” in his view appeal to so much people, his explanation for the readership of detective story is actually simplistic and demonstrate his poor knowledge of the genre and a poor understanding of its working (in Christie, and in the golden age detective fiction in general) the murderer turns out to be an ordinary person (granted his ordinariness may conceal something else, but most of the time he is ordinary and even likeable) and yes the end of the novel “fixes” the guilt in some way but it has highly unstable since it all has to start again. Also it is clearly not the case in An Then There Were None or even Murder in the orient express. The genre is interesting because it has a capacity to renew itself, to break it’s own convention, that is also a pleasure that is rather literary.