Jeff is, quite bravely, quitting smoking. Having started and stopped many times myself and knowing the terrible feelings of nicotine withdrawal and the resultant brain fog, and wanting to see Jeff live on this planet a few extra years, I fully support his decision. Those who would rail against smoking, generally not having smoked themselves, usually have no concept of what quitting smoking entails. But to give you a sense of what it feels like, it involves the entire body screaming at all hours of the day, “I want a cigarette,” and the mind using all of its powers to resist these far from petty impulses. It involves escaping out of routines that were once thought casual but are now discovered to be terribly ingrained and deadly reminders of the previous smoking state (a cigarette after a meal, a cigarette after work, the like) and, if you’re a writer who smokes, it takes considerable time for the brain to adjust to the now nicotine-less environment. Little accident that quitting smoking is often described by methadone patients as “more addictive than heroin.”

Former smokers are often expected to go up against these far from comfy impulses alone, sometimes with the support of friends and family who may not fully comprehend what the smoker is in for. Current society, which is remarkably olfactory and teeth-conscious in the American theatre, would dictate that a certain “tough love” policy should exist. For smokers are often considered to be rapacious addicts who do not even possess beating ventricles. They must, as they snap their head like Gollum at the sight of the Ring, endure other people who smoke cigarettes and the persistent threat of addiction, not permitting themselves to cave into the impulse of “just one.” Even when they have applied patches and nicotine gum.

It seems amusing to me that all of the so-called antismoking PSAs and the like not only fail to understand the problem from the smoker’s perspective, but are punitive in their intent. They give the smoker messages of disapproval, disinterring grainy video images of Yul Brynner telling people not to smoke as he is dying of cancer or, at the more grotesque end of the spectrum, a woman who inserts a cigarette into her tracheotomy opening. I would suggest that a smoker, perhaps silently humiliated by these images, is more inclined to rebel against these disapproving commercials, lighting up rather than staying off the butts, simply because the tone of these commercials transforms smoking into some grisly and over-the-top visual, rather than the commonplace activity that it is. These commercials fail to convey reality to their intended audience. Outside of any bar, you will find habitues firing up their Marlboro Lights with sequential brio. The addiction is treated like a sad, intensely personal thing (it is that and much more) that the recovering smoker can only effect their recovery with a bootstraps mentality that has much in common with the cruel way American government treats the working poor.

Not one of these commercials points out the positive results of not smoking, such as the return of taste and smell after three days. Nor do they note that breathing improves, that sex is better and that a lover’s smell transforms from pleasant to divine. Nor do they point out that the five dollars or so put into cigarettes a day adds up to $1,825/year — truly a colossal savings if the now recovering smoker were to put the money they would spend on cigarettes into a jar. I would suggest that advertisements striking these hopeful notes would perform greater good among the populace at large.

But to get back to Jeff, I’m happy that he’s found another mechanism to contend with the terrible withdrawal he’s no doubt feeling right now. He’s putting together a song list of songs that concern the last cigarette and the like. If you have some ideas, do indeed help the man out.

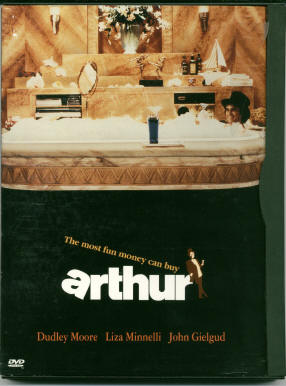

Folks, explain to me the following mystery. And it comes to me because champagne right now is the order of the evening. (Good Christ, is the bottle almost finished?) Sure, Arthur‘s a fine movie. One of the great comedies featuring an alcoholic with a good performance by Dudley Moore. But who was the “genius” who thought that Christopher Cross’ falsetto ballad “Best That You Can Do” was somehow apposite for the film? It can be thoroughly argued that Christopher Cross contributed absolutely nothing to popular music during his career. Even if there were a few misguided souls who thought that Cross’ falsettos projected a certain sensitive male aura, one could argue that Cross’s variety of sensitivity was not only utterly inappropriate, but quite detractive from the plight of the film’s ironic character.

Folks, explain to me the following mystery. And it comes to me because champagne right now is the order of the evening. (Good Christ, is the bottle almost finished?) Sure, Arthur‘s a fine movie. One of the great comedies featuring an alcoholic with a good performance by Dudley Moore. But who was the “genius” who thought that Christopher Cross’ falsetto ballad “Best That You Can Do” was somehow apposite for the film? It can be thoroughly argued that Christopher Cross contributed absolutely nothing to popular music during his career. Even if there were a few misguided souls who thought that Cross’ falsettos projected a certain sensitive male aura, one could argue that Cross’s variety of sensitivity was not only utterly inappropriate, but quite detractive from the plight of the film’s ironic character.