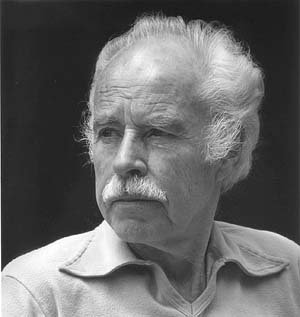

It’s the death day of Wright Morris, who passed away twelve years ago on April 25, 1998. Back in 1910, this famed Nebraskan writer (the second dead Nebraskan writer we’ve celebrated in two days!) had not yet uttered his first word. He then experienced the first death of a loved one. This created a moment for the young Morris to gnaw upon repeatedly in later years. Morris’s mother had died just six days (not even a week!) after young Wright popped out of her womb. In his autobiography, Writing My Life, Wright Morris claimed that, had his mother lived, “my compass would have been set on a different course, and my sails full of more than the winds of fiction.” Well, fellow writers, we must ask ourselves whether Morris’s needle would have been zeroed to an alternative lodestone, had the fates granted him opportunity to mutter “Mama” to the genuine article.

It’s the death day of Wright Morris, who passed away twelve years ago on April 25, 1998. Back in 1910, this famed Nebraskan writer (the second dead Nebraskan writer we’ve celebrated in two days!) had not yet uttered his first word. He then experienced the first death of a loved one. This created a moment for the young Morris to gnaw upon repeatedly in later years. Morris’s mother had died just six days (not even a week!) after young Wright popped out of her womb. In his autobiography, Writing My Life, Wright Morris claimed that, had his mother lived, “my compass would have been set on a different course, and my sails full of more than the winds of fiction.” Well, fellow writers, we must ask ourselves whether Morris’s needle would have been zeroed to an alternative lodestone, had the fates granted him opportunity to mutter “Mama” to the genuine article.

Had Grace Osborn observed her son’s seventh day of life (and many more days beyond), would Morris have become a writer? Grace Osborn was not a deity, but might her mortal sacrifice be perceived as an altogether different form of rest on the seventh day? Would Morris have drifted into another occupation had his mother been hale and hearty? These what-if questions are difficult to address, because all of the involved parties are now dead.

But The Dead Writer’s Almanac’s staff doesn’t view mortality as a liability. Books helped Morris to come to terms with the role that the dead play among the living. In an interview with David Madden, which can be found within the book Conversations with Wright Morris, Morris remarked:

When I began to reread Joyce’s “The Dead,” to see how he achieved — and more successfully than I did — this concept that the dead are always with us, frequently overshadowing the living, I realized that the dead on one level or another constitute our present, whether we will it or not. In certain cultural sensibilities, the dominance of the dead is what constitutes the culture, even to the point of stagnation. Joyce was convinced that the awareness of the presence of the dead with the living is really what makes up civilized behavior and civilized responses. The “presence” of those who are missing, who are physically absent, is the one immortality we can attest to.

And yet a New York Times book reviews search reveals that Wright Morris has not been mentioned once since August 13, 1999. Does the New York Times maintain a policy of not citing a dead writer in its pages after eighteen months of steadfast maggot chewing? If so, this is a great pity. And not just for the maggots. Perhaps the New York Times does not share Morris’s Joycean viewpoint. Perhaps the ostensible paper of record is prejudiced against writers who dare to experiment with photo-text collages. Whatever the Gray Lady’s reasons, we remain quite giddy in celebrating the Cornhusker State’s forgotten literary history two days in a row!

In looking for specific ways in which Morris used the word “dead,” one discovers a concern for capturing “dead” in plainspoken vernacular. “Most of us are dead and gone, think it would be fadin’!” says a character in The Home Place, “Same as me an’ you are fadin’.” And in One Day, Morris writes, “The dead were believed not to matter. Only this immaterial ghost.” On the contrary, Mr. Morris, you matter very much to us! And we hope that our enthusiasm has exhumed you from your needlessly obscure coffin!

Stay writing, don’t die too early, and keep in touch!