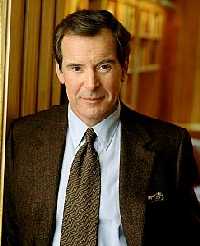

So Peter Jennings is dead. No doubt the paeans will be composed and filed tonight and tomorrow’s newspapers will yield the usual uncritical obits. They’ll tell you how Jennings was the last active member of the Holy Trinity of Brokaw, Jennings and Rather, about how Jennings was the final remnant of a certain time in television journalism (if one doesn’t consider that phrase an oxymoron), and about how Jennings was a decent guy (or at least appeared to be a decent guy).

But for anyone who contemplates shedding a tear or observing a moment of silence, I have to ask an important question: Did Peter Jennings ever ask a tough question in his life? And if he did, did it come during the past twenty years? Because I sure as hell don’t recall Jennings giving us much more than somnolent narration not dissimilar from a half-baked nature program.

But for anyone who contemplates shedding a tear or observing a moment of silence, I have to ask an important question: Did Peter Jennings ever ask a tough question in his life? And if he did, did it come during the past twenty years? Because I sure as hell don’t recall Jennings giving us much more than somnolent narration not dissimilar from a half-baked nature program.

Perhaps I’m fired up right now because I’ve just read this week’s New Yorker and I found myself horrified by Ken Auletta’s article on morning TV talk shows, “The Dawn Patrol” (unavailable online). Aside from that ol’ time sophistication, Auletta’s article is no different from a People Magazine profile in the way that it fawns over its subjects without blinking even a quasi-skeptical eye. Or maybe it might be my outrage after reading Norman Solomon’s new book, War Made Easy, which offers countless examples of how the media has, over the past forty years, repeated the boiler plate of official government memos without deviating, never really daring to doubt or question actions for fear of retaliation, along the lines of what happened to Ray Bonner when he dared to uncover the truth about the El Mozote massacre and found himself pushed out of the New York Times newsroom or when Elizabeth Becker faced resistance when uncovering the truth about Khmer Rouge for the Washington Post and the New York Times (as chronicled in part in Samantha Power’s excellent book, A Problem from Hell).

I recall that my mother liked Peter Jennings a great deal. He was, I suppose, a source of comfort — ironically enough, it took a Canadian to lull Middle America. For her and for many other Americans, Jennings’ soothing voice conveyed an illusory world that was far less problematic than the real one. And it was all because he was an affable, well-liked man who threw softball questions at his subjects more effectively than a batting cage machine.

But I would argue that one can remain reasonably well-liked and maintain a certain credibility. Let’s compare Jennings with, say, Walter Cronkite (incidentally, still quite alive), once considered “the most trusted man in America.” Cronkite had the cojones to declare, “There is no way this war can be justified any longer” after touring Vietnam in 1968. In fact, it was Lyndon B. Johnson who once opined, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.”

Jennings was far from a Cronkite. Or even a Walter Winchell. If anchormen can be likened to a recidivist evolutionary chain extending from Walter Cronkite to Matt Lauer, then Jennings was the missing link that took whatever edge that remained in television-based journalism, suffusing it into a safe and inoffensive approach.

He was a calm, telegenic man who read his words from the TelePrompTer with all the care and duty of a dependable savant being asked to play a recital piece in front of a easily assuaged crowd. He was likable. And in being well-liked, who knows how many viewers he led down the rabbit hole?

I don’t blame Jennings entirely for this. Ultimately, this problem is endemic of the current system. And I’m sorry that he died of cancer. But at a time when only Karl Rove can get the White House press pool to rake Press Secretary Scott McClellan over the coals, at a time in which Americans are so desperate to find someone to trust that they turn to a comedian like Jon Stewart to get their news, and at a time when an anchor’s credentials are judged not by journalistic chops, but by how well-liked, coiffed and curvy they are, it seems to me a disgrace that we prefer to take solace in those who are well-liked rather than the journalists who dare to provoke or tell the truth. In short, celebrating Jennings is, in a strange way, ignoring those who dare to do the work of a journalist, television ratings and focus groups be damned.