(This is the third of a five-part roundtable discussion of Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia. Additionally, Spiotta will be in conversation with Edward Champion on July 20, 2011 at McNally Jackson, located at 52 Prince Street, New York, NY, to discuss the book further. If you’ve enjoyed The Bat Segundo Show in the past and the book intrigues you, you won’t want to miss this live discussion.)

Additional Installments: Part One, Part Two, Part Four, and Part Five

Lydia Kiesling writes:

First of all, thanks, Ed, for putting this together and for giving me a reason to read something new.

Levi, I was interested to hear your thoughts about Nik: specifically, that he can in no way be considered an artistic success. It actually never occurred to me that he could be seen as anything but, since my rather rudimentary sense about what makes an artist is largely based on (a) being really weird and (b) creating a body of work. Item (b) is crucial here. I’m not saying Nik Worth is Emily Dickinson, but I think there is always something compelling about a person who puts in such an astounding amount of work for a limited or nonexistent audience, at the expense of health, happiness, and personal relationships (Nik also fulfills another category in being a dick and causing his family heartache). Of course, the fact that the only judgments of Nik’s musical output come from his sister and niece (they laugh about this over pink champagne) is suspect. That said, the nature of Nik’s work — the cross-referencing, the album art, the storylines — takes him out of traditional musicianship and cleverly elides the necessity of getting a ruling on the merit of his output. If someone spent thirty years ruining his health and his sister’s finances writing a twenty-volume novel sequence, we have to see the novel to know whether it was “worth” it (see what I did there?). But in Denise’s descriptions of Nik’s output and the alternative reality he has created for himself, he’s more of a performance artist than a musician. It’s a convenient way of leaving us (or me, anyway) unable to decide whether Nik is a genius or what. I’m sort of on the “genius” side, but I guess it doesn’t matter so much.

While I’m on your comments, Levi, I was also intrigued by your Byron-Augusta reference. I don’t have siblings. So I don’t know what’s what about brother-sister relationships. But Denise and Nik have something that seems more like an unsatisfactory romantic relationship, without sex, and with one partner withholding commitment, household contributions, etc. As another panelist pointed out, Jay fills the sex niche. The fact that Jay is, in and of himself, not your average sex-niche-filler — for one, he has very specific, effete interests that he and Denise actually share — is, to me, a testament to the overwhelming power of the sibling relationship here. Which is not to suggest that Denise should just be happy that she has a man. But Jay seems like a good fit. How often to you meet a guy with an unavailable 1950s film in the trunk of his car, a film that you actually want to watch too? (Maybe it’s a Los Angeles thing.) So this Jay is kind of a character and maybe a catch, but she’s just not that into him. We don’t know what Denise is like when she is in love — with the father of her child, with her second husband. We only know what she is like in love with Nik (she’s “Little Kit Kat, the wonder tot”).

While I’m on your comments, Levi, I was also intrigued by your Byron-Augusta reference. I don’t have siblings. So I don’t know what’s what about brother-sister relationships. But Denise and Nik have something that seems more like an unsatisfactory romantic relationship, without sex, and with one partner withholding commitment, household contributions, etc. As another panelist pointed out, Jay fills the sex niche. The fact that Jay is, in and of himself, not your average sex-niche-filler — for one, he has very specific, effete interests that he and Denise actually share — is, to me, a testament to the overwhelming power of the sibling relationship here. Which is not to suggest that Denise should just be happy that she has a man. But Jay seems like a good fit. How often to you meet a guy with an unavailable 1950s film in the trunk of his car, a film that you actually want to watch too? (Maybe it’s a Los Angeles thing.) So this Jay is kind of a character and maybe a catch, but she’s just not that into him. We don’t know what Denise is like when she is in love — with the father of her child, with her second husband. We only know what she is like in love with Nik (she’s “Little Kit Kat, the wonder tot”).

What else? I get a kick out of the fact that we are discussing this remotely (and that when I received the first response, I was in the middle of uploading Facebook photos). I’ve never met you fellow readers. I Google you to see what you’re about, and I owe the Internet to my very presence on this panel. Like Ada, and later Denise, I identify “audience” (such as it is) in page counts, or in disembodied comments, which could, for all I know, be left by one intrepid, shape-shifting troll. I think Spiotta deftly invites us to consider the new confusion about fame and art/not-art in the Internet age, without belaboring the point. She gives a couple of sample inane comments on her daughters’ blog, for example, and for me these conjured up a decade of confusion and anxiety and gratitude to the Internet. Nik’s work and persona make it onto the Internet and generate interest, but people who use the Internet, or who try to cultivate their own small fame plant, know how little his 5,000 YouTube hits might turn out to mean in the long run. He hasn’t been made. He’s just been archived in the digital cabinet of curiosities (did I steal that phrase from Denise?).

Darby, I love your comments about Stone Arabia as a non-postmodern novel with postmodern stuff in it. As I read, I kept thinking that I should feel as if I were deep in Paul Auster territory (frustrated, scared). Despite its frames and edgy preoccupations, the novel felt like a good old-fashioned look at relationships. The plot and the external details of the characters’ lives were, I thought, sort of incidental. I didn’t buy the trip to Stone Arabia — it didn’t feel necessary to me. The fun-uncle dad and Ada’s married lover are just stand-ins, Daddy Issues props. What really moved me was Spiotta’s ability to transmit a feeling that might be your own — sadness over a parent, anxieties about memory and loss. I have to say I did a little crying over this novel (the crying factor is not the only thing this novel shares with some episodes of This American Life, incidentally). Most of all, I immediately recognized the sense of yearning, what Spiotta calls want, that she transmits through Denise. I was amazed at the way she was able to recreate the humming-wire feeling of adolescence — the way you want to destroy your ears with loud music, and be beautiful, and do something. And maybe, because I read this book, this is why I had two beers, put on headphones, and revisited some seminal tracks of my high school years the other day.

Darby, I love your comments about Stone Arabia as a non-postmodern novel with postmodern stuff in it. As I read, I kept thinking that I should feel as if I were deep in Paul Auster territory (frustrated, scared). Despite its frames and edgy preoccupations, the novel felt like a good old-fashioned look at relationships. The plot and the external details of the characters’ lives were, I thought, sort of incidental. I didn’t buy the trip to Stone Arabia — it didn’t feel necessary to me. The fun-uncle dad and Ada’s married lover are just stand-ins, Daddy Issues props. What really moved me was Spiotta’s ability to transmit a feeling that might be your own — sadness over a parent, anxieties about memory and loss. I have to say I did a little crying over this novel (the crying factor is not the only thing this novel shares with some episodes of This American Life, incidentally). Most of all, I immediately recognized the sense of yearning, what Spiotta calls want, that she transmits through Denise. I was amazed at the way she was able to recreate the humming-wire feeling of adolescence — the way you want to destroy your ears with loud music, and be beautiful, and do something. And maybe, because I read this book, this is why I had two beers, put on headphones, and revisited some seminal tracks of my high school years the other day.

To add one more name to the mix, Sam Stone: original bassist for the Demonics, ruined veteran in the John Prine song of the same name. Take it or leave it.

Levi Asher writes:

I like your criteria for what it means to be an artistic success, Lydia. When you put it that way, I can’t disagree. But yes, I was surprised to find Ed focusing on the question of whether or not Nik had artistic integrity, because it had never occurred to me that anybody could be impressed by Nik’s career — and I mainly mean this in relation to what the characters in the book must feel, not so much to what readers can feel. Even if we can be impressed by Nik (though, like Darby, I wasn’t — been there, done that, was embarrassed about it), I still feel sure that Denise, Ada, and their Mom were not proud of Nik. And most importantly, Nik wasn’t proud of Nik. Maybe some of Nik’s girlfriends were for a few minutes. Anyway, Roxane’s reference to the TV show Hoarders hit it exactly right for me — I was planning to bring the same comparison up. Nik is a “funny obsessive,” like the people we gawk at on Hoarders, and that’s what’s sad about his YouTube popularity.

A couple more things: I’m glad Lydia said she doesn’t buy the trip to Stone Arabia, and I’d like to take this further — did that trip across the country even take place? It seems unreal. I wonder if the author put that “trip” there (and named the book after it, sans any explanation or justification) as a signal that this narrator is more unreliable than she may otherwise seem. What do all of you think the book’s title is supposed to mean?

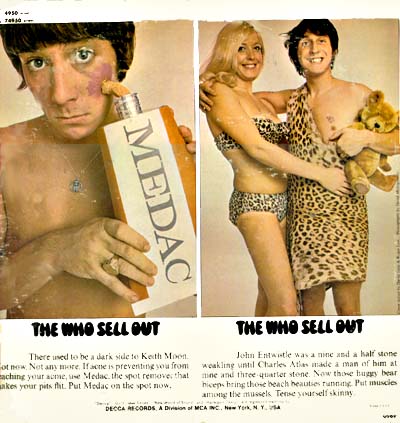

Finally, to answer Darby’s question about the album cover: well, I think Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols must be the reference point for an album cover with titles composed of kidnapper-style cutout letters. An ironic reference point, since this album helped introduce punk rock to the world (and thereby helped to kill Nik’s earnest mid-1970s musical innocence).

Edward Champion writes:

I’m fascinated by Levi’s obstinacy here, which I now feel compelled to rectify in light of Roxane’s sharp observations about Nik being “a blogger before there was blogging.” Levi seems to be pushing the notion that artistic integrity is inexplicably connected to commanding the respect of an audience. To which I reply: is the respect of one person (in this case, Denise) enough to justify artistic integrity? In other words, what kind of artistic integrity are we talking about here? You’ll note in my opening salvo that I mentioned the “right side” of artistic integrity. And since Diane has brought up the abominable Lee “Lux” Smith — the increasingly extinct (and banned?) incandescent who is described by Denise as having “long lurked at the periphery of the various Los Angeles scenes,” who has “always had his icky fingers in an anthology or documentary,” and who started off as a songwriter, penning a few jingles for a group called the Ginger Jangles — I’m wondering if Lux might have ended up on the “right side” of what I’m going to style “exclusive artistic integrity” if he had not pursued money or had not been so content to crown crap as hype (such as the “uncomfortably handsome singer from Canada”).

I’m fascinated by Levi’s obstinacy here, which I now feel compelled to rectify in light of Roxane’s sharp observations about Nik being “a blogger before there was blogging.” Levi seems to be pushing the notion that artistic integrity is inexplicably connected to commanding the respect of an audience. To which I reply: is the respect of one person (in this case, Denise) enough to justify artistic integrity? In other words, what kind of artistic integrity are we talking about here? You’ll note in my opening salvo that I mentioned the “right side” of artistic integrity. And since Diane has brought up the abominable Lee “Lux” Smith — the increasingly extinct (and banned?) incandescent who is described by Denise as having “long lurked at the periphery of the various Los Angeles scenes,” who has “always had his icky fingers in an anthology or documentary,” and who started off as a songwriter, penning a few jingles for a group called the Ginger Jangles — I’m wondering if Lux might have ended up on the “right side” of what I’m going to style “exclusive artistic integrity” if he had not pursued money or had not been so content to crown crap as hype (such as the “uncomfortably handsome singer from Canada”).

Diane suggested that Stone Arabia was “about loving somebody who is incapable of returning that love.” Well, what better description is there of the fan’s temperament? What’s interesting is that Spiotta doesn’t quite get at the issue of how the artist must smile and nod when presented with a fan’s unabashed (and uncurated) ardor. But I’m going to go out on a limb and offer the theory that Spiotta’s “exclusive artistic integrity” — which all of us are capable of, even though it’s become increasingly harder to find outsider art in an age in which nearly every phenomenon goes viral or becomes a sensation “known by all” — is what ultimately puts an elaborate response to art (which Nik’s Chronicles may very well be, as some folks here have already mentioned) on the same footing as art. I think this fits in with Lydia’s idea of being impressed by “a person who puts in such an astounding amount of work for limited or no audience.” (And, Lydia, isn’t that just what we’re doing with our respective efforts to read the entirety of the Modern Library 100? I’m now raising the champagne flute in deference to another quirky soul!) I think Our Man Birnbaum is smart to bring up the idea of how we can even complete the prospect of reading or writing about a book. How many of you feel that the act of artistic engagement has become almost a full-time job these days? And do you think Nik has created the ultimate solution for this? I guess I have more sympathy for Nik as a “funny obsessive” than Levi does. Keep in mind that Nik is creating these personae in order to survive — even though his own diminishing returns swell like gout.

I also feel that I must intervene in the apparent “disagreement” between Bill and Diane. Why can’t Jay live “in the moment” (there’s a phrase that defines polyamory for you) and be a fill-in? Keep in mind that you’re talking to a guy who spent thirteen formative years in San Francisco. I saw quite a lot of this type (and even slept with a few): the person who throws herself into an affair or an unusual sexual arrangement (and Jay does fulfill the role of a secondary, doesn’t he? who do you think Denise’s primary partner is in this polyamorous relationship?) that feels “different” or “alternative” from the apparent norm, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect what’s right for that person. Remember, this is “an affair without urgency or agenda, it seemed.” It seemed! Two key words suggesting that Denise knows exactly what she’s getting into (who wouldn’t with Thomas Kinkade, the most unsubtle American artist, involved?), but doesn’t wish to be honest. What does Denise really want? I mean, she tells her own daughter, “So you are eighteen, on quaaludes and dressed like a whore — I don’t have to explain that this often led to a less than fulfilling outcome for young women.” What we’re pussyfooting around here in this discussion is how Denise’s relationship with news headlines and photos is just as problematic. Not especially fulfilling, yet very much an “outcome” rather than something that can be changed. Or can it? Darby has brought up Jennifer Egan (it was bound to pop up), but, since we’re establishing comparisons with last year’s books, I’m almost tempted to compare Denise’s journal against Patty Berglund’s “Mistakes Were Made” in Freedom. To my mind, this seems a more fitting parallel, if only to see how Denise is both oblivious to the root cause while very aware that memory might very well provide some pivotal context for it to emerge, whereas Patty is ostensibly ordered to write the damn memoir by her therapist. Is a greater cure for the unfulfilled life likely to emerge from active straightforward writing? Perhaps. But what happens if you’re living in the shadow of a brother who will always write more “elaborately” than you? If Denise really is the book’s emotional core, as Darby suggests, then I’m wondering the degree to which Denise’s legitimate feelings can be asphyxiated by a bustling culture of commentary — to which all of us here are quite pleasantly guilty!

I also feel that I must intervene in the apparent “disagreement” between Bill and Diane. Why can’t Jay live “in the moment” (there’s a phrase that defines polyamory for you) and be a fill-in? Keep in mind that you’re talking to a guy who spent thirteen formative years in San Francisco. I saw quite a lot of this type (and even slept with a few): the person who throws herself into an affair or an unusual sexual arrangement (and Jay does fulfill the role of a secondary, doesn’t he? who do you think Denise’s primary partner is in this polyamorous relationship?) that feels “different” or “alternative” from the apparent norm, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect what’s right for that person. Remember, this is “an affair without urgency or agenda, it seemed.” It seemed! Two key words suggesting that Denise knows exactly what she’s getting into (who wouldn’t with Thomas Kinkade, the most unsubtle American artist, involved?), but doesn’t wish to be honest. What does Denise really want? I mean, she tells her own daughter, “So you are eighteen, on quaaludes and dressed like a whore — I don’t have to explain that this often led to a less than fulfilling outcome for young women.” What we’re pussyfooting around here in this discussion is how Denise’s relationship with news headlines and photos is just as problematic. Not especially fulfilling, yet very much an “outcome” rather than something that can be changed. Or can it? Darby has brought up Jennifer Egan (it was bound to pop up), but, since we’re establishing comparisons with last year’s books, I’m almost tempted to compare Denise’s journal against Patty Berglund’s “Mistakes Were Made” in Freedom. To my mind, this seems a more fitting parallel, if only to see how Denise is both oblivious to the root cause while very aware that memory might very well provide some pivotal context for it to emerge, whereas Patty is ostensibly ordered to write the damn memoir by her therapist. Is a greater cure for the unfulfilled life likely to emerge from active straightforward writing? Perhaps. But what happens if you’re living in the shadow of a brother who will always write more “elaborately” than you? If Denise really is the book’s emotional core, as Darby suggests, then I’m wondering the degree to which Denise’s legitimate feelings can be asphyxiated by a bustling culture of commentary — to which all of us here are quite pleasantly guilty!

To briefly return back to the “Ada” dance that Levi and I were involved with, I’ll see your Ada Lovelace and raise you Nabokov’s Ada! With Nabokov, you’ve got some reliable incest, a hundred years of history, and a manuscript contained within a book. Fun for the whole family! Did the Stone Arabia trip actually happen? Well, do you speak Stone Arabic?

Darby Dixon writes:

Finally, to answer Darby’s question about the album cover: well, I think Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols must be the reference point for an album cover with titles composed of kidnapper-style cutout letters. An ironic reference point, since this album helped introduce punk rock to the world (and thereby helped to kill Nik’s earnest mid-1970s musical innocence).

I’ve obviously totally outed myself as not having a punk rock background, pre- or post-popularizing, yes? The red in that cover is now the red in my face.

Bill Ryan writes:

Levi briefly touched a question I wanted to ask:

How do we take the narrative interludes that break up the Counterchronicles? Are they from the some omniscient presence who drifts over Denise’s shoulder? Denise’s Id? The way they literally interrupt sections of the book, the jarring quality of being pulled out of the first-person “looking back” and tossed into a third-person “present” — is this “reality” as Denise would prefer we all stick to? Or is this all another rabbit hole within Nik’s Chronicles? It struck me as odd that we’d begin with Nik’s letter, then never once step back into the Chronicles.

It seems like the author calls so much attention to the act of making art — that the vast majority of the book is neatly sectioned off as pieces of “art,” whether diary-style Counterchronicles or those odd, ordered “permeable events” — but then the narrative sections are just “there.”

I’d guess that I’m sniffing at the wrong scent on the wrong tree in the wrong forest, but still, it caught my attention.

Darby, at least you have the stones to admit your lack of punk. I spent the majority of my high school and early college years pretending I’d lived with a permanent sneer during the Whitesnake and the Damn Yankees years, and loved (or even knew about) the Dead Kennedys and Black Flag.

On the Jennifer Egan note, I’ve a plainer question for people in the know: to what degree can/does the publisher dictate how much Egan-ness (or, for another example, Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close) can go into a book? I’d guess that, relatively speaking, those sections that require the PowerPoint presentations or photographs (or even blank pages!), anything that isn’t simply text, would cost more to produce — if for no reason other than that these sections take up space where words would traditionally go. Would someone with less clout than a Jonathan Safran Foer or a Jennifer Egan get away with inserting pictures or lines and graphs or a silly drawing of a kitty cat in a “traditional” novel? Case by case, I’m guessing, of course. But I wondered if the author had wanted to put more of the Chronicles into the book, if her editor would’ve “gently persuaded” her to stick with text only?

On the Jennifer Egan note, I’ve a plainer question for people in the know: to what degree can/does the publisher dictate how much Egan-ness (or, for another example, Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close) can go into a book? I’d guess that, relatively speaking, those sections that require the PowerPoint presentations or photographs (or even blank pages!), anything that isn’t simply text, would cost more to produce — if for no reason other than that these sections take up space where words would traditionally go. Would someone with less clout than a Jonathan Safran Foer or a Jennifer Egan get away with inserting pictures or lines and graphs or a silly drawing of a kitty cat in a “traditional” novel? Case by case, I’m guessing, of course. But I wondered if the author had wanted to put more of the Chronicles into the book, if her editor would’ve “gently persuaded” her to stick with text only?

Apologies for drifting off into hypotheticals, but I was interested in the push-pull of the actual business decisions and how they reflect the “vision” of the artist. Like if we would have benefited from seeing more of the Chronicles, and the author’d created the work, is this a case where multimedia, or even ebooks, would be a better medium for the story? Would it be tacky to add “to see more of Nik’s art, go to www.StoneArabia.com”?

Paula Bomer writes:

I’m getting into the discussion late and honestly was unable to read everyone’s responses — which I plan to do later — but I wanted to just give my few reactions to the book itself and then to the few responses I was able to read before the week was over.

I agree very much that this book is about Denise primarily, and that Nik is her obsession, but frankly, we learn very little about him and only see him through the eyes of others.

I found the first half of the book slow going but was won over with the second half. I realize Spiotta — in many ways, with the idea of the Chronicles, Ada’s film, her Counterchronicles, etc. — is trying to examine storytelling, truth, and memory. I found the most compelling parts to be the first person Denise, writing the Chronicles — and the small framing device of third person, although symbolic, almost not necessary. For one, the voice is exactly the same. Secondly, I got confused and the payoff — when I figured out what she was doing — didn’t feel huge.

I wondered about the whole chewing on purity and authenticity in art — obscurity vs. well known, impenatrable music; Nik’s experimental style, the ridiculousness of “Soundings” (those were funny; I find that parts of this book are very slyly mocking). Because Spiotta clearly wants an audience. And as someone else here mentions, this book, despite all of its framing, is a conventional, realistic tale of a family. And I like that. I like that much more than the framing, just as I generally like more-or-less conventional pop music. (I’ve been listening nonstop to PJ Harvey’s new record about World War I: here is a woman who does whatever she wants, with no real regard for stardom, and has a real career anyway. She’s a successful Nik, a less “fuck you” Nik.) Compare this with Laurie Anderson, who I loved in high school. Can we talk about how many people, and not just myself, grow out of the novelty of “boundary pushing” or people trying to do something different and “new”?

I wondered about the whole chewing on purity and authenticity in art — obscurity vs. well known, impenatrable music; Nik’s experimental style, the ridiculousness of “Soundings” (those were funny; I find that parts of this book are very slyly mocking). Because Spiotta clearly wants an audience. And as someone else here mentions, this book, despite all of its framing, is a conventional, realistic tale of a family. And I like that. I like that much more than the framing, just as I generally like more-or-less conventional pop music. (I’ve been listening nonstop to PJ Harvey’s new record about World War I: here is a woman who does whatever she wants, with no real regard for stardom, and has a real career anyway. She’s a successful Nik, a less “fuck you” Nik.) Compare this with Laurie Anderson, who I loved in high school. Can we talk about how many people, and not just myself, grow out of the novelty of “boundary pushing” or people trying to do something different and “new”?

I agree this book is as much about memory as it is about middle age: how we feel our lives slipping away, how Denise’s mother’s mind is slipping away. I was really moved by the way Denise takes her mom’s medicine, and fears her own memory loss, because of her mom’s illness. This is the exact same thing going on with me. My mother has severe dementia and I keep thinking I’m developing it. Which brings me to the intense bonds of family that this book is also about. Nik became all that Denise had because of the loss of her father and her mother working nonstop. And, to me, that is the ultimate tragedy of the book — not being able to move on because you never had enough. Someone mentioned that Jay is a lukewarm fuckable Nik. That’s an interesting point. Denise can’t have a healthy relationship — a real committed one — because she committed to Nik. I see these types all the time. They make all sorts of excuses about why they aren’t in healthy long-term relationships, but it’s often as simple as not being able to break with their primary families. I never had a wedding, but the symbolism of a father “giving away” a daughter isn’t just a symbol.

Lastly, I like how people mention the reality of their own lives coloring their reactions to certain aspects of this novel. I recently went through a massive revision to try to make an editor happy. I haven’t elevated the obscure outsider art since my teens or maybe my twenties. And, even then, I didn’t elevate it much. But so many people do. It’s an interesting issue with art, but, as I believe, one that I believe is secondary to the human issues in this book.

Regarding The Ontology of Worth, whether Nik’s work is worth anything, the Fakes, and the question of authenticity in relation to Nik’s work (in particular the Fakes phase), I truly feel that these are questions that Spiotta leaves unanswered for a reason. I don’t believe she thinks there are any answers. And if this is the case, I agree with her for the most part.

Lastly, people have commented on the Stone Arabia ending/title issue. I agree that it seems slightly off, but I read it as a not-so-subtle (and I love how not-so-subtle much of this book is) way of having Denise deal with her grief and sadness about the love of her life (Nik) by projecting her emotions elsewhere. She grieves through the news, and even, God bless her, the Lifetime Movie Network, which I obsessively watched — meaning six hours a day — after my dad died. So it works for me on that level, even if it feels a bit forced. Grief makes us do strange things. If life is stranger than fiction and fiction has its own rules, perhaps this can be too lifelike, feeling slightly off in the land of fiction.

Also, does anyone want to chime in about the significance of Stone Arabia? Historically, it was a famous spot during the Revolutionary War. But is Stone Arabia’s obscurity part of its importance? That’s a good metaphor for the book, I think.

Darby Dixon writes:

“I’m not familiar with Spiotta. So I did not know what to expect from this book. But I found it very timely. I read Nik as a blogger before there was blogging…”

That, Roxane, is an awesome insight/reading, which prompts my own incredibly half-cocked response. Is this an apropos place to mention that Facebook was launched in 2004? Facebook itself stands firmly against the kind of identity-manipulation games that Nik plays through his Chronicles. Video killed the Radio Star. Mark Zuckerberg killed Nik Worth.

Flash back to the Net (or your local BBS scenes or whatever) in the late ’80s and ’90s (and however further back it went; yes, I was young when I first stumbled into it at speeds nearing 300 baud), when it was possible to be whomever or whatever you wanted to be. You could recreate your identity from whole cloth for an active audience of anyone technologically elite enough to join in.

Today, that model of identity has lost. We demand the truth about you (far be it for you to be more complex than you need to be, James Franco, cough cough) and we’re tying it all up into any available social network. What you are is the sum of all the actions you take online. Nik is a relic — if he tried to do the Chronicles as a Net piece, complete with invented reviews and reviewers, he’d eventually be outed, labelled a fraud, and run out of cybertown. (Is there a band working today that doesn’t have some modest thread of legitimate authenticity in their relationship to the world?) Not that it isn’t or couldn’t (or shouldn’t) be possible to do that today. I suspect there’s still a chance one could spend the time required to make an alternate life seem real. But.

This is where I begin to question and probe my own interest in Denise as the emotional core of the book. From this angle, she reads as a full subscriber to the post-Facebook model of identity, authentic, honest, sincere in her presentation of her identity to the world. And, yes, that may have always been the mainstream model all along. She is the future, and she desires the comfort of a future in which the people on the television are real people with real problems (problems that she could, in theory, help solve). She desires a future in which she is nothing but herself, her real self, and her fears of senility or dementia play against that. A sick mind that gets it wrong would interpret her to be more perilously close to being like Nik than she might like. (Though he does what he does for his own reasons, at least). Is it ideologically telling that I used the word “wrong” like that? Am I revealing my own issues with sincerity? In reading Denise as someone unable to be anybody other than who she is?

Here we have Nik, a musician who has devoted decades of his life (1970s-2003, a time period that intriguingly matches how long it took Brian Wilson to get around to

Here we have Nik, a musician who has devoted decades of his life (1970s-2003, a time period that intriguingly matches how long it took Brian Wilson to get around to  Would we be more satisfied accepting art on its own emotional terms? That’s a big question too. Because just look at the serious grief Denise offers in response to the news cycle, the ostensible “reality” that she feels compelled to confront. She can’t even name Lynndie England as she takes in the Abu Ghraib photos, but, much as many (including Nik) speculate on Nik’s character, she finds herself fixating on England’s “storm chasing,” even after Denise confesses that she “eluded any explanations.” Perhaps this is the ultimate response to Debuffet. And if we want to bring up

Would we be more satisfied accepting art on its own emotional terms? That’s a big question too. Because just look at the serious grief Denise offers in response to the news cycle, the ostensible “reality” that she feels compelled to confront. She can’t even name Lynndie England as she takes in the Abu Ghraib photos, but, much as many (including Nik) speculate on Nik’s character, she finds herself fixating on England’s “storm chasing,” even after Denise confesses that she “eluded any explanations.” Perhaps this is the ultimate response to Debuffet. And if we want to bring up  First is the idea of audience, and even that idea, as filtered through Spiotta’s novel, goes off in a number of different directions. There’s young Nik playing and posing to his girlfriend Lisa and Denise, the image Spiotta returns to in a big way at the end of the book (and which led me to a particular conclusion about the book that I’ll get to in a bit). Obviously, there is Nik’s choice to conduct his massive project more or less privately, with Denise as his primary audience, commentator and admirer. There’s Ada and her documentary, wishing to bring her uncle into the light of a greater audience. All have intentions, noble and selfish, thoughtful and venal – and that’s one of the many things that so impressed me about Stone Arabia, which is that it tackles the notion of whether the expression of art is “purer” with a tiny audience while also subverting it. Does art function in a vacuum? Is “selling out” a less worthy or more worthy goal? Spiotta simply presents possibilities here, but it’s up to us, as readers, to come to our own judgments, and then, in reaching them, get hoisted by our own petard because we sought some element of rightness or wrongness here.

First is the idea of audience, and even that idea, as filtered through Spiotta’s novel, goes off in a number of different directions. There’s young Nik playing and posing to his girlfriend Lisa and Denise, the image Spiotta returns to in a big way at the end of the book (and which led me to a particular conclusion about the book that I’ll get to in a bit). Obviously, there is Nik’s choice to conduct his massive project more or less privately, with Denise as his primary audience, commentator and admirer. There’s Ada and her documentary, wishing to bring her uncle into the light of a greater audience. All have intentions, noble and selfish, thoughtful and venal – and that’s one of the many things that so impressed me about Stone Arabia, which is that it tackles the notion of whether the expression of art is “purer” with a tiny audience while also subverting it. Does art function in a vacuum? Is “selling out” a less worthy or more worthy goal? Spiotta simply presents possibilities here, but it’s up to us, as readers, to come to our own judgments, and then, in reaching them, get hoisted by our own petard because we sought some element of rightness or wrongness here. I think Ed and Sarah have done a better job than me of analyzing the many connections in the novel — I didn’t think about Brian Wilson, though I did think of Spiotta’s great Eat The Document often while reading Stone Arabia — but I did form one strong impression that neither Ed nor Sarah focused on. To me, it’s obvious that this is a book about memory. There are five characters in the book: Denise, Nik, their mother, Jay the boyfriend, and Ada. They form a pentagon of attitudes about memory.

I think Ed and Sarah have done a better job than me of analyzing the many connections in the novel — I didn’t think about Brian Wilson, though I did think of Spiotta’s great Eat The Document often while reading Stone Arabia — but I did form one strong impression that neither Ed nor Sarah focused on. To me, it’s obvious that this is a book about memory. There are five characters in the book: Denise, Nik, their mother, Jay the boyfriend, and Ada. They form a pentagon of attitudes about memory. As for Jay, he seemed to me an aside. His twee obsession with Thomas Kinkade kitsch and lukewarm kindness means Jay lacks the capacity to harm Denise. He’s a warm body. Given that all of Denise’s energies are tied up in Nik and her mother (Ada is independent enough that Denise arguably needs Ada more than Ada needs her), she hasn’t room or inclination for anything more in her life.

As for Jay, he seemed to me an aside. His twee obsession with Thomas Kinkade kitsch and lukewarm kindness means Jay lacks the capacity to harm Denise. He’s a warm body. Given that all of Denise’s energies are tied up in Nik and her mother (Ada is independent enough that Denise arguably needs Ada more than Ada needs her), she hasn’t room or inclination for anything more in her life.