You can’t find a thermometer anywhere. It took me three days to get two thermometers and I’m usually very resourceful. I mean, if I can’t find one fast, nobody can. Pharmacies and the stores are all cleaned out. If you try ordering a thermometer from Amazon, you’ll end up waiting a month for it to be delivered. And right now, as the Coronavirus escalates in the States, we really need a way to be able to detect it as early as possible. The early signs involve fever. And with COVID testing proving to be outside the grasp of anybody other than the affluent, the only real way for us to know if any of us may have it is to check our temperature. But if we don’t have the tools, then how can we know?

Enter the temperature stand, an idea inspired by Lucy’s lemonade stand in Charles Schultz’s Peanuts. Schultz had the right conceptual idea. What if a lemonade stand, which serves the community, were altered for medical purposes? What if we set up a network of temperature stands around the nation? Free temperature tests. No questions asked. Along with a few jokes and friendly banter just to make people feel safer and happier. The temple thermometer I have takes just three seconds to register that my body is running normally at 98.4. What if we enlisted volunteers to take the temperature of everyone in the neighborhood?

I really want to set up a temperature stand. I left the house today to talk with a pharmacy in my neighborhood about setting one up in front of their store. The pharmacy advised against it. So did a local cop. Why? Because there are now stringent edicts in place, along with a heavy police presence (many of the cops in my hood are wearing facemasks). So I can’t do this — even though I very much want to help people in my neighborhood. I’ve already started taking people’s temperature on the sly, dabbing my thermometer probe with a cotton ball soaked in alcohol immediately after. A guy at the bodega who comes into contact with perhaps a hundred people each day, grateful to know that he didn’t have a fever, offered me a free six pack of beer for doing him a solid. I politely declined. That’s not the way a temperature stand should work. Taking people’s temperature really should be free and ubiquitous. Think of this as a kind of healthcare volunteer squad, united by a common code rather than a common cold. It also feels incredibly strange to be an outlaw in the interest of public health. But, hey, if heading out into the city with a digital thermometer and a balacava and a secret name in the dead of night is the only way for me to help people, I’ll do it.

I’d set up a temperature stand it in a heartbeat, but I now know that I would be immediately shut down. Honestly, temperature stands make total sense. We need to be able to find and quarantine anyone who has a fever so that they don’t spread the virus.

I’m writing this quick dispatch to get this idea out there. To see if we can make something like this instantly happen.

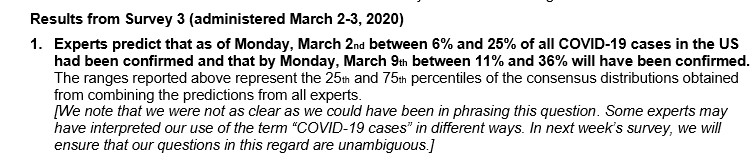

Expert epidemiologists have informed us that the reported number of Coronavirus cases represents only a fraction of the total — perhaps as little as 13% of all cases. So it’s vital for us to have ways to collect data.

But if we have a way to take people’s temperatures, then we would stand a stronger chance of cutting down the number of cases. We’ll also have a way of flattening the curve while bringing our communities together.

So who’s with me? If we can’t keep a temperature stand in regular operation, then let us become masked avengers of the night — with a digital thermometer becoming the most valuable tool on our Batman utility belt!

I can tell you this much. I’m not leaving the house again without my thermometer. Not for me, but for other people. “I have a thermometer. Would you like me to take your temperature?” will now be added to my usual “Hello, how are you doing?” as long as we’re dealing with this pandemic. If you run into me, I’m more than happy to take your temperature.