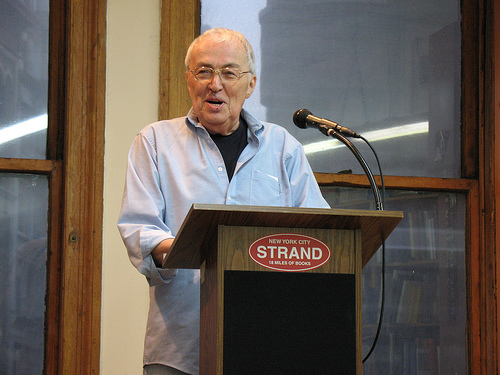

David Markson, who was one of my favorite living writers, has passed away. He was 82.

It’s difficult to convey just how much of a loss this is for American letters, but I’ll do my best as I now fight back tears. Along with John Barth, William Gaddis, and Gilbert Sorrentino, Markson was one of the few writers who proved that experimental writing need not be prescriptive. For Markson, chronicling the consciousness was often tremendous fun: both for him and the reader. And if you were fortuitous enough, it could extend beyond the book. If you lived in New York, Markson could often be located in the Strand’s basement, amicably chattering in good humor with any stranger willing to engage in wanton mischief. The first time I met him, when he was being inducted into the American Academy of Letters, he shouted, “You’re drenched!” in response to my offered hand. This was just after he observed my rain-soaked white shirt. There was the funny five-minute conversation about burlesque and Lili St. Cyr, where we talked about the geometric possibilities of a woman’s derriere. Another run-in where we discussed Ted Williams. On the fourth unexpected collision, he said he would do Bat Segundo if I gave him a call. I neglected to follow up. But maybe this was just as well. For Markson was one of those rare authors who was so great and so thorough that he didn’t really need to offer much more beyond the books. He’d write to you if he liked you. Or if you reminded him of some slinky figure from his carousing days. My girlfriend was the recipient of several flirtatious postcards.

His textual tinkering was never pretentious, never explicitly postmodern, and always good for great laughs. It’s extremely disheartening to know that Markson’s The Last Novel will have the misfortune of living up to its title.

Markson was best known for Wittgenstein’s Mistress, along with a remarkable set of novels beginning with Reader’s Block, whereby random facts about cultural figures were carefully interspersed in short paragraphs, with the “Author” or “Writer” often stepping in with jocular asides. “Writer is almost tempted to quit writing,” begins This is Not a Novel. Was the “Author” Markson himself or some construct? Well, that question was entirely up to the reader.

Roy Campbell was an anti-Semite.

And was one of the few writers or artists aligned with the fascists during the Spanish Civil War.

Like Dali.

Why is Reader always momentarily startled to recall that Keats was a fully licensed surgeon?

Does Protagonist even have a telephone?

Just consider how the associative mind is depicted in these five sentences from Reader’s Block. The Reader is not only invited to confirm these “facts,” but she is very interested in sharing the Author’s surprise about Keats. Was Markson, or the Author, alone in this sentiment? And why should cultural figures be lionized when they were just as fraught with human flaws as anyone else? Markson cemented most of his novels with a very specific consciousness, but he wrote his books in such a way as to include any reader who might be keenly excited about these questions.

The sad irony is that his books never sold very well. Perhaps in passing, Markson’s genius will be rightly recognized. Bestselling authors skimping out on such subtleties have prevaricated about a reader being a friend, but Markson understood that the author-reader relationship worked both ways. If life offers no tidy resolutions, then why should the novel? Does this have to be a depressing prospect? Or can we laugh at such folly along the way? Why can’t the reader share in the predicament? Markson’s books were shared connections between the author and reader, but all participating parties required other texts, other resources, and other souls to make sense of the madness. The other option was Donnean perdition:

Still, what I am finally almost sorry about is that I never did write to Martin Heidegger a second time, to thank him.

Well, and I certainly would have found it agreeable to tell the man how fond I am of his sentence, too, about inconsequential perplexities now and again becoming the fundamental mood of existence.

Unless as I have said it may have been Friedrich Neitsche who wrote that sentence.

Or Soren Kierkegaard.

That last passage comes near the end of Wittgenstein’s Mistress, where the narrator is a woman who believes she’s the last person on earth. But as we start to comprehend the real fiction that she has used to transform her reality, we see that her lonely sentiments matter more than anything else. Text itself is no panacea. Indeed, the very ability to remember text has dwindled without the emotional necessity of other souls. Or as Markson would declare in Vanishing Point, “Do certain people actually remember learning to read?”

Many of Markson’s “facts” were true. They were true in the sense that the tantalizing tidbits originated from some unspecified origin point, but could not be confirmed outside of what was inside the text. Much as an untrue rumor circulates without anybody bothering to consult the originating party. Much as an author would rather talk about his instant passions than the work he has long put away. Because living life is just too damn important.

(Image: adm)

UPDATE: Rather predictably, not a single newspaper or news outlet has thought to report this sad news. But additional remembrances can be found below:

- A.D. Jameson, “Loving David Markson”

- Kimberly Ann Josephine, “Saying Farewell to a Writer and Friend: David Markson”

- Sarah Weinman, “David Markson, R.I.P.”

- HTML Giant comment thread

- The Kenyon Review’s William Walsh posts a remix of Epitaph for a Dead Beat

- Matt Cheney, “David Markson (1927-2010)”

- Scott Bryan Wilson, “David Markson 1927-2010”

- Hallock Hill, “Goodbye, David Markson”

- Some Came Running, “David Markson: Some Notes and Selections”

UPDATE 2: Mainstream outlets are starting to get it together. The Associated Press’s Hillel Italie has the best article so far, getting quotes from Elaine Markson. There’s also a blurb from Los Angeles Times blogger Carolyn Kellogg with a quote from Martin Riker. I’ve also been informed by other editors that more obituaries will be arriving in newspapers over the next few days.

UPDATE 3: New York Times obit.